Guatemala

Quirigua

Similar structural three-stone alignments to those found at Palenque, Tikal and Teotihuacan also occur at Quirigua. Stela Triad 18 to 20 reflects similar size discrepancies of its monuments, moreover, placing the largest to be centrally-flanked by the two smaller ones. This alignment pattern is also evident in the three-stone monument group at Quirigua including Stela A, Zoomorph B and Stela C [1], which also exhibits the same proportional ‘measuring out’ that is evident at Palenque, Chichen Itza and Teotihuacan. At Quirigua, moving from Stela A, to Zoomorph B (displaying earth-turtle themes, appropriately placed close to the ground) we arrive at Stela C, which includes a hieroglyphic record of the beginnings of creation, a ‘birth’ event [2].

[2] Quirigua Stela C, east side text, showing k’al glyph ‘to bind’ or ‘tie’. The text is important in its recording of the Maya creation account.

Another three-stone complex at Quirigua is formed by Zoomorph P and O (and their associated altars) and the Acropolis located behind them. Zoomorph P and associated Altar P’ and Zoomorph O and associated Altar O’ are surrounded by trenches. During the rains, the trenches fill with water causing the gigantic stones to seemingly float on their own watery reflections on the horizontal waters supporting the world: perhaps seen as forming the primordial waters of the world and ‘water stone’ throne. The cyclical motion of flowing water is expressed by the different roles of the two Time Gods, K’awiil symbolising birth from water and Chaahk’s descent into water equated with death and sacrificial blood offerings feeding the fertility of its waters (also descending rain, see Maya Gods of Time). Quirigua was particularly bound to the water cycle, built on a floodplain where the rains could cause considerable damage (for example, in the Classic period; see Sharer 1988), while, simultaneously, delivering fertile soils increasing crop production. Consequently, orchestration of the symbolism displayed by these Quirigua monuments seems to recall the life energy signalled by the arrival of the winds promising rain, felt throughout Central America, and links these stones to a recurring ‘timed’ event.

J_Quirigua 1. East and West Side details carved on the surface of Quirigua Zoomorph P [3], that, as the viewer moves around the monument (and on inversion of the East Side head), visualise the young man’s exhalation of breath by animating the flowery breath symbol placed immediately before his nose and mouth to rise and fall. Simultaneously, the reptile’s elaborate maw, from which the head emerges, unfurls as it swells in size with the intake of the young man’s breath, seemingly inflating. Note also the movement in the man’s hair, flying upwards and forward. The solid stone of the large monument is thus contrasted with the unseen motion of time (see Maya Gods of Time). Animation extracted and adapted from Maudslay 1889-1902, vol. II, plate 61.

J_Quirigua 2. East and West Side details surrounding the upper portion of additional large large eyes carved on the surface of Quirigua Zoomorph P [3], that, as the viewer moves around the monument, animate a K’awiil figure to spill the contents from a bowl he turns upside down. Liquid scrolls marked with ‘precious’ jade ovals flow from the bowl that doubles as a large glyph; the stream carries a ‘precious’ k’an sign in its flow, likely implying sought-after rain falling from the sky. At the same time, K’awiil opens his long-snouted maw. Once again, the solid stone mass of Zoomorph P is compared with the unseen motion of time (see Maya Gods of Time). Animation extracted and adapted from Maudslay 1889-1902, vol. II, plate 60.

J_Quirigua 3. East and West Side details surrounding the lower part of additional large large eyes carved on the surface of Quirigua Zoomorph P [3], that, as the viewer moves around the large monument, animate a further K’awiil to twist and writhe about a scroll that contains his body. In the first instance, K’awiil holds up a large glyph, likely the negative marker mi signifying ‘nothing’ or ‘zero’ and is also surrounded by akb’al signs meaning ‘dark’; then, he stretches to push his head and one of his arms outside the scroll ‘frame’ and widely opens his long snout from which gushes a stream marked with lem logograms meaning ‘to shine’, ‘to flash’ and possibly also ‘lightening bolt’, along with further glyphs. A very tentative interpretation of this animation might imply K’awiil’s movements causing a lighting strike that issues from his mouth and illuminates the darkness that came before. As in the previous two examples, K’awiil’s movements are contrasted with the solid stone carving of Zoomorph P, aimed by the ancient Maya at comparing the unseen motion of time with the stability of unwavering, motionless stone (see Maya Gods of Time). Animation extracted and adapted from Maudslay 1889-1902, vol. II, plate 60.

J_Quirigua 4. Details carved either side of the seated figure at the front of Quirigua Zoomorph P [3], that, as the viewer moves around the large monument, animate a further K’awiil to clutch a receptacle doubling as a large glyph against his body; probable large liquid scrolls flow from the receptacle (see above J_Quirigua 2). Simultaneously, K’awiil moves his legs and opens his mouth. As shown in the previous three examples, K’awiil’s movements are compared to the solid stone mass Zoomorph P is carved into, thus juxtaposing the unseen motion of time with the stability of immobile stone (see Maya Gods of Time). Animation extracted and adapted from Maudslay 1889-1902, vol. II, plate 64.

Quirigua Stela D, west side hieroglyphic text, showing glyphs 4-5.

As the viewer scrolls down the hieroglyphic column to read its text, the fanged deity to the left, clutching a reptilian supernatural beast, raises himself from a prone to an upright, sitting position.

It is quite possible that the creature the deity holds, simultaneously, transforms, its beaked maw still visible and now turned to the viewer’s left.

Drawings and animation above extracted and adapted from Maudslay 1889-1902, vol. II, plate 26.

J_Quirigua 5

North sides of Quirigua Stelae C (left) and A (right), moving west to east, animate movement and transformation.

As the viewer moves from west to east, the carved figure alternates the raising of his heels in dance and moves his left hand up across his large chest plate displaying a prominent KAN ‘sky’ logograph.

Simultaneously, his initially human-looking hands and feet transform into clawed paws.

Animation extracted and adapted from Maudslay 1889-1902, vol. II, plates 8 (Stela A) and 20 (Stela C).

Naranjo

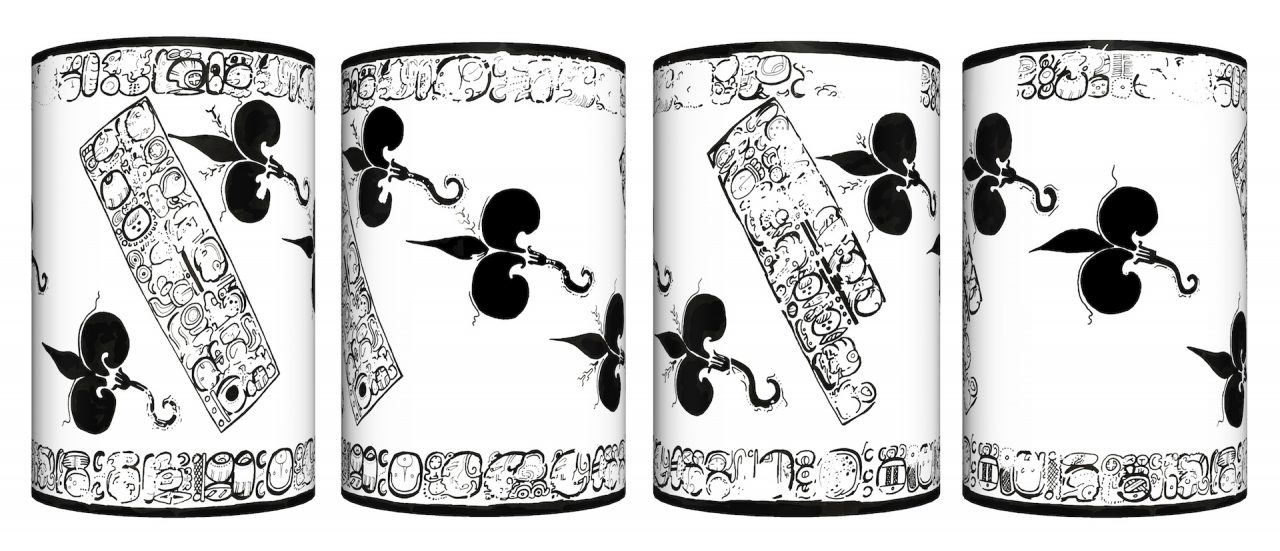

A series of beautiful polychrome cylinder vases originate from Naranjo. They were painted by the royal artist Aj Maxam, whose name we know from him signing his pieces by including his title in the hieroglyphic text bands (PSS [Primary Standard Sequence]) running around the vase rims.

The regular compositional placement of ‘three’ upon circular shapes, such as the positioning of ceramic tripod feet or handles, was almost certainly achieved by stretching a cord across the diameter of the ceramic vessel. When tripled, the cord stretches almost exactly around the circumferences of the vessels. The phenomenon relates to the mathematical concept of pi (π), where the circumference divided by the diameter of a circle is 3.1415 (we have rounded this infinite number to four decimal places).

It is highly likely that ancient Maya artists applied this law to achieve the correct spacing of scenes encircling ceramics or placement of tripod supports and handles. For example, it is almost certain that the royal artist Aj Maxam ‘measured out’ the three scenes of his Dancing Maize God Vase using a basic paper template before commencing work [1]. Otherwise, painting the three scenes with such unparalleled exactness around the circular exterior of the tall vase would have been virtually impossible. Subsequently, by altering chosen parts of the template, Aj Maxam was able to convey animation, breathing life into his work. Similarly, stonemasons and artists would have planned and measured out triptych lintel, stela and altar sequences.

Ceramics

J_Naranjo 1

Details of a Late Classic vase currently known as the Vase of the Seven Gods, from the vicinity of Naranjo, forming an animated account of creation.

The artist of the vase, Aj Maxam, portrays the performance of two deities, GI and GIII, as they manifest from primordial darkness. Aj Maxam utilised the Maya visual convention of ‘three’ to animate the scene. To understand the becoming within the scene, we must see the unseen by focusing on the elements that change in each sequential depiction. For example, looking at the varied sweeping motion of the two deities’ hand gestures, we notice how the upper deity moves his left hand from resting on his right shoulder in the first depiction, to his mid-upper right arm in the second, before coming to rest it on the elbow of his right arm. In the third visualisation, his right arm reaches out, fully extended, to place his hand upon the stone before him. See Maya Gods of Time for a thorough discussion of the symbolism displayed on this vase.

Animations extracted and adapted from Robicsek and Hales 1981:244, fig. 87a.

J_Naranjo 2

Inverted details of a Classic period Maya vase painted by the artist Aj Maxam animating triadic bird-flower fusion groups to ‘fly’ up and across the surface of the vase; similar bird-flowers occur on polychrome vessels also elsewhere.

Animation extracted and adapted from Reents-Budet 1994:159, fig. 4.50.

J_Naranjo 3

Classic period Maya vase painted by the artist Aj Maxam displaying triadic flower groups that are animated on turning of the vase to ‘fly’ across its surface; elsewhere, similar flowers metamorphose into flower-bird fusions (see above).

Animation extracted and adapted from Reents-Budet 1994:61, fig. 2.30.

Chama

Ceramics

J_Chama 1. Details of a Late Classic polychrome vase painted in the Chama style; the original vase shows the distinctive chevron band framing a palace scene at top and bottom. The geometric chevron band encourages rotation of the vessel following the ‘arrow’ points in a clock-wise direction, which animates the attendant to bow before the enthroned ruler.

Accessed at http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/31866, June 2019. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; gift of Charles and Valerie Diker, 1999.

J_Chama 2

Classic period polychrome vase animating, when rotated, a seated jaguar beast with deer antlers to straighten up and change its hand positions. Simultaneously, the beast’s head shrinks as it exhales a large, red speech or breath scroll, as if squeezed of all its air, and a big red bifurcated scroll appears attached to the end of its tail; a likely speech scroll, it connects to the written words depicted on the original vase running in a glyph band around the vase rim, possibly articulating the beast’s utterings.

A three-dot cluster marking the beast’s jaguar ear reminds the viewer of the Maya notion of three-part time driving the beast’s physical and oral motion.

A geometric chevron band framing the scene at top and bottom on the original vase, typical of Chama vessels, encourages rotation of the vessel following the ‘arrow’ points in a clock-wise direction.

Animation extracted and adapted from Kerr 2000:395, file no. 3231.

Tikal

At Tikal, the Grand Plaza once accommodated a three-stone complex that must have been one of the most impressive examples of triadic stone structures dedicated to time in the Maya world. Unfortunately, however, part of the largest ‘stone’, that is, the entire North Acropolis, was destroyed when archaeologists dug too many trenches into the structure causing a partial collapse (see Coe 1965, fig. on pp. 28-29). The North Acropolis runs along the entire northern edge of the Great Plaza, with Temple I at its eastern and Temple II at its western sides. Together, these structures form a three-part stone complex, with the largest, the North Acropolis, formed into a series of edifices built to resemble a complex hive of vaulted structures, one atop another, like a honeycomb. The constant rebuilding of the structures, carried on for over a thousand years, built and rebuilt atop a single platform, is tied to the symbolic role of the structure, as the central and largest time stone, tied to growth. Moreover, the North Acropolis once supported three temples rising like towers, mimicking the three ‘Jester’ elements protruding from the headdress of the deity associated with the largest time ‘stone’, Ux Yop Huun, to literally showcase the ‘growth’ of the kingdom as it developed over time.

The following link takes you to the website www.artsandculture.google.com, a collaboration of the British Museum and Google Art & Culture, that provides a virtual tour of Tikal, starting from atop this large three-stone-complex.

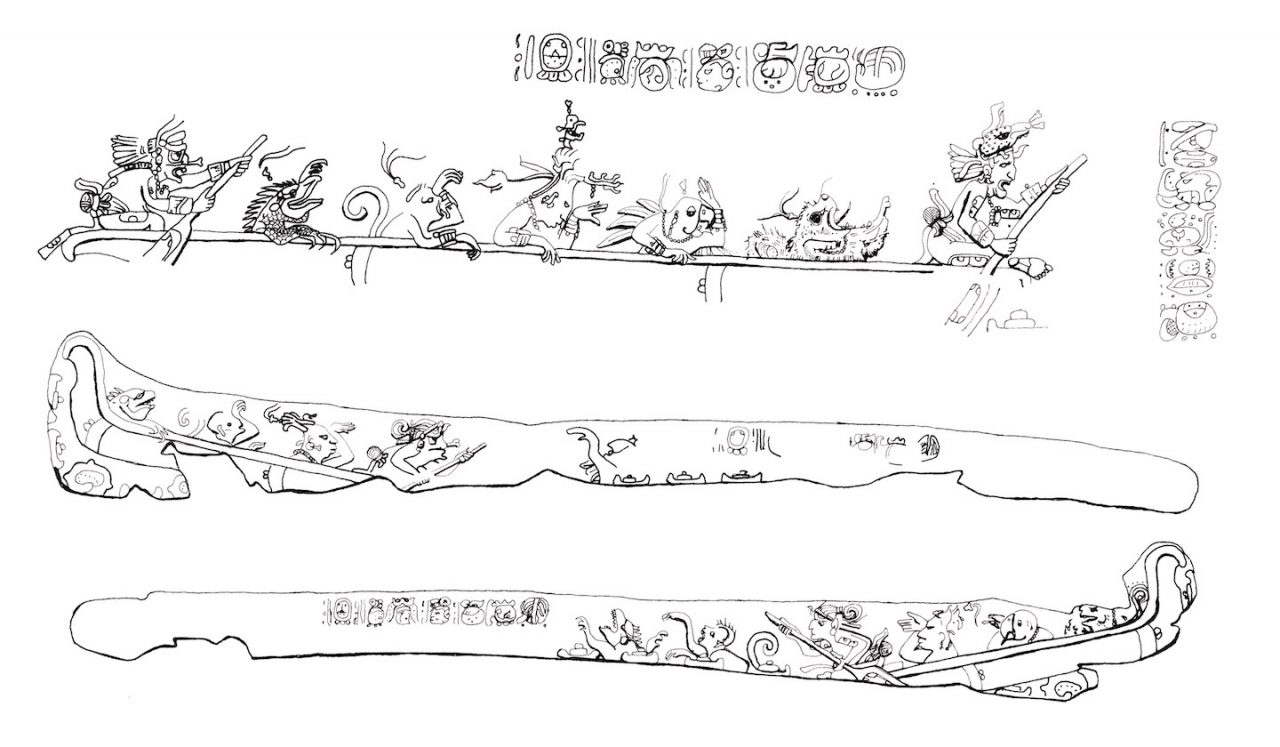

Unfortunately, whatever animations these temples once housed have now largely been lost. Topping the stairs, the temple sanctuaries once boasted magnificent carved wooden lintels; considering patterns elsewhere, it is highly likely that walking between and ascending and descending the stairs of these three Tikal temples would have activated an animation recorded across these lintels. The lintels have largely perished as they were made of wood; the fragmentary remains of Lintel 3, which once spanned the doorway of the rear chamber of Temple IV, was moved to the Museum of Völkerkunde in Basel, Switzerland, in the last century.

Ceramics

J_Tikal 1

Classic Maya polychrome bowl from Tikal animating, on rotation, an aqueous K’awiil head and the fish that feeds on its waterlily blossom to swell greatly in size.

Animation extracted and adapted from Kerr 1994:553, file no. 4562

J_Tikal 2

Late Classic polychrome vase from Tikal animating an elite figure turning in dance to kneel before an enthroned ruler. The vase depicts two dancers: one, holding a large white bowl, stands to the right of the enthroned ruler (vase view 1 above), and turns his back on an individual playing a large drum. The drummer is closely observed by the first depiction of the second dancer (vase view 2 above) represented three times. This dancer’s second depiction shows him turning (view 3), then kneeling (view 4) before the lord (views 5 and 6), all the while slightly shifting the position of his arms.

Displayed in the Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología, Guatemala City.

Uaxactun

Uaxactun boasts a solar observatory said to be the most accurate in the Maya world (Early Classic Group E [1]); it allowed the Maya to chart the movement of the sun in relation to the horizon. The interaction between the sun and the horizon was observed through the use of three points or ‘markers’ (indicated by the white arrows in the photo); three stone structures that linked three (stone structures) to time through the movement of the sun and the temporal rhythm of the year. The giant time-keeping ‘stones’ reveal how the Maya saw time to be responsible for moving the sun between these three points and its three-part structure. The same three-part rhythm structured their day, year and Maya life ‘time’ metaphors, such as the men who worked the fields, toiling beneath the sun (see Maya Gods of Time).

Ceramics

[1] Incised vase from the vicinity of Uaxactun. Its three vertically-stacked oval cartouches display the profile of a monkey, revealing slight variation to convey animation; for example, the hair lines on the viewer’s right increase from one, to two, to three (highlighted blue). Uaxactun private collection.

Uxmal

The Maya notion of ‘time as three’ and its construction from three parts was clearly incorporated into the name of Uxmal, literally translating as ‘Three-Times Built’, or, as we suggest, ‘Time Built’, related to the many triple-stacked gods adorning the building façades at the site [1].

The enclosed stone courtyards of Uxmal very likely formed symbolic and echoic spaces. Standing within the courtyard and clapping creates reverberating echoes, directly relating the clapping noise to time and the speed at which sound travels, rebounding from the surrounding solid stone walls. We believe that these echoes, as repetitions of sound, connect to the repeated deity heads that decorate the structure walls throughout the site [2]. The carved heads relate to the Gods of Time and to sound, displaying upturned noses forming an identifying feature of both Chaahk and K’awiil. Rhythmically spread, these deities symbolically echo each other diagonally across the structure walls, seemingly bouncing off opposing walls.

San Bartolo

Murals

J_San Bartolo 2

Details of the Late Preclassic San Bartolo North Wall mural animating the carrying of fire bundles. The three figures with black body paint, when considered together, animate walking in ‘three’ from the viewer’s right to left; initially they support burning bundles on their heads. Masked, these figures approach a standing deity at the far left, where the third kneels to support a gourd-like plant on his head. He is now unmasked and turns to converse with the deity standing before him. Note the three weaver birds surrounding a drop-shaped nest, at the viewer’s far left, animating the dynamic flight of a single bird in three steps and also circular spinning.

Drawing and animation extracted and adapted from a watercolour by Hirst (2003) displayed in the Museo Popol Vuh, Guatemala City.

Tiquisate

Ceramics

J_Tiquisate 1

Incised, black cylinder vase which, on rotation in the viewer’s hands, animates a dancing monkey to interlock its raised arms above its head.

Animation extracted and adapted from Reents-Budet 1994:240, fig. 5.5.

Ucanal

Ceramics

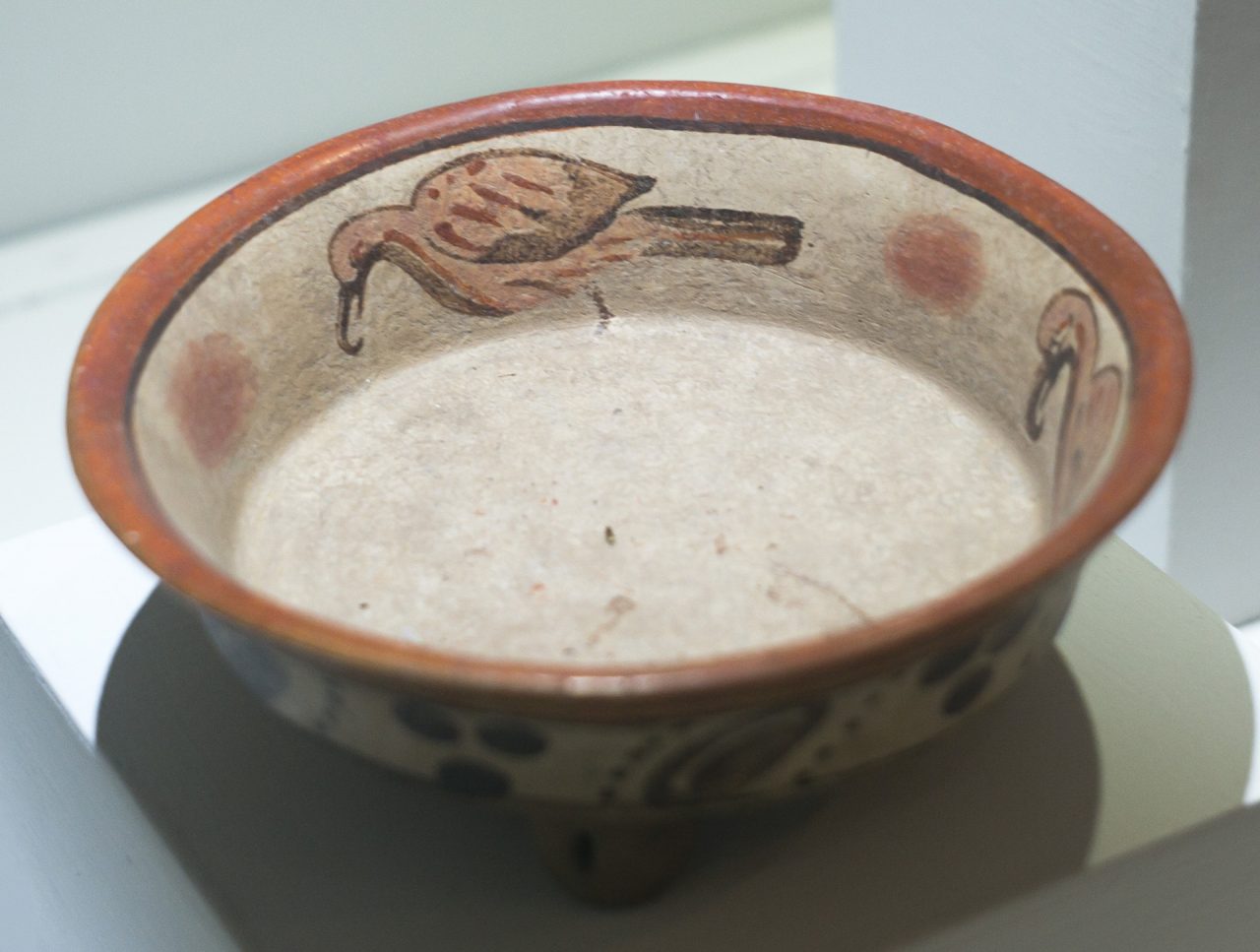

J_Ucanal 1

Details of a Classic period Holmul-style bird vase from Ucanal depicting a cormorant opening its beak in three stages to animate its squawk. The cormorant hovers above stacked water symbols surrounding a large shell (depicted on the original vase), which pinpoint its watery location.

Animation extracted and adapted from Reents-Budet 1993:246, fig. 6.13.

Ixtuts

Ceramics

[1] Late Classic vase from Ixtuts showing two individuals in a cacao-drinking ceremony. When the vase is rotated in the viewer’s hands, two scenes painted on its surface articulate the motion involved in the figures preparing the beverage; in the second scene, the cacao-frothing stick has been placed in the tall vase, causing the figure on the right to open his mouth in anticipation of his imminent tasting of the drink. Displayed in the Museo Regional del Sureste de Petén, Dolores, Guatemala.

Xultun

Ceramics

J_Xultun 1

Classic period polychrome Maya vase, which on turning, animates two humanoid insects to fly, one above the other. The creatures exhibit skeletal-looking heads, human hands and feet, and large insect wings and abdomens; they wear eye-ball necklaces, possibly also marking their heads and wings, and emit large air scrolls from their mouths and behinds, likely foul breath and flatulence.

Animation extracted and adapted from Kerr 2000:1012, file no. 8007.