Mexico

Bonampak

J_Bonampak 1. The figures shaking the large rattles have been highlighted in this animation to visualise how, even though the musicians seem to represent different individuals (indicated by their differing facial features and loin cloths), the Maya artist(s) purposefully staged the fluid motion involved in shaking the instrument with each musician presented like a ‘frame’ or ‘still’ of a movie, in combination describing the shaking of the rattle; as such, the motion follows the progression of time and accompanies the musicians’ ‘passage’ along the wall. Miller and Brittenham (2013:117) first noted how these five Bonampak rattle players complete the single fluid action of shaking a pair of rattles.

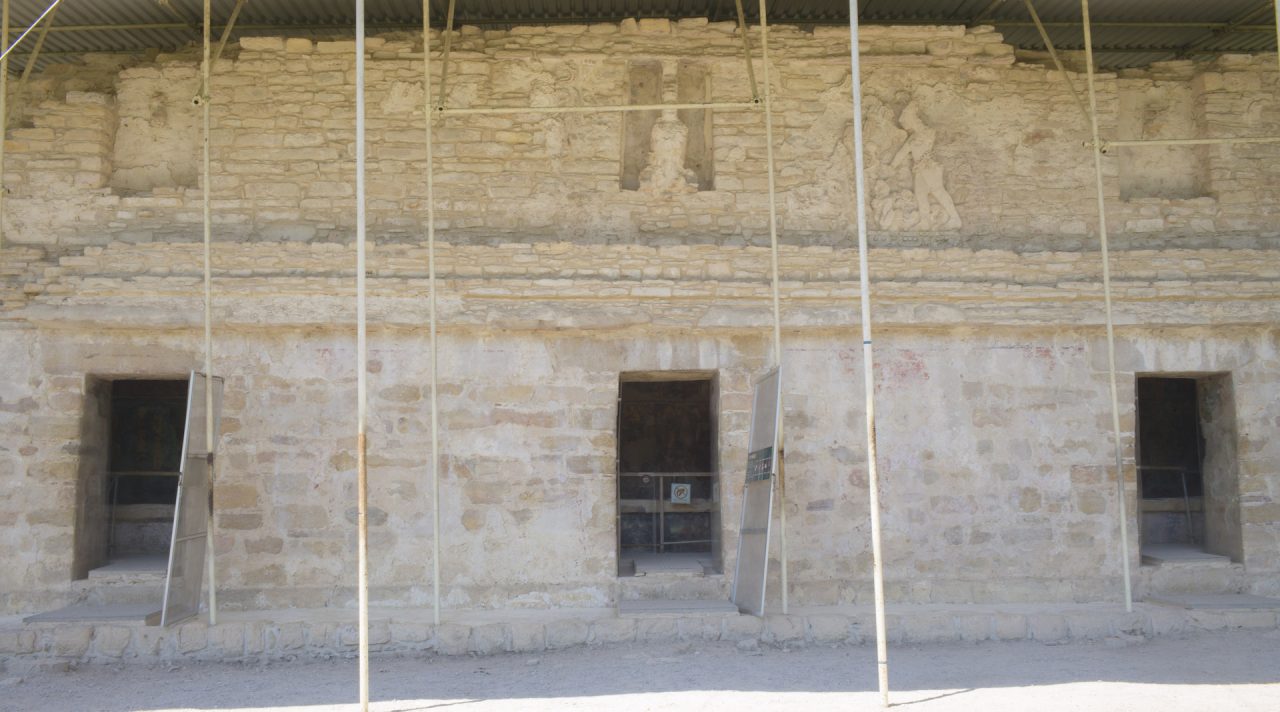

The Late Classic Bonampak murals are painted on the interior walls of three small rooms occupying a single structure. Each doorway is supported by a carved stone lintel that requires the motion of the viewer between the three door lintels to activate, in ‘three’, their animated content; the three lintels animate a lord spearing a captive (see J_Bonampak 2). Change between the first and second lintels is subtle, then greater in its jump from the second to third lintels; it represents a temporal-spacing pattern frequently repeated in Maya animations (see Maya Gods of Time). Inside the building the murals themselves also include many examples of animation; for example, the fall of a vanquished warrior collapsing to the ground (see J_Bonampak 3), the pained writhing of a captive following fingernail extraction (see J_Bonampak 6) and a lord shown dressing in three steps (see J_Bonampak 7).

The motion required to view the entire Bonampak mural sequence is key to their understanding and, moreover, reflects the way the Maya perceived time. In order to engage with each of the small rooms, the viewer must repeatedly walk to enter, then halt (to look up at the lintels), before proceeding into each room and spinning about their own axis in order to absorb the entirety of each mural sequence; this process is repeated three times. We believe that the variation of pacing, halting and spinning involved in surveying the artwork relates to the paradox of time, where perceived static moments are juxtaposed with flowing and spinning motion. Accordingly, the repeated act of standing (in three) juxtaposes these static or stable moments with the repetitive act of turning (in three), representing the motion driving cyclical change.

The murals – and their relation to the motion of the viewer and time – are discussed in greater detail in our paper:

Lintels

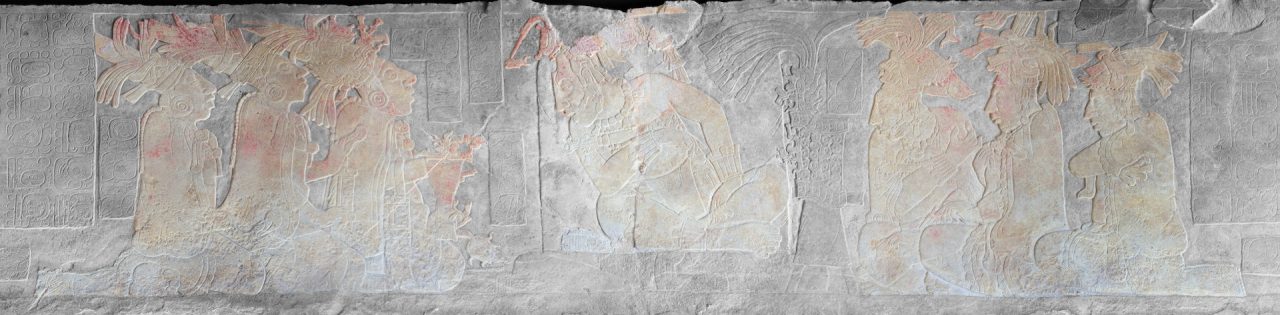

J_Bonampak 1

Details of Classic period Bonampak Lintels 1 to 3, carved and painted on their underside and supporting the three doorways leading into Structure 1 shown in the image above (left to right). To absorb the sum of the artwork the viewer must walk between the three lintels. Pieced together, the sequence animates the spearing of a captive grasped by his hair.

Stelae

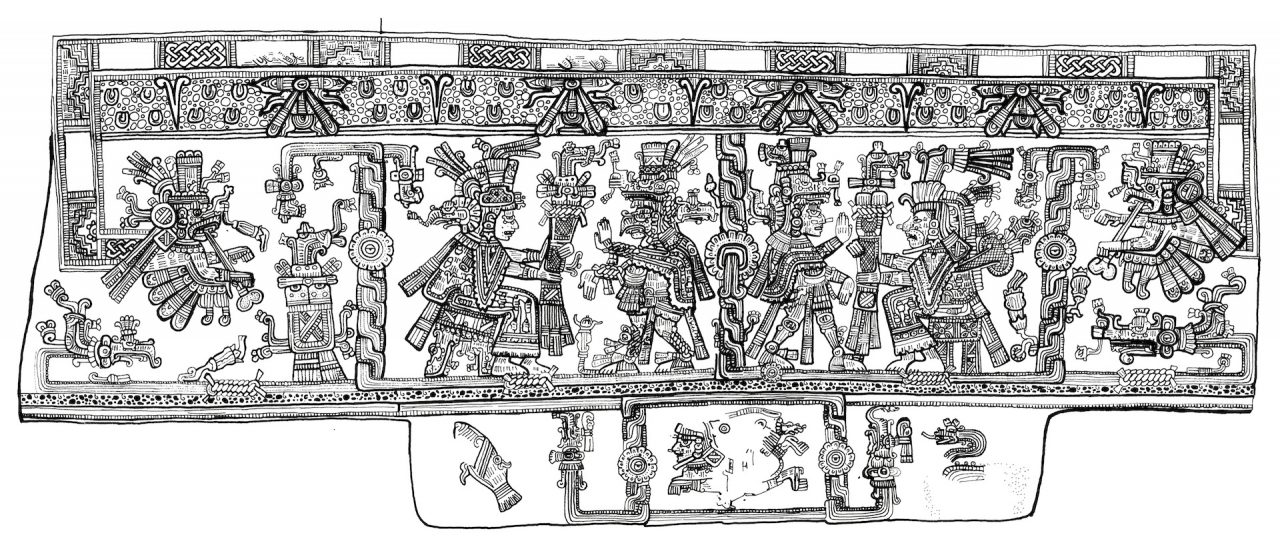

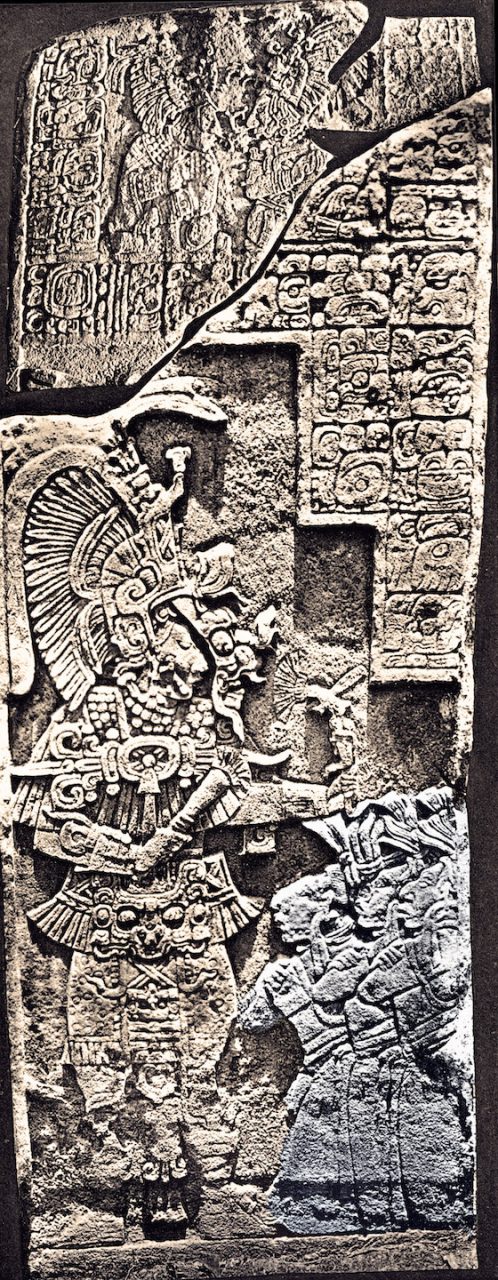

[3] Late Classic Bonampak Stela 2 showing Yajaw Chan Muwaahn II getting married (Bíró 2011); while the two highlighted ladies are named as different individuals, they complete a single action involving the raising of a bowl containing blootletting paraphernalia.

Murals

Room 1

J_Bonampak 2

Late Classic Bonampak Structure 1, Room 1, north wall mural details animating the motion of a trumpet player to shift his hands holding the instrument closer together.

As is frequently the case in the Bonampak murals, while the animated action might be performed by different persons (making up the row of parading musicians), their individual movements complete, or describe, a single movement; for example, involving holding and playing a trumpet, or shaking a pair of rattles (see J_Bonampak 1 above).

Line drawing animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:79, fig. 137.

J_Bonampak 3

Late Classic Bonampak Structure 1, Room 1, east wall mural details animating the movement of large fans cooling dignitaries watching a royal dance.

Even though the fans represent two separate items, one orange, the other yellow, furthermore, held by different individuals, the artist(s) chose to show the different positions of the fans in the air to portray their fanning motion made possible by the progression of time; and the viewer moving their eyes along the mural sequence.

J_Bonampak 4

Late Classic Bonampak Structure 1, Room 1, east wall mural details animating a musician beating his turtle-shell drum with a deer antler as the viewer follows his progression along the mural wall.

J_Bonampak 5. This Bonampak wall animates a lord to dress in three steps. The lord’s minimal movement, merely attending to the tying of his own wrist bands, accentuates the busy animation of his attendants, twirling around his person, dancing to tend all his robing needs.

Movement is initiated by the attendants preparing the lord’s backrest, first by the left-hand figure advancing up a step immediately behind the lord; he simultaneously sharply twists his head back down to look, via the lord, to the attendant kneeling with his back turned towards the lord and also holding a backrest. The scene continues with the lord’s second depiction gesturing to a servant, who proceeds to tie the wristband in the lord’s frontal depiction. Finally, the momentum driving the dressing scene is completed when the lord is fully dressed with his magnificent backrest feathers reaching high into the sky to connect with the room vault above.

Late Classic Bonampak mural, Structure 1, Room 1, north wall details. Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:78, fig. 133.

J_Bonampak 6

Animation of a ball player turning while he waits to play. Bonampak East Room 1, south and east wall mural details.

Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:113, fig. 212 (HFs 65-66).

J_Bonampak 7

Animation of a messenger’s hand gesture. Bonampak East Room 1, east wall mural details.

Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:113, fig. 212 (HFs 1-2-3).

J_Bonampak 8-9. Animation of a royal messenger turning from the east to south walls and animation of a high-societal hand gesture. Bonampak East Room 1, south wall mural details.

Animations extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:113, fig. 212 (HFs 4-5 and 6-7).

J_Bonampak 10

Animation of a high-societal hand gesture. Bonampak East Room 1, south wall mural details.

Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:113, fig. 212 (HFs 10-11).

J_Bonampak 11

Animation of a high-societal hand gesture. Bonampak East Room 1, south wall mural details.

Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:113, fig. 212 (HFs 12-13).

J_Bonampak 12

Animation of a high-societal hand gesture. Bonampak East Room 1, south wall mural details.

Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:113, fig. 212 (HFs 67-68-69).

J_Bonampak 13. Animation of an elegant courtier turning to speak to the courtier behind him. Bonampak East Room 1, north wall, west-side animation.

Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:80, fig. 142 (HFs 75-76-77).

J_Bonampak 14

Animation of the enactment of the possible transformation of a human into a crocodilian beast to mark the moment of creation signalled by the deity impersonators’ exchange of corn (standing immediately above, HFs 45-46), which represents the seed for future rebirth. The possible transformation is suggested by features of the first human actor (HF 47) carried over into that of the beast (HF 48), including the bulbous green collar edge repeated by the crocodile’s scales, waterlilies growing from their headdresses and the humanoid limbs of crocodile.

Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:79, fig. 137 (HFs 48-49).

J_Bonampak 15. Two triptych animations are reflected about a mirror held up by a kneeling attendant on the north wall mural between the lord’s dressing scene and standing dignitaries. Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:126, fig. 236 (HFs 75-76-6 and 23-25-27).

Room 2

J_Bonampak 16

Late Classic Bonampak Structure 1, Room 2 mural details, north wall, southwest corner. On passing, a warrior is animated to fall to the ground within a battle scene; note the figure’s increasing state of undress, emphasising defeat and progressive descent.

J_Bonampak 17

The line drawings of the corner details of Bonampak Room 2, where the east and south walls meet, make clearer the animation of a trumpet player’s motion, raising and lowering the long horn he blows.

Late Classic Bonampak Structure 1, Room 2 details (HFs 7 and 35).

J_Bonampak 18

At the point of capture, Yajaw Chan Muwaan violently jerks the victim by the hair. Simultaneously, his jaguar-head headdress swells to reflect his increased power. Bonampak Central Room 2, south wall mural details.

Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:94, fig. 172 (HFs 54-55).

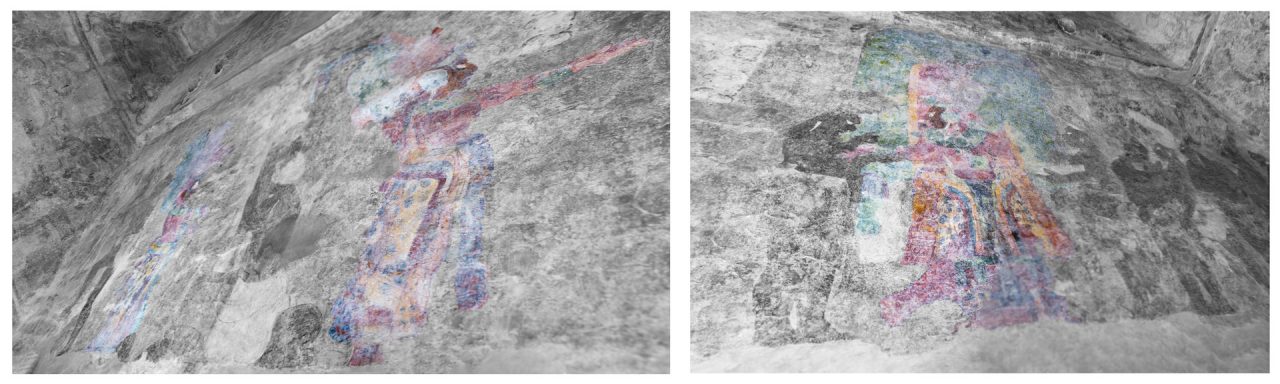

J_Bonampak 19. Late Classic Bonampak Structure 1, Room 2, north wall mural details animating the blood dripping from a captive’s fingers, whose nails have been pulled off as a form of torture.

The sequence forms part of a larger scene that depicts war captives presented to the ruler Yajaw Chan Muwaan (on the right), who stands centrally on a large temple summit surrounded by royalty, also shown watching from the lower tiers [see photo above; Maya Gods of Time, fig. 3.23]. The three middle temple tiers display nine captives, stripped of their regalia and power insignia, whose movements, in combination, complete the animated sequence of what would have befallen each of the unfortunate individuals, and what is partly shown in the above animation; that is, to end up sprawled on the temple steps beneath the lord’s feet, after initial fingernail removal. Their horror is plainly visible on their contorted faces.

What is important is to read what lies between each depiction, the unseen, similar to the workings of the Maya literary devise called a merismus, where two specific words are linked to refer to a third and broader concept; for example, in the Popol Vuh ‘deer-birds’ refers to all wild animals (see Christenson 2007:48), while ‘thunder-bolt’ forms a poetic reference to what separates and yet binds the two words, namely ‘time’ (Maya Gods of Time, p.116). In the Bonampak captive scene, read as a visual equivalent to a Maya literary merismus, the depictions juxtapose the victims’ capture and torture to refer to the third broader concept of death, depicted centrally in the scene by the dead captive sprawled over several of the temple stairs.

To read the scene the viewer is required to move across the room and sweep their eyes along the mural wall to take in the animation, partly played out in the animation above. In this manner, it is the viewer’s own movement which animates the sequence and brings the torture scene to life, thus bringing their own experience of the passing of time to the event.

Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:103, fig. 190.

J_Bonampak 21

Animation of a dignitary changing the position of his hands on his spear. Bonampak Central Room 2, north wall mural details.

Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:75, fig. 125 (HFs 89-90).

J_Bonampak 22

Animation of a dignitary lowering his staff or torch. Bonampak Central Room 2, north wall mural details.

Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:75, fig. 125 (HFs 92-93).

J_Bonampak 23

Animation of a dignitary changing how he grasps his spear. Bonampak Central Room 2, north wall mural details.

Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:103, fig. 190 (HFs 115-116).

J_Bonampak 24

Animation of a dignitary changing how he grasps his spear. Bonampak Central Room 2, north wall mural details.

Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:103, fig. 190 (HFs 121-122).

Room 3

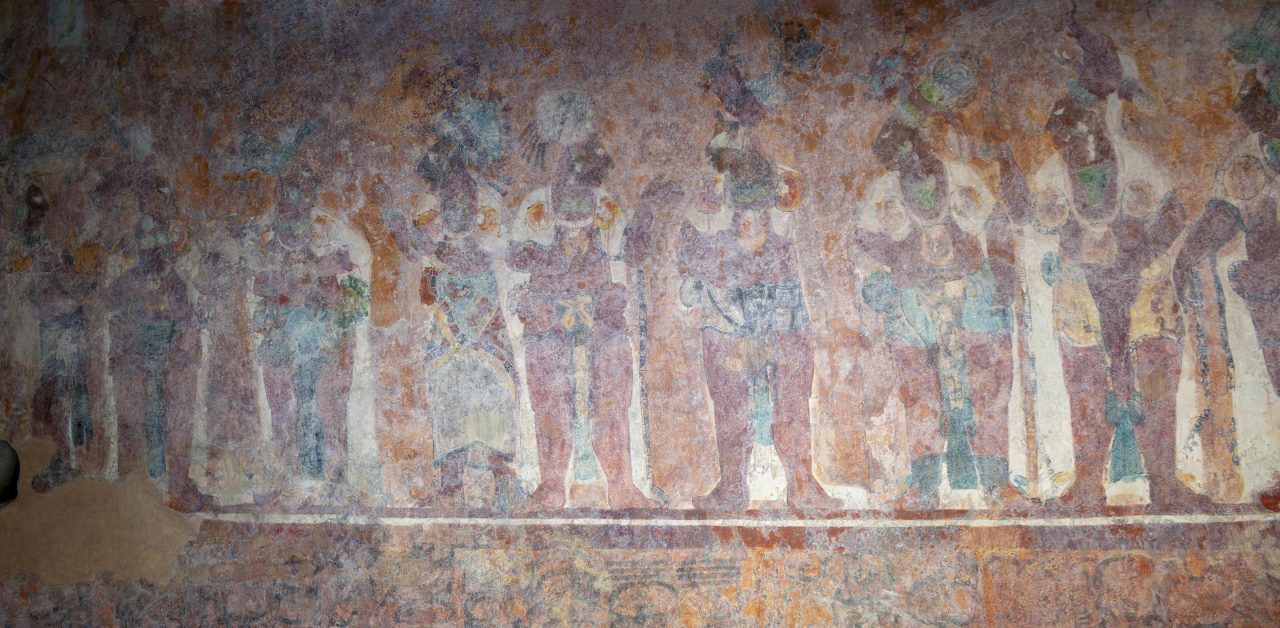

J_Bonampak 25-26. Late Classic Bonampak Structure 1, Room 3, north wall mural details animating standing dignitaries to lift and lower their hands in a gesture accompanying animated speech.

Even though the figures might represent different people, each individual’s hand gesture, frozen in the mural paint, in combination describes a single prescribed hand movement appropriate to the situation of conversing with other royalty. As the viewer moves their eyes along the standing figure line, the hand motions are completed in the viewer’s mind.

Animations extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:143, fig. 282 (HFs 57-58 and 59-60 [left to right]).

J_Bonampak 27

Animation of standing dignitaries to lift and lower their hands in a gesture accompanying animated speech. Bonampak West Room 3, upper north wall details.

Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:143, fig. 282 (HFs 52-53-54).

J_Bonampak 28

Late Classic Bonampak Structure 1, Room 3, lower west wall details animating the movements of a royal dancer.

As the viewer sweeps their eyes across the lower wall, the animation enlivens the dancer’s step, who pushes upwards from his knees, while raising and turning the fan he holds in his right arm. The dancer’s energetic movement is simultaneously accompanied by the swaying feathers of his high-reaching back rack.

Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:129, fig. 241 (HFs 27-28).

J_Bonampak 29

Late Classic Bonampak Structure 1, Room 3, upper details of south wall.

This animation visualises the energetic steps that might have been taken by one of the royal dancers performing on the temple steps depicted in the central scene of Room 3. While the two individual stills forming the animation likely represent different individuals, their combined movements animate the dance sequence taken as the viewer moves their eyes across the mural wall.

Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:129, fig. 241 (HFs 16 and 21).

J_Bonampak 30

Animation of the steps of a royal dancer, seemingly alighting like a bird. Bonampak West Room 3, lower south wall mural details.

Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:129, fig. 241 (HFs 26-25).

J_Bonampak 31

Animation of a musician shifting his position to blow a long horn to accompany royal ‘bird’ dancers. Bonampak West Room 3, lower north wall mural details.

Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:136, fig. 266 (HFs 46-47-49).

J_Bonampak 32 Animation of a staff and flag bearer mirrored across the lower east and west walls of Bonampak Room 3. The two figure pairs form ‘book ends’ for the row of seven young ch’ok dancers performing on the lower steps of the temple depicted across the east-south-west walls of Room 3.

Animation extracted and adapted from Miller and Brittenham 2013:129, fig. 241 (HFs 11-12 and HFs 44-43).

J_Bonampak 33

This Bonampak wall, Room 3, lower east section, animates a figure to extend a baton or staff while striving forwards (HFs 11-12).

J_Bonampak 34

Animation of an individual raising and lowering his flag. Bonampak West Room 3, lower north-to-south wall mural details (HFs 44-43).

Panels

J_Bonampak 35

Late Classic Bonampak Panel 1 details animating the movement involved in a seated figure lifting an Ux Yop Huun headband up to an enthroned ruler. The deity’s repeated handling in this manner reflects his role tied to themes of upward growth and fattening, such as accession to the throne (for more information on this deity see About the Project/ Time Gods and Animated Themes/ Ux Yop Huun).

Animation extracted and adapted from Schele IMG79055; accessed at http://research.famsi.org/schele.html.

La Venta / Chalcatzingo

In the same way as the Maya, the earlier Olmec, too, constructed pyramids in groupings of threes. At La Venta [1], the Olmec arranged at least one group of their colossal stone heads in three (González Lauck 2010:133-134). The colossal stone heads have since been moved and are therefore no longer positioned in the way in which they were originally found and intended to be viewed. Moving and positioning such massive stones would have required much effort by their makers, thus lending their initial placement symbolic significance. The heads exhibit varied facial expressions, in particular emphasising the changing shape of their mouths; this has led them to be described as talking (González Lauck 2010:134). Looking at the unseen connecting the Olmec heads, their circumambulation unlocks the possible animation of their changing facial expression and talking. Similar animations, albeit in miniature, occur as the three feet of two tripod ceramics from Lamanai, where, on rotation of the ceramic, each head displays variation suggestive of animation.

The Olmec heads, moreover, which vary in size, link ‘three’ to concepts of the three-part structure of time and growth. The concepts of three-part time, stone, sound (through talking) and animation are thus revealed. Consequently, it seems that ancient Olmec art used ‘three’ to structure their artworks in a similar way to the Maya and that they shared a similar philosophical outlook on time.

Wall Carving

J_Chalcatzingo 1

Details of a wall carving from Chalcatzingo revealing animation also present amongst the Olmec. As the viewer moves their eyes along the wall, a masked figure brandishing a spear is animated to step forward and advance on an individual lying prone at his feet. The advancing warrior simultaneously lowers the grip of his right hand on the spear handle in preparation of striking his victim, whose mask has slipped to one side to reveal his face.

Animation extracted and adapted from Benson 1996:114, fig. 9.

Chichen Itza

[1] Chichen Itza ‘Castillo’, the ‘stone’ of life and growth. To this very day, the stones of time (the ‘Castillo’, ‘Temple of the Thousand Columns’ and ‘Great Ball Court’) support the motion of visitors circumnavigating their structures.

When visiting Chichen Itza, it becomes clear how the site was built around three great ‘stones’ (structures). Visitors walk between these three stones, momentarily stopping to take photos, motion thus being balanced by stasis (as at Bonampak and other Maya sites). At the centre, the Castillo has been linked to time through the count of its steps and stairs, tying it, in particular, to the agricultural calendar. The Castillo therefore forms a time stone with a role tied to life and growth. Walking towards the west, visitors arrive at the Great Ballcourt, a stone structure linked to themes of death and sacrifice. While advancing a greater distance to the relative east, visitors arrive at the Temple of the Thousand Columns, celebrating beginnings and dawn. This structure revealed several Chac Mool statues, carved figures adopting a reclining position that creates an offertory ‘plate’ on their abdomen. The stance is similar to the birth position we describe in Maya Gods of Time, also shown adopted by Pakal on his sarcophagus lid at Palenque, tied to birth and new beginnings.

It is possible to imagine how all three Chichen Itza temples were once associated with sound and formed different acoustic spaces for worship, sacred theatres that probably housed mixed performances of music, dance and movement, as is painted on the walls of the Santa Rita structure (see Belize). In the west, the cheers and music and sound accompanying the motion of a game would have been amplified by the open vastness of the Great Ballcourt. Standing in the courtyard in front of the Castillo, its engineering allows us to experience a ‘whispering’ phenomenon. On the other hand, the acoustics of the Temple of the Thousand Columns, when its roof was still intact, would have been very different, likely echoing like a cave or cenote.

Walking between these three structures, we are now able to imagine how they came to symbolise the metaphor of the day, following the sun from east to west, and the cycle of our own life, through birth, growth and death; and how we are bound to the structure of three-part time. Consequently, when moving between these structures, we are encouraged to meditate on the nature of our own perception of time.

Panels

J_Chichen 1

Late Classic panel details of the Platform of the Eagles and Jaguars at Chichen Itza showing the triadic structure of time; three warriors are separated from each other by two eagles. From one depiction to the next there is a slight change in the relation between the eagles’ beak and heart: one eagle bites the heart, while the other does not. The three figures are similarly animated, their dangling ‘head’ pouches moving, with the depiction of the last figure’s pouch turning to face the other way (at viewer’s far right).

J_Chichen 2

Late Classic panel details of the Platform of the Eagles and Jaguars at Chichen Itza, animating the movement of a warrior and an eagle to feast on a heart. The animation is played out as the viewer walks along the panel in front of the temple.

J_Chichen 3

Carved details of the upper façade of the Gallery of the Monkeys, where, on passing by, the viewer animates the frenzied interactions between what might be individuals dressed in a bird and monkey costume. The one dressed as a bird prods the ‘monkey’ in the chest, causing the latter to defecate.

Animations extracted and adapted from Schmidt 2007:192, fig. 36.

Dzibilchaltun

At Dzibilchaltun, an ancient walking path (a sacbe) connects three sacred spaces: the Temple of the Seven Dolls (in the east), three central stelae, and a cenote and later on a Spanish Church with three steeples in the west. The ritual walking, moving from east to west, mimicked the path of the sun across the day sky and related to birth, life and death. In addition, the eastern Temple of the Seven Dolls was constructed to allow its three windows to be ‘activated’ with backlighting from the vernal equinox dawn sun, thus further associating solar time with the number three [2]. The site, furthermore, also revealed three eroded stone statues depicting ball-players, which once formed an animated sequence tying the motion of the ball game to three and time [3].

[3] One of three Dzibilchaltun ball player statues (only his legs and part of his torso remain) animating the movement of the ball game. Displayed in the Dzibilchaltun On-Site Museum.

Palenque

At Palenque, there is an imposing three-stone arrangement, built about a small and radial central platform, known as the Cross Temples Group. Of all the surviving Mesoamerican three-stone complexes, this one is possibly the most important. This is because the three tablets housed within the sanctuaries at the summit of each structure have survived, thus enabling study of their symbolic and epigraphic contents [6].

Our work reveals that walking between the three Palenque Cross Group temple ‘stones’ — as visitors feel compelled to do to this day — relates to the journey of the sun in the sky with the passing of the day; ascending and descending the temple stairs, the motion of ritual walking directly relates to the circular motion of time and the ‘rising’ and ‘falling’ sun in the sky. The three temples thus form a gigantic dedication to the Maya notion of three-part time.

One animation, of the sun rising during the day to its zenith position in the sky, was almost lost as the original tablet, housed in the eastern Temple of the Foliated Cross, had an ahaw head chipped away. It was only through studying a copy and a drawing of the intact tablet made by Alfred Maudslay in 1900 that the animation was brought to light.

Each of the three Palenque Cross Group temples was bound to a god. The largest (the Temple of the Cross) was dedicated to life-fattening growth (Ux Yop Huun); the lowest, positioned in the west (the Temple of the Sun) was related to themes surrounding death and creative destruction (Chaahk’s solar jaguar aspects), with the tablet visualising the sun ‘dying’ and setting into the earth; while the third (the Temple of the Foliated Cross) located in the relative east, was dedicated to fertile birth from water, and dawn (driven by K’awiil).

Our new perspective and deeper understanding of the tablets lies in recognising the becoming and what lies, unsaid yet implied, between the tablets. As with the animated sequences displayed on Maya ceramics and art elsewhere, we must fill in the ‘gaps’ of this successive sequence with the information gained from the surrounding scenes: the before and after.

At the Palenque palace, moreover, we know that the physical motion of the seventh century ruler K’inich Janab Pakal would have connected with three hieroglyphic steps leading into — and out of — House C. The steps are inscribed with glyphs that record events in Maya history. The text juxtaposes a battle the site lost against Calakmul in AD 599 with Pakal’s own victory over a probable Calakmul ally, Santa Elena, 62 years later (Stuart and Stuart 2008:140-143, 158-159); as a record of time, the text describing Pakal’s victory thus physically supported the motion of the royal king and his rule. The steps are bilaterally flanked by two groups of three portraits, which, on closer inspection, reveal the animation of one captive, possibly named as a captive from Santa Elena, changing arm positions to express an ancient gestural motion relating to grieving and submission [4; J_Palenque 1].

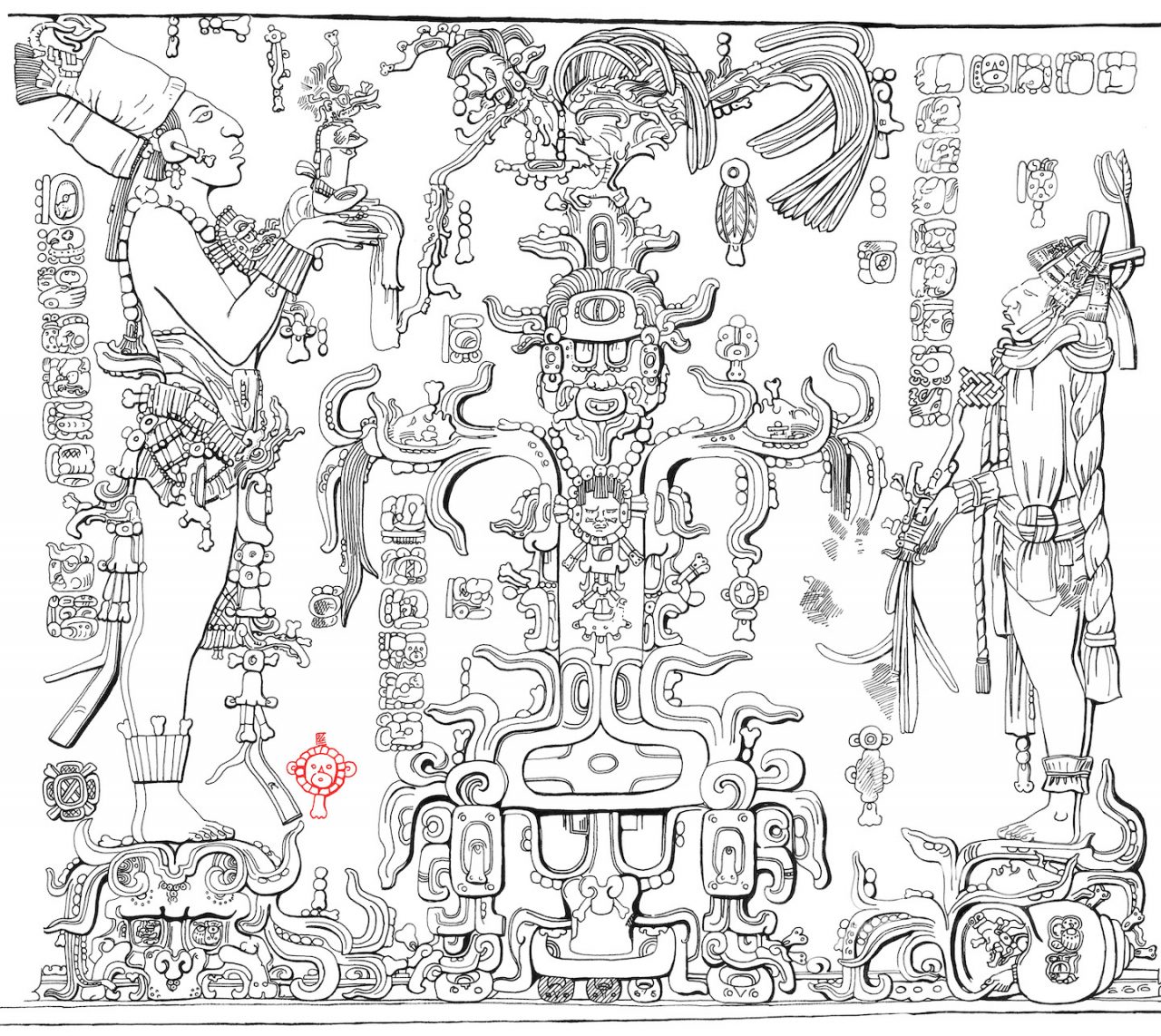

J_Palenque 1

Details of Classic period Palenque House C, Northeast Palace Court panels framing hieroglyphic stairway animating the captive on the viewer’s left to move his arms.

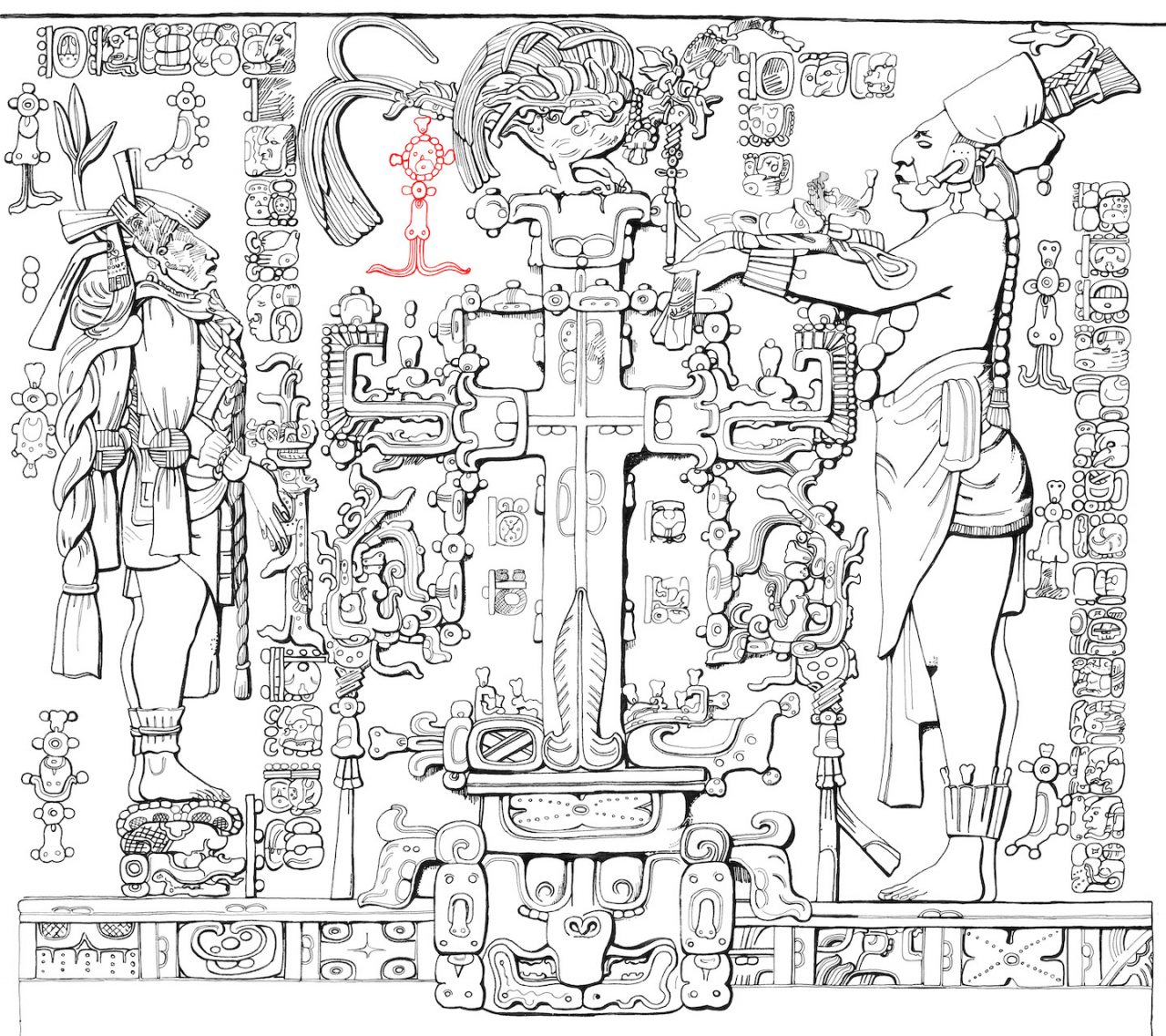

Classic period Throne Panel, from Palenque Temple XXI, showing the ruler K’inich Janahb’ Pakal flanked on his right by the ruler in function, Ahkal Mo’ Nahb’, and the heir to the throne, U Pakal K’inich, on his left [5]. The three central royal figures sit cross-legged and are framed either side by a kneeling supernatural, repeated twice, named Xak’al Miht Tu-muuy, who displays a jaguar body and paws, but rodent-like head and wears jaguar-pelt regalia and a tall, feathered headdress. The creature presents for the royals’ inspection feathers and long tassels tied into a bundle with three knots. The central ruler and Ahkal Mo’ Nahb’ lean to their right towards the creature’s apparition on the viewer’s left; the ruler shows it a bloodletting tool, implying that his offerings form an important part of the ritual depicted. K’inich Janahb’ Pakal’s heir, in turn, leans towards the jaguar creature’s apparition on the other side.

The composition of the throne panel imagery forms a merismus, reflected about the central ruler and his jaguar-pelt covered throne backrest. Either side, Ahkal Mo’ Nahb’ and U Pakal K’inich adopt mirrored poses, involving them holding their shoulder closest to the ruler with their opposing hand while resting their other hand on the opposite knee. When these two figures are superimposed into an animation [see 5.1 below], with the heir, U Pakal K’inich, flipped to face in the same direction as Ahkal Mo’ Nahb’, you see how their poses form one continues movement, involving the placement of their right hand onto their left shoulder; the gesture, along with their bowed heads, likely expresses reverence towards the king and their awareness of the sacred power of time driving the events depicted. Both figures sit on likely fire bundles, whose burning flames visualise the transformation of tangible matter into smoke and ash, also driven by time. Consequently, the artist(s), in planning the layout of the Throne Panel, incorporated the motion of time into his/their representation of the figures. However, the figure’s motion is at the same time contrasted with the stillness represented by the ruler, seated as the central strength of the chasmic arrangement in the very middle from which all movement radiates, like the ripples growing from the impact of a stone falling into a pool of still water. In this way, motion is balanced by stability, which the Maya saw as necessary in the successful working of their world (see Maya Gods of Time).

The Maya frequently animated figures, shown to perform one continues movement, using different individuals, sometimes also from earlier generations. By doing this, the Maya were showing their awareness of the historical re-occurrence of events played out by the elite members of their society over time; while the same rituals repeated over time by different individuals were always similar in their prescribed performance, they would never exactly match each other, thus balancing the stability promised by tradition with change (see Maya Gods of Time).

Next, the chiasmic reflection (merismus) structuring the Throne Panel spreads from the central ruler to include the repeated supernatural beast, whose two depictions, in addition, animate the movement of it carefully joining its jaguar paws, from the viewer’s left to its depiction on the right, to better present the bundle to the young heir, possibly having received some of the ruler’s blood along the way. The beasts’ two representations thus form the expression of one continuous movement performed by the creature, which becomes evident, as also shown in animation 5.1, when both depictions are superimposed with the figure to the left of the ruler flipped in order to face the other way [animation 5.2]. Simultaneously, the creature’s headdress grows in size (from the viewer’s left to right), in that the feathers lengthen, a corn cob sprouts from the mirror signs emerging from its very top, and three jester hat elements attached to the creature’s headband (the third is hidden from view on the other side), forming a feature of Ux Yop Huun, are now worn by little faces. The heads’ triadic repetition draws attention to the Maya notion of three-part time driving this Time God’s role to force growth and fattening, of maize and also U Pakal K’inich’s future accession to the throne; both events have been encouraged by the current ruler’s bloodletting. Triadic symbolism, reminding the viewer of the role of time driving the process, abounds in the panel imagery, including large and small three-dot ‘time’ clusters covering the ruler’s throne backrest, three knots chosen to tie the feathered bundles and number of jade or bone beads decorating the royals’ bracelets.

Panels

J_Palenque 2

Classic period Throne Tablet, west side, from Palenque Temple XIX, displaying the eighth century ruler Ahkal Mo’ Nahb III and an individual named Sajal-B’olon (‘Nine-Military Lord’) conducting a political ceremony in AD 731. Between the figure on the left and the right (the unseen), we can detect motion; his head tilts back, his right hand drops from his shoulder and his left palm moves down to press upon his knee. Simultaneously, his Ux Yop Huun headdress grows and he lifts the spotted, soft handle of a rectangular pouch or basket trimmed with feather tassels with his right hand up to his left shoulder; the object displays a centrally ‘spinning’, three-spoked scroll wheel, a mnemonic to three-part time driving the figure’s movements.

Displayed in the Museo de Sitio de Palenque, Alberto Ruz Lhuillier.

J_Palenque 3

Late Classic stone tablet recording the crowning ceremony of the seventh-century Palenque ruler K’inich Ahkal Mo’ Nahb. Three nobles seated on either side of the ruler form a clear conceptual reference to the transformative power of three-part time and animation. The arm and hand positions of the two triadic figure groups seated either side of the king change to express their devoted attention to his being: on the right, the figures’ arms, crossed over chest by the first at the far right, are lowered and opened towards the king; on the left, the triad gradually lifts an Ux Yop Huun headband from the first figure’s lap, at the far left, up and into the air for the lord’s inspection. Temple XIX, Interior Platform, south face.

Displayed in the Museo de Sitio de Palenque, Alberto Ruz Lhuillier.

Pier panels

J_Palenque 4

Details of three – of a series – of Palenque Classic period tablets adorning the exterior of the Palace, House C, Western Piers, which, when the viewer moves between them, animate an enthroned ruler to lift his right arm.

Even though the rulers’ depictions might represent different individuals, over time, they are shown involved in a ceremony that was played out in an animated sequence to communicate the Maya notion of time driving historical reoccurrence. The Maya recorded periodically-repeated elite rites in this manner to mark the progression of time and their acceptance of historical reoccurrence; see also other Palenque pier animations (2-8).

Animation extracted and adapted from Maudslay 1889-1902, vol. 4, plate 28.

J_Palenque 5

Details of two – of a series of many – similar panels decorating the Temple of Inscriptions at Palenque. As the viewer passes by, the royal shown holding an infant and serpent slightly lowers the outstretched arm with which he supports the serpent’s body.

The serpent, representing the waters of the world, is symbolic of the infant’s birth (see Maya Gods of Time).

Even though the individuals’ depictions likely represent different rulers over time, the infants’ presentation ceremony is played out in an animated sequence to communicate the Maya notion of time driving historical reoccurrence, as repeated events that were periodically re-enacted by the elite at the site; see also other Palenque pier animations (1-8).

Animation extracted and adapted from Maudslay 1889-1902, vol. 4, plate 55 (left and right).

J_Palenque 6

Details of panels decorating the eastern piers of Palace House A at Palenque. Even though the rulers depicted might be different individuals, their representation in identical situations, a ceremony attended by two subjugates, suggests that the Maya recognised the concept of historical reoccurrence; this repetitive recycling of historical events the Maya artistically represented by incorporating animation (slight change in movement of the figures) from one panel to the next and which is activated when the viewer passes by in front of the piers (see Maya Gods of Time). There are many more panels decorating the Palenque Palace piers, which, although largely eroded, still retain enough imagery to show them forming part of the same visual programme that includes animation to draw attention to the historical occurrence of a ceremony important to Classic period Palenque royalty.

Animation extracted and adapted from Maudslay 1889-1902, vol. 4, plates 10-11.

J_Palenque 7

Pier details adorning Palenque Palace House D animating a royal to decapitate a figure seated on long-nosed Time God head stones. The royal swings the axe from above his head while grasping the victim’s hair to pull him forward and expose his neck.

As in [J_Palenque 4-8], even though the figures portrayed might represent different individuals, the piers’ sequential physical placement and identical symbolic theme once again suggest the Maya notion of animation also expressing historical reoccurrence (See Maya Gods of Time).

Animation extracted and adapted from Maudslay 1889-1902, vol. 4, plates 34 (far right) and 37.

J_Palenque 8

Palenque Classic period tablets adorning the exterior of the Palace that, even though very eroded, still show the animation of a ruler turning and bending towards a figure, forcing him to kneel before him.

Even though the rulers’ depictions might be those of different individuals, the ceremony is played out in an animated sequence to communicate the Maya notion of time driving historically-reoccurring events that were periodically re-enacted by the Palenque elite.

Animation extracted and adapted from Maudslay 1889-1902, vol. 4, plates 35-36.

Tablets

[6] Movement expressed by a sun symbol between the Cross Tablet (left) and Foliated Cross Tablet (right), Palenque. The sun symbol is shown to rise to the top of the panel (highlighted red). After Maudslay 1889-1902, vol. 4, plates 75-76 and 81.

Tulum

[1] The coastal cliffs supporting Tulum, where tourists diving into the blue Caribbean waters mimic an ancient Maya stucco figure animated to dive from above a nearby temple doorway [3].

Tulum is a Postclassic Maya site perched high on a clifftop overlooking the Caribbean Sea. It is one of the most picturesque Maya sites, receiving thousands of visitors each year flowing in from the booming beach tourism developing on this stretch of Yucatan coastline.

On a beach holiday, these visitors may experience how their own action of plunging into the turquoise sea to cool off mimics that of an ancient stucco figure animated to dive, in a sequence of three, from above the three doors of Structure 16 [3]. Consequently, visitors can connect their subjective experience of the moment, that is, before and after their immersion into the sea, with the ancient Maya artwork and their own perception of three-part time.

Another Tulum temple, Structure 5, is also physically bound to time and the cyclical rhythm of the sun through a small window positioned in its eastern wall which frames the rising sun on vernal and autumnal equinox mornings. The Maya name for the city was Tzama meaning ‘City of Dawn’. In contrast, the western sides of Tulum structures predominantly portray diving figures [3]. Rising from water represented a Maya expression of birth and life, while entering, or diving, into water formed a metaphor for death (see Maya Gods of Time).

Panels

Yaxchilan

The ancient site of Yaxchilan is nestled in a bend of the bank of the Usumacinta river that forms the border between Mexico and Guatemala. The relative isolation of Yaxchilan, compared to other Maya sites, has likely contributed to most of its carved stone triads, bound to time and animation, having remained at the site, thus facilitating their reading. There are some exceptions, however, such as Lintels 24 and 25, now in the British Museum, London, and Lintel 26, displayed in the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, originally all supporting the three doorways of Yaxchilan Structure 23.

Consequently, Yaxchilan offers many artworks structured in three, such as stone lintels supporting doorways and stelae grouped in three. The Austrian explorer and photographer Theobert Maler (1901-1903:109, 160-162) noted that fires had been lit beneath groups of three lintels at Yaxchilan; the fires likely pertained to the three-part structure of time in relation to the fiery sun as evident in Postclassic fire rituals (see Maya Gods of Time). Again, the motion of viewing the artworks by circumambulation is key to unlocking their animations. Similarly, the motion of the ballgame was played at Yaxchilan about three circular stone markers, placed to run along the centreline of the court floor; three stones of time therefore supported the motion of the game. Finally, the dedication or emphasis Yaxchilan placed on concepts surrounding time are evident from a cylindrical carved stela forming the style of a sundial that was placed in prime position in front of Structure 33 and its three carved lintels [2].

[2] A cylindrical carved stela placed before Yaxchilan Structure 33 forms the stone style of a sun dial. Since the photo was taken at midday, the style casts little shadow.

Lintels

The motion of walking the few metres between Yaxchilan Lintels 13 and 14, supporting two of the doorways leading into Structure 20, connects with memory to create the animation of the lord slightly altering his hand position to tilt the bowl from which a serpent maw emerges towards the royal lady on the viewer’s left, who, simultaneously, moves the bloodletting tool she holds in her right hand.

Animation extracted and adapted from Chinchilla Mazariegos 2017:125, 127, figs. 51 and 53.

Above are details of Late Classic Yaxchilan Lintels 13 and 14 forming an animation pair; Lintel 13 was found on the ground before the central doorway of Structure 20 and Lintel 14 was still in place above its northwest (right-hand) door (Graham and Euw 1977:35-37). The lintel pair animate Lady Chak Chami proffering a ceramic bowl towards her husband or consort, the sajal Bird Jaguar IV, who supports, with his raised right hand, the lower jaw of a large, bearded serpent or skeletal centipede; the creature rears up from behind Lady Chak Chami to bring forth their probable future child Shield Jaguar IV (Graham and Euw 1977:37). All three figures wear Ux Yop Huun headbands signalling growth and likely, in this instance, Shield Jaguar IV’s future royal ascension.

Moving from one lintel to the next, Lady Chak Chimi slightly tilts the bowl towards the apparition, who lowers his head and hands in order to lean in and converse more intently with the lady; Shield Jaguar’s hand gesture involves him tightly holding his left wrist with his right hand, whose fingers change from one lintel to the next in that he initially forms an ‘o’ by touching together his thumb and index finger while extending the rest, to unfurling all the fingers of his left hand. Simultaneously, his parents Lady Chak Chami and Bird Jaguar slightly lower the bloodletters they hold in their hands, indicating their offerings which brought forth Shield Jaguar’s apparition or, possibly, birth. Moreover, Chahk Chami’s bloodletter appears attached to the centipede creature’s tail, which she clamps under her right arm, directly linking her blood offering to the appearance of the vision.

Yaxchilan Lintels 53 and 54 form another animation pair. The lintels animate subtle movement of a royal male and female in their interaction with each other, which transfers to their costume elements, for example moving their feathers. Even though the two lintels were associated with different structures on discovery, Lintel 53 was found lying face down in front of the west door of Structure 55 and Lintel 54 in front of the central door of Structure 55 (Graham 1979:27-30), the two structure stand side-by-side and the lintels, which had no longer been in-situ on discovery, might have been moved from their original position.

Stelae

J_Yaxchilan 3

Late Classic Yaxchilan Stela 11, human side, depicting the ruler Bird Jaguar wearing a Chaahk mask while holding an axe and a K’awiil ‘sceptre’ above the head of a captive; the captive is represented three times to animate his prostration before the king.

Photo after Maler 1901-1903, plate LXXIV. Animation extracted and adapted from Hellmuth 1987:93, fig. 128, courtesy of Linda Schele.

X’telhu

J_X’telhu 1

Details of a panel from X’telhu, located southwest of Yaxuna, Yucatan, animating a figure pair to move along the body of a long, crocodilian creature with wide-open maw (depicted in the original).

The taller figure wears a large, long-snouted headdress with long feathers attached that sway while he lifts up a probable deer antler and moves along the reptile’s body; the smaller figure wears a jaguar-pelt cape.

Animation extracted and adapted from Freidel 2007:359, fig. 8.

Teotihuacan

Teotihuacan was built at the centre of a large basin surrounded by three imposing mountains. The city planning mimicked the same triadic pattern, aligning three main structures along a grand central avenue: the Temple of the Sun, Temple of the Moon and the Ciudadela, containing the Temple of Quetzalcoatl. Once again, the motion of walking links these three sacred ‘stones’ to the ‘unseen’ spaces in between. The number of the temples also connects to the conceptual idea behind the three feet (often decorated with Ik’ ‘wind’ symbols) chosen to support the many tripod ceramics excavated at the site. The circumambulation of these giant ‘stones’, or turning of the ceramics, activates the symbolism displayed on their surfaces. The largest stone or temple, the Temple of the Sun, is framed either side by the two smaller ones, which is similar to town planning patterns we have also detected in the Maya world. The Teotihuacan temples have long been studied for their connection to the calendar and time. Ascending the steps of the massive Temple of the Sun is comparable to climbing the Castillo at Chichen Itza or the Temple of the Cross at Palenque, where pilgrims or priests ‘rose’ and ‘fell’ like the sun in the sky, comparable to the waxing and waning of life and our growth towards our zenith and then gradual decline towards death.

The most northern of the three Teotihuacan temples is related to nocturnal themes, dedicated to the moon and therefore likely the end of day. Passing the largest stone in the alignment, the Temple of the Sun, in the centre, the most southern temple is situated within the Ciudadela compound, containing the temple dedicated to Quetzalcoatl, and positioned in the very east of this compound; it is related to themes of birth and beginnings. Shells surrounding undulating serpents decorate its façade and mirrors were found buried within; moreover, the courtyard surrounding the structure was designed to allow its flooding to create an enormous water surface that would have reflected the temple structure to form a gigantic chiasmic reflection of its symbolism. Consequently, this Quetzalcoatl ‘stone’ aligns with genesis and the beginning of creation.

The Maya Time God K’awiil and Mexican Quetzalcoatl share many traits; both are closely associated with themes of reflection and beginnings. We have proposed that such pairing or duality leads to creation, as in male/female producing offspring; that is, two similar, yet imperfectly-different, reflected halves generating something new. At Teotihuacan, a feathered and other serpentine creature are repeated several times entwining the temple, reflected in the water pooled in the Ciudadela courtyard below. The temple exhibits several imagery tiers repeating the reptiles and their surrounding shells. Tiers displaying profile views of the two reptiles’ alternating bodies, terminating in three-dimensional frontal depictions of their heads, alternate with tiers displaying profile views of the head and undulating body of the feathered specimen; shells are reflected across the latter’s bodies.

At Tulum, K’awiil (and serpents) also occur reflected about the rising sun in a mural depicted on the eastern edge of this most eastern Maya settlement, dedicated to birth and the dawn sun rising each morning from the Caribbean Sea (see Tulum [1]); Tulum or the City of Dawn represented an eastern city dedicated to beginnings and creation.

Ceramics

J_Teotihuacan 1

Teotihuacan stucco tripod bowl details animating, on turning, an individual hunting birds with a blowpipe. The flight of the birds is animated by their repeated depiction as circling a plant exhibiting three flowers, their spinning motion reminding the viewer of the unending circular motion of time, which follows a cyclical progression from birth, to growth, to death.

Animation extracted and adapted from Berrin and Pazstory 1993:130, fig. 2.