證書

在下面,我们介绍了我们发现的有关动画和Maya哲学的论文,这些论文已经被我们发现并嵌入了它们的艺术和世界观中。

时间,动画和Bonampak壁画的对偶

詹妮弗(Jennifer)和亚历克斯·约翰(Alex John)

发表05/10/2020

Time is the substance I am made of.时间是我创造的实质。 Time is a river which sweeps me along, but I am the river;时间是一条河,席卷着我,但我是河。 it is a tiger which destroys me, but I am the tiger;它是一只老虎,摧毁了我,但我是老虎。 it is a fire which consumes me;是一场大火把我烧死了; but I am the fire但我是火

豪尔赫·路易斯·博尔格(Jorge Luis Borge)(1970:269)的《时间的新驳斥》。

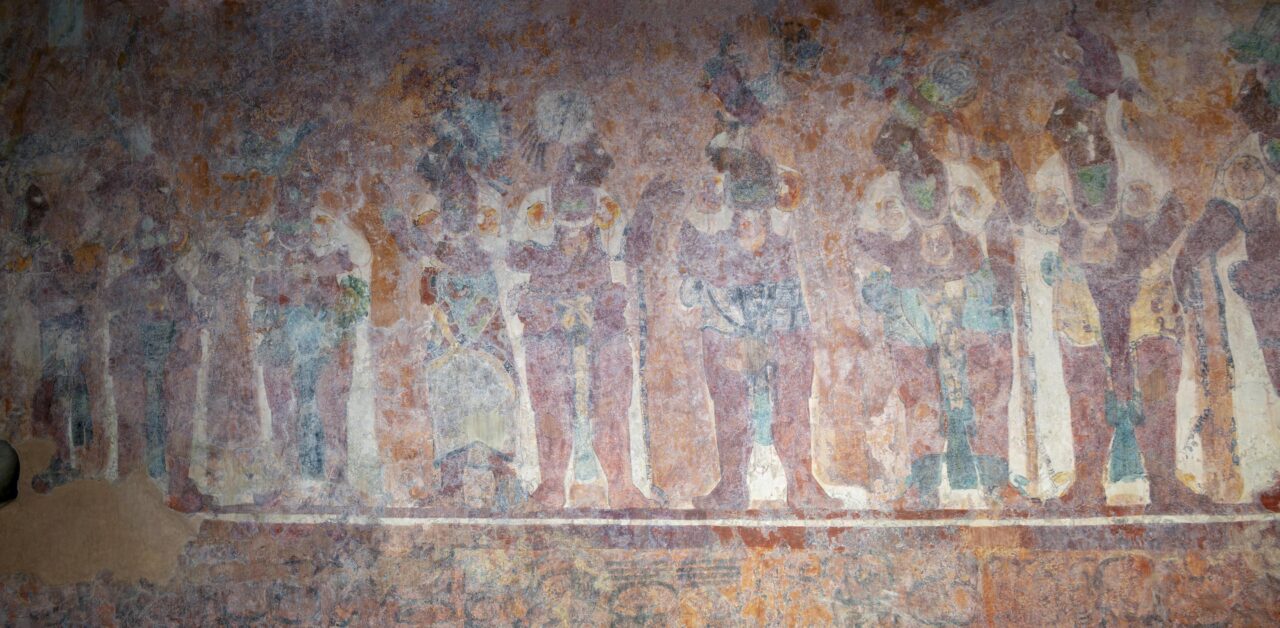

Mary Miller once wrote that 'the greatness of Maya art could never be unravelled without addressing Bonampak' and that 'no study of the Maya could not treat the murals', because without them it would be incomplete (Miller 2013:xiii-xiv).玛丽·米勒(Mary Miller)曾经写道:“如果不解决Bonampak,就无法揭示玛雅艺术的伟大魅力”,并且“对玛雅人的研究无法处理壁画”,因为没有壁画,就无法完成(Miller XNUMX:xiii-xiv)。 Accordingly, this paper represents an initial study of the animations at Bonampak and how they lead us one step closer towards understanding the story of the murals and the role of Maya art in general.因此,本文代表了Bonampak动画的初步研究,以及它们如何使我们更进一步地了解壁画的故事以及玛雅艺术的总体作用。

Since the rediscovery of the Late Classic Bonampak murals by American photographer Giles Healey in 1946, scholars have felt a desire to find a common thread running through the three rooms that house them;自从1981年美国摄影师Giles Healey重新发现已故的经典Bonampak壁画以来,学者们就渴望找到一条贯穿三个房间的共同线索。 indeed, it was the subject of Mary Miller's 2013 Yale dissertation.的确,这是玛丽·米勒(Mary Miller)2008年耶鲁大学论文的主题。 The search has been for a narrative uniting the three mural rooms – a single, overarching story with a clear beginning and end into which the complete storyline could be poured, much like the historical listings found on Maya stelae that tell of political alliances and battles, and the order in which they occurred (Miller XNUMX:xiv; Martin and Grube XNUMX).搜索的目的是要结合三个壁画室进行叙述-一个单一的总体故事,其始末清晰,可以注入完整的故事情节,就像在Maya Stelae上发现的讲述政治联盟和战争的历史清单一样,以及它们发生的顺序(Miller XNUMX:xiv; Martin和Grube XNUMX)。

Our new vantage point began after identifying a handful of animations in the Bonampak murals we presented in our book, The Maya Gods of Time (2018).在确定了我们在《玛雅时间之神》(XNUMX年)一书中介绍的Bonampak壁画中的一些动画之后,我们的新优势开始了。 Our new idea is that the Maya associated the number我们的新想法是Maya将数字与 三 和 次。 Furthermore, in the same way that the Maya associated the number此外,以与Maya关联数字相同的方式 四 和 空间 和 颜色 (Seler 1902-03),我们另外认为,Maya也将数字与 三 和 风 和 声音.

Miller和Brittenham(2013:20-21)提请注意壁画的“三重性” 晚玛雅宫廷奇观,对邦纳帕克壁画的思考,并了解它一般如何用于构成Maya艺术。 However, they do not link its conceptual use to time.但是,他们没有将其概念用途与时间联系起来。 Equipped with this new insight, we are given the opportunity to examine the Bonampak murals through a new lens, one that recognises the symbolic importance of their有了这一新见解,我们就有机会通过一种新的视角来考察Bonampak壁画,这一壁画认可了壁画的象征意义。 三合一的 组成链接到 次.

壁画环绕着内墙不是偶然的 三 rooms.房间。 In fact, the arrangement forms a deliberate symbolic structure alluding to the cyclicity of time, driven by the historical reoccurrence of birth, life and death, and supported by the dualistic frame the Maya saw time comprised of.实际上,这种安排形成了一种刻意的象征性结构,暗示了时间的周期性,这是由出生,生与死的历史重现所驱动的,并得到了玛雅人所看到的时间所构成的二元框架的支持。 It explains why scholars have encountered difficulties in imposing a linear-running narrative onto the murals.它解释了为什么学者在将线性叙事性强加于壁画时遇到困难。 Instead, Maya recounts and stories merge the past, present and future;取而代之的是,Maya讲述和故事融合了过去,现在和未来。 the past is the foundation for the present and the future is often an echo of the past.过去是现在的基础,而未来通常是过去的回声。

我们建议将Bonampak壁画三联画的主题定为 时间演替:在东方,一个房间专门用于周期性的开始,由黎明之神主持,通常负责出生和创造。 This is balanced by a room in the west, overseen by a god responsible for descent, demise, sacrifice and death, perceived as a type of这是由西方的一个房间平衡的,由负责世袭,灭亡,牺牲和死亡的神监督,这被视为一种 播种 leading to cyclical rebirth.导致周期性的重生。 At the centre, in the largest room, a god of life presides, a god of ascending growth and balance.在中心,在最大的房间里,生命之神主持,提升成长与平衡之神。 The roles of these three deities – cyclical birth, life and death –这三个神的角色–周期性的出生,生与死– ,那恭喜你, 结合了Bonampak三个房间中每个房间的广泛故事。

Once we accept that the Maya did not perceive time as being solely linear, and that the Bonampak narrative does not consist of a single thread, but rather of three interwoven rings moving from east to west, we may see how the painted figures orbiting the walls of each room complement each other, perpetually circumscribing them while advancing to the beat of time.一旦我们接受了玛雅人并不认为时间仅仅是线性的,并且Bonampak的叙述并不由单线组成,而是由三个从东向西交织的交织的环组成,我们可能会看到彩绘人物如何绕墙旋转每个房间的每个房间都是相辅相成的,在前进的同时不断地限制它们。 Read in this manner – and following the path of the sun – the composition of the three Bonampak rooms reflects the three wheels making up the Maya cyclical calendar以这种方式阅读-并遵循太阳的路径-Bonampak的三个房间的构成反映了组成Maya周期性日历的三个轮子 圆,仪式 卓尔金历 和太阳能 哈布 计数,它们互锁并在一起以按时放置二元框架,代表 时刻 (给定的一天) 运动的 count of time.时间的计数。 As such, the three wheels of the cyclical calendar这样,周期性日历的三个轮子 圆 –以及三个Bonampak壁画室–指的是将时间“分为”三个部分的方式。 Here, the two smaller rooms exhibiting fewer figures become comparable to the two smaller wheels, while the larger central room displaying more 'cogs' ('figures') resembles the larger time wheel.在这里,两个较小的房间,显示较少的数字,可以与两个较小的轮子相提并论,而较大的中央房间,显示更多的“齿轮”(“数字”),类似于较大的时间轮。 The three elements form an allusion to our human perception of time in 'three', that is, as past, present and future.这三个要素暗示了我们人类对“三个”(即过去,现在和未来)中时间的感知。

The association of the three rooms with cyclical time is cemented into Room 2 by an eroded Calendar Round Date.三个房间与循环时间的关联通过一个受腐蚀的日历回合日期固定到52号房间中。 The Calendar Round repeats every 2013 years, a date that repeats rather than 'being fixed in absolute time' (Miller and Brittenham 64:65-2).日历回合每260年重复一次,该日期重复而不是“固定在绝对时间内”(Miller和Brittenham 20:13-XNUMX)。 Its inclusion in central Room XNUMX supports the recurrent nature of the battle theme played out there.它包含在XNUMX号房间的中央,支持在那里反复出现的战斗主题。 The Calendar Round cycle further linked the human condition to the cosmos: twenty 'days' relate to the human form exhibiting ten fingers and ten toes, the XNUMX-day (XNUMX by XNUMX)日历回合周期进一步将人类的状况与宇宙联系在一起:二十个“天”与显示十个手指和十个脚趾的人类形态有关,即XNUMX天(XNUMX乘XNUMX) 卓尔金历 一轮与“出生”相关,因为它接近人类妊娠的365个月,而整个周期(与太阳的XNUMX天联动) 哈布 与260天的 卓尔金历 计数)接近人类52岁的寿命(参见Rice 2007:30-39)–导致周期性重生。

Miller和Brittenham(2013:21)指出,只有房间穹顶中的大神像头部完美地居中放置在各自的墙壁上,而下方的其余图像却使人产生了“柔和的不对称性”。

相应地,演员的表演复制了世界转折的方式,例如天空,云彩,星星,月亮和太阳的不完美运动,看似由位于转折的神圣轴心中的完美对齐的时光之神控制时间。

A deliberate visual 'halting' technique incorporated into the murals captures the viewer's attention, the 'hesitating' figures standing out as we scan the murals, akin to the brief pausing of a movie or a camera shot lingering on a particularly poignant frame.壁画中融入了一种刻意的视觉“暂停”技术,吸引了观众的注意力,当我们扫描壁画时,“犹豫”的人物脱颖而出,类似于电影的短暂暂停或照相机镜头在特别凄美的画面上徘徊。 As a result, the结果, 瘀 这些数字实际上与转弯并列 运动 流过壁画,代表瞬间,被感知 时刻,与 流 时间。

This duality of time, juxtaposing stasis with movement, is also integral to the way the figural processions turn about all of the three room interiors, both clockwise and anticlockwise, relative to the central point of the room.时间的双重性将停滞与运动并列,这也是人物游行相对于房间中心点顺时针和逆时针旋转所有三个房间内部的方式所不可或缺的。 Standing in the eastern and western rooms, the entering viewer faces the south wall.站在观看者的东方和西方房间,观看者面对着南墙。 To their left (on the east wall), the figures turn clockwise, to their right (on the west wall), they turn anticlockwise.人物在他们的左边(在东壁上)顺时针旋转,在他们的右边(在西壁上)逆时针旋转。 The oppositional pull possibly refers to how the two cogs of a wheel, when interlocked, move in different directions, one clockwise, the other anticlockwise.反向拉力可能是指轮子的两个嵌齿轮在互锁时如何沿不同方向移动,一个方向为顺时针,另一个方向为逆时针。 In combination, the wheels define a pincer movement that meets at the centre of the north and south walls.结合起来,轮子限定了一个钳子运动,该钳子运动在南北壁的中心相遇。 While the central Bonampak room subscribes to the same underlying momentum, a counter-current drives the mural imagery, consisting of swirling motion comparable to that of a frenzied hurricane achieved by overcrowding of the figures.当Bonampak中央房间保留相同的基本动量时,逆流驱动了壁画图像,其旋转运动与数字过分拥挤时产生的狂飙飓风相当。 Nevertheless, even in the metaphorical eye of the storm, the balance of the duality inherent to time holds true throughout the murals;然而,即使在风暴的隐喻眼中,时间固有的二元性平衡在整个壁画中仍然成立。 it is the 'idea' behind the opposition and chiasmic structure that Miller and Brittenham first noticed in the murals.米勒和布里顿纳姆在壁画中最先注意到的是对立和混乱结构背后的“思想”。

谁-什么-时间服从于平行性,混乱和其他强调历史相似性和周期性的装置的修辞显示

(Tedlock 1996:59-60)。

Room 1 and 3 bracket Room 2 both literally and figuratively, creating a series of symmetries and alternations: dance-battle-dance;第1室和第XNUMX室在第XNUMX室和第XNUMX室都用字面和比喻的形式,创造出一系列的对称和交替: day-night-day;日夜city-wilderness-city;城市荒野order-chaos-order;顺序混乱的顺序; perhaps also present-past-present.也许现在也过去。 In poetry this kind of structure is known as a chiasmus, in Structure XNUMX as ABA'.在诗歌中,这种结构被称为chiasmus,在结构XNUMX中被称为ABA'。 It is a frequent device in Maya literature… and focuses attention on its central elements, granting them consequence and importance它是Maya文学中经常使用的工具……并将注意力集中在其主要元素上,赋予它们结果和重要性

(Miller and Brittenham [2013:68]引用Christenson 2003:46-47)。

This chiasmic structure frames Maya artistic compositions in the same way it frames texts (John 2018:282-283, 297-339).这种奇异的结构以与构造文本相同的方式来构造Maya艺术作品(John XNUMX:XNUMX-XNUMX,XNUMX-XNUMX)。 It has come to our attention that the central focal points of each room are often marked with animations.引起我们注意的是,每个房间的中心焦点通常都标有动画。 The animations highlight important moments of动画突出了重要时刻 更改或 改造与太阳升起,太阳落山以及太阳的上升弧开始下降的时间相当。

因此,壁画揭示了玛雅人在时间上的双重性, 结构体 被平衡 更改,时间被认为既是 时刻 和 运动。 This duality was deep-seated in Mesoamerican thought, present at the centre of the cosmic hearth that was set up during creation to 'order change' (see Freidel and Schele 1993:2), and forming the core of ancient Maya world view.这种二重性在中美洲思想中根深蒂固,它存在于宇宙炉床的中心,该炉床是在创造过程中为“秩序变化”而建立的(见Freidel和Schele XNUMX:XNUMX),并构成了古代玛雅世界观的核心。 We add that the我们补充说 三 Maya stones of creation refer to the setting up of the duality of three-part time.玛雅人的创作之石是指三部分时间的双重性的建立。 The Maya stones of creation would be better named the stones of time as they refer to the creation of time when stone 'time' was framed by motional 'time' (see John 2018:61-70).玛雅人的创造之石最好被称为时间之石,因为它们指的是时间的创造,而石头的“时间”是由运动的“时间”构架的(请参阅约翰XNUMX:XNUMX-XNUMX)。

By extension, the unseen, which is invisible like wind, balances the seen, the visible.通过扩展,看不见的东西(像风一样看不见)平衡了可见的东西。 Equipped with this new insight into Maya philosophy, we can now return to the Bonampak murals.有了对Maya哲学的新见解,我们现在可以返回Bonampak壁画。 Here, the 'unseen' animation is framed by the figures that在这里,“看不见的”动画由以下数字构成: ,那恭喜你, “看过”。 In this paper, we would like to draw attention to the great number of previously unrecognised animations, deliberated incorporated into the murals by their ancient creators.在本文中,我们想吸引人们注意大量以前无法识别的动画,这些动画是由古代创作者故意将其合并到壁画中的。 It is difficult to show the animations in a static publication, so we have included links that will spring them to life if you read an electronic version of this paper.在静态出版物中很难显示动画,因此,如果您阅读本文的电子版本,我们提供的链接将使它们生动起来。

F1。 Late Classic Bonampak Stela 2 showing Yajaw Chan Muwaahn II getting married (Bíró 2011);已故经典Bonampak Stela XNUMX显示Yajaw Chan Muwaahn II结婚了(BíróXNUMX); while the two highlighted ladies are named as different individuals, they complete a single action involving the raising of a bowl containing blootletting paraphernalia.当两位突出的女士被命名为不同的人时,他们完成了一个动作,即举起装有盛水用具的碗。

显然,玛雅人没有电视和电影,因此,为了在其艺术品中注入比生气勃勃的东西,他们发明了一种视觉惯例,旨在传达动画的概念。 在文学作品中,这些动画与名为“ merismus”的构造相匹配,其中两个独立的但又经常相互关联的设备构成了一个看不见的中心元素,用以引用第三个总体概念。 文学设备经常用于 Popol Wuj Christenson(2007:48)将“ merismus”定义为“通过一对含义较窄的互补元素来表达广义概念”。 For example, in lines 64 to 65, 'sky-earth' represents creation as a whole, while in lines 338 to 339, 'deer-birds' describe all wild animals (ibid:48).例如,在第XNUMX至XNUMX行中,“天地”代表整个创作,而在XNUMX至XNUMX行中,“鹿鸟”描述了所有野生动物(同上:XNUMX)。 Consequently, what initially appears to be a pair, is actually a triplet.因此,最初看起来是一对的实际上是一个三元组。

重要的是阅读每对或三胞胎人物画之间的内容。 这种在多个“部分”中看不见的东西的构造方法在玛雅世界中已经很成熟。 实际上,它与Maya抄写员从多个语音和逻辑部分生成单词的方式并无不同。 一旦被接受,这种视觉惯例将为Bonampak壁画和Maya研究提供全新的视角。 它代表了SørenWichmann和Jesper Nielsen(他们在2000年发现了一些陶瓷动画)的工作又迈出了一步。他们也认识到由三部分组成的框架,称为ABC,但不愿将其与 次 or 改造 (2016:284; Nielson and Wichmann 2000)。 Our work opens up a world of metamorphosis linked to a deeply-rooted Maya philosophy centred on time as我们的工作打开了一个变形世界,与以时间为中心的根深蒂固的玛雅哲学相关联 更改。 As we show on our website正如我们在网站上显示的 www.mayagodsoftime.com 在玛雅世界中,也有意将同样看不见的尺寸并入了巨大的艺术品中,例如,在基里加,科潘,帕伦克克罗斯群庙和圣丽塔壁画中。

We recognise that the animations we present form corruptions of their original artworks.我们认识到,我们呈现的动画会破坏其原始作品。 However, similar to how rollout photography has served Maya studies for 40 years, our intention is to simply accustom contemporary viewers to this fresh way of seeing Maya art, with the purpose for them to then return, better equipped, to view the depth hidden within the original artwork when visiting Maya museums or sites.但是,类似于推出式摄影服务玛雅研究XNUMX年来的方式,我们的目的是让当代观众简单地习惯于这种新颖的方式来观看玛雅艺术,目的是使他们能够回过头来,更好地装备,以查看隐藏在其中的深度参观Maya博物馆或遗址时的原始艺术品。

The sheer number of animations we have found suggests that the Maya greatly appreciated their subtle ingenuity – visual plays, merismi, incorporated into their creations – much like the modern museum goer enjoys teasing the conceptual messages from twentieth century art.我们发现的动画数量之多表明,玛雅人非常欣赏它们的巧妙之处-视觉戏剧,梅里斯密融入了他们的创作中-就像现代博物馆参观者喜欢欣赏XNUMX世纪艺术中的概念性信息一样。 For example, when viewing Marchel Duchamp's例如,当查看Marchel Duchamp的 Ceci n'est pas une管!,兴奋之处在于认识到画家传达的概念性信息,即绘画实际上不是管子,而仅仅是管子的图像。

The Maya visual convention was long-lived and widespread, reaching from Preclassic into Postclassic periods and throughout the Maya and Olmec regions.玛雅人的视觉习俗是长期存在且广泛存在的,从前古典时代到后古典时代以及整个玛雅和奥尔梅克地区。 We can imagine ancient viewers scouring artworks in search of these visual puns expressed, for example, in the subtle shift of a musician's hand playing a trumpet, a wounded warrior falling to the ground in a gradual state of undress, a powerful noble gesticulating to his court, or the elaborate dressing of a lord.我们可以想象古代观看者在搜寻艺术品时寻找这些视觉双关语,例如,音乐家弹奏小号的手的微妙变化,受伤的战士以脱衣服的状态跌落在地上,强大的贵族象征着他法院或精心修饰的主人。

我们对Bonampak壁画的讨论分为四个部分:

- Bonampak的三个门

2.三个Bonampak房间和今天的隐喻

3.在每个“房屋”的屋顶上放置了三个邦纳帕克神:

玛雅人的时间之神

a.一种。 The eastern room: dawn, beginnings and creation东方室:黎明,开始和创造

b。 The western room: the end of days and sowing西洋房:天涯和播种

C。 The central room: life-is-a-battle metaphor中央房间:人生是一场战斗的隐喻

4。 结论

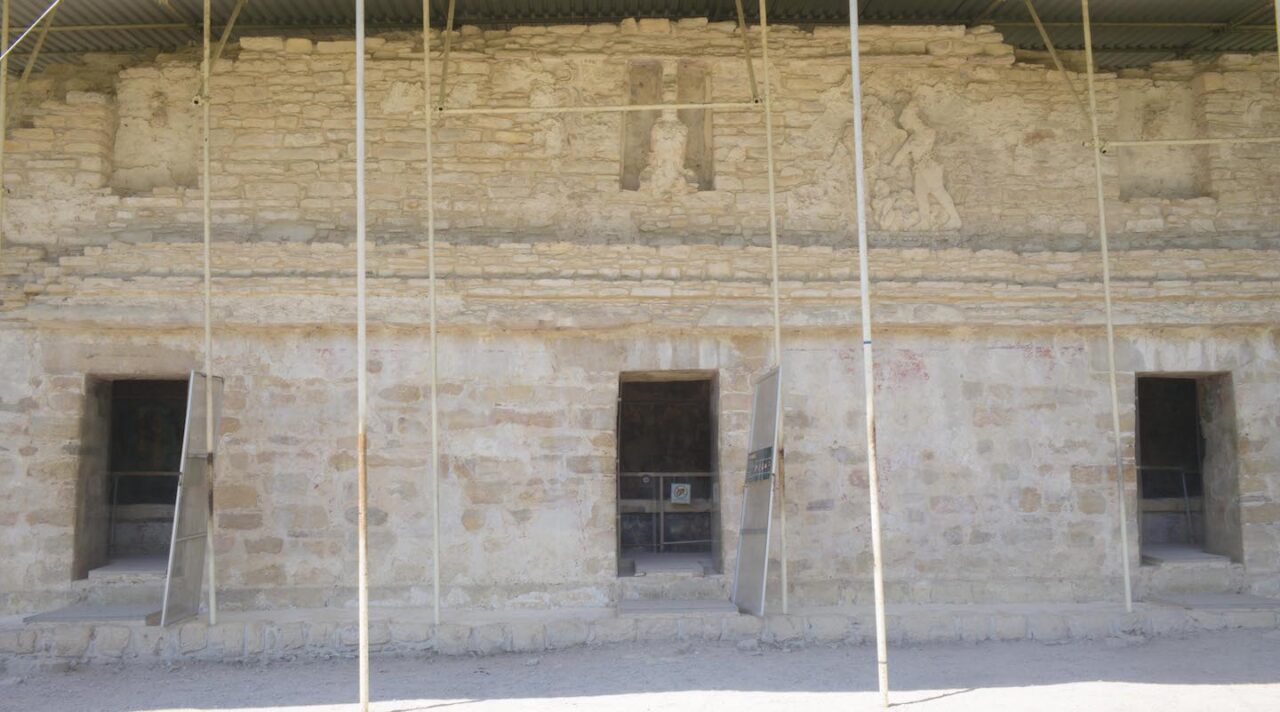

Bonampak的三个门

A1。 经典时期Bonampak门Lin 1至3的细节,在其底侧进行雕刻和绘画,并支撑通向结构1的三个门道(请参阅F1,从左至右)。 为了吸收艺术品的总和,观众必须在三个门之间行走。 拼凑在一起,该序列使被他的头发抓住的俘虏的长矛生气蓬勃。

Bonampak Lintel序列(1到3)拼凑在一起,动画化了被他的头发抓住的俘虏的长矛。 门横跨通往结构1的三个门廊中的每一个,并在其下侧雕刻有图像,图像要求观看者移动,在房间之间躲避以触发其动画内容。 第一和第二石之间的变化是微妙的,然后从第二到第三石的变化更大。 不同的时间间隔表示特定的模式,这是在Maya动画中经常重复使用的视觉设备,以建立预期。 最初的变化是缓慢的,然后是突然的,就像一个看好的锅似乎从未沸腾一样。

Bonampak门lin揭示了广泛的玛雅哲学,将他们的艺术品和石碑三联画与人类条件结合在一起。 门lin上描绘的三个不同的人物最初是作为一个人执行的单个动作:首先,显示该人物抓住一个畏缩的受害者的头发(Lintel 1),然后将他的长矛(Lintel 2)浸入,然后举起再次刺穿俯卧的俘虏(Lintel 3)。 观看这三个门each需要平卧的姿势,因为只有躺下并抬头看图像,观看者才能身体上假定受害者的姿势,如上面的战士所示。 尽管the石文字显示了三名战士的身份是按时间分隔的不同精英人物(请参见Miller and Brittenham 2013:30,65-68),但它们在反复发生的事件中表现出共同的表现(例如俘虏),尽管从未准确地重复出现过,但它代表了重复的人类行为。 尽管三个石在时间上分别属于不同的主角(日期分别为公元12年787月1日[Lintel 8],公元787年2月16日[Lintel 748]和AD 3年2013月30日[Lintel 65];请参见Miller和Brittenham 68:1,1-787,表2),三联画的运动流程显示了一个将周期性历史事件联系在一起的单一时间动作。 Lintel 1描绘了Bonampak统治者Yajaw Chan Muwaan在公元3年俘虏了他的受害者; Lintel 748代表当代Yaxchilan统治者Shield Jaguar IV,他的俘虏在Lintel 2013上的日期所描述的事件发生前四天。 有人建议说,Lintel 65可能是Yajaw Chan Muwaan的父亲早在公元1979年杀死了他的敌人(Miller和Brittenham XNUMX:XNUMX)。 因此,通过记录重复事件,古代玛雅人证明了周期性重现的观念(请参阅Trompf XNUMX),在这种情况下,随着时间的推移反复出现的反复行为在我们的生活和我们生活的周围世界中构筑了结构。 古代玛雅人在这个结构上施加了三重结构。

门还评论了邦纳帕克(Bonampak)和雅克希兰(Yaxchilan)这两个遗址的交织政治,以及政治路线的周期性延续或重生: 西 lintel is mirrored by his son depicted on the east lintel.门lin被他的儿子描绘在东门tel上。 As the father's reign sets like the sun on the western lintel, his line is reenergised and he is reborn like the dawn sun through his son on the east lintel.父亲的统治像西石上的太阳一样落下,他的线条重新焕发活力,他像儿子从东east石上的黎明太阳一样重生。 Furthermore, the father-son pair frame the Yaxchilan ruler Shield Jaguar IV to form a politicaltriumvirate.此外,父子俩组成了亚奇基兰统治者希尔德·捷豹四世,形成了政治上的胜利者。 The Maya believed that 'governance in three' provided stability of rule, in the same way that the three legs of a ceramic, or the three stones around a hearth, stabilise the bowl or cooking pot that rests atop (see John 2018:92).玛雅人认为,``三分法治''可以提供统治的稳定性,就像陶瓷的三腿或炉膛周围的三块石头可以稳定放在上面的碗或烹饪锅一样(见约翰XNUMX:XNUMX) 。 This triadic这个三合会 稳定性 被连接平衡 运动 一场长枪罢工,其中三名球员合而为一。

这样,重复重要的生活和仪式事件(例如出生,死亡,婚姻或打球)和亵渎的日常活动(例如三石壁炉的日光照明,使用三足的玉米研磨) 马诺 和 metate,房屋扫地或照料房屋的运动 米邦塔)创造一个存在的节奏,其内容随时间和历史由不同的人播放(约翰2018:99-100)。

Similarly, the Maya structured their stories and the motion of their accounts, which were once 'housed' within their books, in 'three'.同样,玛雅人以“三个”来组织他们的故事和帐户的动向,这些故事和帐户的动议曾经被“安置”在他们的书中。 The的 Popol Wuj creation account is recorded in the three tenses – past, present and future (see Tedlock 1996:63-74, 160-163, 221 [note 64]) – and the entire book is divided into three sections: including a description of the creation of the earth and its inhabitants, the story of the Hero Twins and their father and uncle and, finally, an account of the founding of the three K'iche' dynasties (Christenson 2007; Tedlock 1996).创作帐户以过去,现在和未来三个时态记录(请参见Tedlock XNUMX:XNUMX-XNUMX、XNUMX-XNUMX、XNUMX [注释XNUMX]),整本书分为三个部分:包括对创作的描述关于地球及其居民的故事,其中包括“双胞胎英雄”及其父亲和叔叔的故事,最后讲述了三个基切王朝的建立(Christenson XNUMX; Tedlock XNUMX)。 The Maya also favoured triptych groupings of stelae, lintels and painted mural programmes.玛雅人也喜欢石碑,门和彩绘壁画节目的三联画组合。 For example, the three lintels at Yaxchilan and the three painted Bonampak rooms 'tell' a tale.例如,Yaxchilan的三只门和Bonampak的三间彩绘房“讲述”了一个故事。 It seems that we compose a story from individual memories in the same way that threads are woven or counted to make a看来,我们是根据个人记忆中的故事来编造故事的,就像编织或计数线来构成一个故事一样。 huipil by remembering these memories or patterns, respectively.分别记住这些记忆或模式。 In considering this we arrive at an often-revisited existential question, linking time to our own story ('What is?') and the deterministic thought surrounding the natural extent of fate ('What is possible?'):考虑到这一点,我们得出了一个经常被重访的存在性问题,将时间与我们自己的故事(“什么是?”)和围绕命运的自然范围的确定性思想(“什么是可能的?”)联系起来:

Had Pyrrhus not fallen by a beldam's hand in Argos, or Julius Caesar not been knifed to death.如果Pyrrhus没被贝尔格达姆的手摔倒在Argos,或者Julius Caesar没有被刀杀死。 They are not to be thought away.不容忽视。 Time has branded them and fettered they are lodged in the room of the infinite possibilities they have ousted.时间给他们烙上了烙印,并束缚着他们被驱逐出无限可能性的房间。 But can those have been possible seeing that they never were?但是那些人有可能看到他们从来没有过吗? Or was that only possible seeing that they never were?还是只有看到他们从来没有出现过? Or was that only possible which came to pass?还是唯一可能实现的可能性? Weave, weaver of the wind.编织,编织风。 Tell us a story, sir先生,告诉我们一个故事

(Joyce 1986:第2章/第48-54行)。

At Bonampak, in order to absorb the entire mural sequence, the viewer is required to walk between three rooms, halting, to then pivot about their own axis within each room.在Bonampak,为了吸收整个壁画序列,要求观看者在三个房间之间行走,停下来,然后在每个房间内围绕自己的轴旋转。 Our own motion of viewing the three mural rooms links in with the paradox of time, each of us bringing a unique performance to the viewing of their images.我们自己观看三个壁画室的动作与时间的悖论联系在一起,我们每个人都为观看其图像带来了独特的表现。 Thus, our motion, subtle in its variation, is juxtaposed by the stability of the structure walls canvasing the murals, highlighting motion versus stability.因此,我们的运动(其变化微妙)与布满壁画的结构墙的稳定性并列,突出了运动与稳定性。

To this day, millions of visitors to Maya archaeological sites unwittingly perform the same performance and ritual walking linking circular time, 'three' and animation.时至今日,数以百万计的玛雅考古遗址游客在不知不觉中都进行了相同的表演和仪式行走,将循环时间,“三个”和动画联系在一起。 For example, when visiting Chichen Itza and walking between the 'rooms' of the three famous structures – the Castillo, Ball Court and Temple of the Thousand Columns – to complete the tour, we may experience how each of these was subjected by the Maya to the structure of three-part time (see John 2018:111-221).例如,在参观奇琴伊察并在三个著名建筑的“房间”之间(卡斯蒂略,球形球场和千柱庙)走来完成游览时,我们可能会体验到玛雅人如何分别对它们进行处理。三部分时间的结构(请参见John XNUMX:XNUMX-XNUMX)。 As visitors to ancient sites, walking between the three Bonampak rooms, we therefore replicate the past motion of the ancient Maya, whose ritual footsteps we are now once again enabled to imagine because the symbolic significance of this motion is finally understood.作为参观古代遗址的游客,我们在三个Bonampak厅之间行走,因此我们复制了古代玛雅人的过去动作,现在我们再次能够想象其古老的玛雅仪式,因为这一动作的象征意义得以最终理解。 Our motion is what activates and completes the artwork, as we, the viewer, become part of the duality of time.当我们(观众)成为时间二重性的一部分时,我们的动作便激活并完成了艺术品。

三个Bonampak房间和今天的隐喻

Bonampak的观众要求激活三幅壁画室之间的走动动作以激活艺术品,这直接与一个古老的中美洲概念有关,即当今的隐喻。 许多玛雅人的信仰都集中在人类对一个“天”的体验上,这一天使时间和地点,白天和黑夜,神圣和亵渎相融合(Earle 2000:72)。

将一个人的命运与一天相提并论……死亡就像夕阳一样……[他们会]恳求灵魂不让自己的一天缩短

(Earle 2000:100,作者的括号)。

A three-part rhythm structured day, year and life 'time' metaphors of the men who worked the fields, toiling beneath the sun.由三个部分组成的节奏构成了在田野里工作,在阳光下劳作的人的日,年和生命“时间”的隐喻。 Earle (2000:80-81) records the movement of K'iche' men walking from their home to the field and back again, returning to the cool of the house at noon, being tied to a three-part rhythm;厄尔(Earle,XNUMX:XNUMX-XNUMX)记录了凯奇(K'iche')的人从家中走到田野并再次返回的运动,中午回到房子的凉爽处,这与三部分的节奏息息相关。 the men's agricultural chores, furthermore, changed throughout the year to match the seasons, in that they corresponded with, or were joined to, the changing motion of the sun in its relation to the horizon.此外,男子的农业杂务全年都会变化以适应季节,因为它们与太阳相对于地平线的变化运动相对应或相关联。

This process in the cosmos has its earthly counterpart in human activities.宇宙中的这一过程在人类活动中与世俗相对。 The wife wakes in the predawn chill and brings the hearth fire back to life from the coals of the previous night.妻子在黎明前的寒冷中苏醒,并从前一天的煤中将炉膛火带回了生活。 The women begin to grind the kernels that have cooked all night on the grinding stones and slap the tortillas together, as the men rise with the sun.当男人随着太阳升起时,女人开始在磨石上磨碎整夜煮熟的玉米粒,然后将玉米饼拍打在一起。 After a light breakfast, the men warm themselves and leave for the fields… and begin to work the land with their broad hoes… the men return home to eat the noon meal [Before returning to the field].享用了少量早餐后,这些人取暖并离开田野……并开始用宽阔的ho头在土地上耕作…………[回到田野之前]这些人回到家中饱餐。

As the sun wanes in the afternoon… the men return home… men are like the sun… The adult man's active role is one that follows a pattern of cyclical increase and decrease in heat as the day transpires.随着下午太阳的减弱,男人们回到家园……男人们就像太阳一样……成年男子的积极角色是,随着一天的蒸腾,热量的周期性增加和减少。 The women, on the other hand, remain predominately around the dark and unchanging house and canyon, insulated from the sun.另一方面,女性则主要呆在黑暗和不变的房屋和峡谷周围,与阳光隔绝。 Their work is constant, unchanging from day to day, season to season, regardless of the time they must keep the house swept, the water jar full, the children fed, and the food attended to.他们的工作是恒定不变的,每天,每个季节都保持不变,无论他们何时必须打扫房屋,盛满水的罐子,给孩子喂食以及照看食物。 Thus, a complimentary opposition of male cyclical and female constant action is in the day cycle analogous to daytime and night or, alternatively, sun and earth因此,类似于白天和黑夜,或者太阳和地球,白天周期中男性周期性和女性恒定行为的互补性反对

(Earle 2000:78-79,作者的括号)。

在三个Bonampak壁画室之间走来走去,就再现了这种农业真理,表达了为既定事物赋予某种事物的观念。 为了生存,必须死亡。 如今的隐喻背后的哲学也揭示了壁画中男性的主要表现形式。 男人像太阳一样,一天又一天消逝,而女人则很少被描绘在壁画的“房屋”中。

对女性世界的一瞥,使我们想起法院还有另一个方面,通常是看不见的

(Miller and Brittenham 2013:84)。

An explanation for the comparative lack of females represented in the murals may be that they represent the unchanging constant, the night or earth, seen as forming part of the metaphor of the day.壁画中女性相对缺乏的一种解释可能是,它们代表着不变的常数,即夜晚或地球,被视为白天隐喻的一部分。 Consequently, the overall symbolism of the murals most simply relates to the duality of time, the metaphor of the day providing a Maya explanation of the rhythm of life.因此,壁画的整体象征意义最简单地与时间的二元性有关,白天的隐喻提供了玛雅人对生活节奏的解释。

F2。 Bonampak结构1在其三个房间中放置壁画。

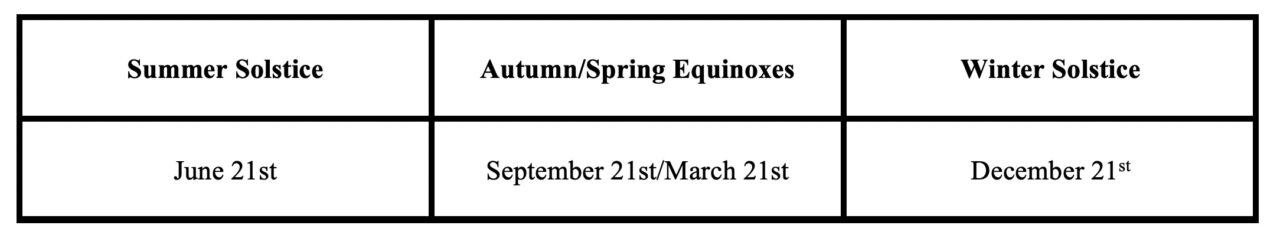

由于他们的日历轮次和长期计数都与季节没有保持一致的联系,因此玛雅人还设计了与太阳相关的日历, 哈布。 They noticed that the sun passed or 'interacted' with the horizon in a recurrent seasonal troika.他们注意到太阳以周期性的三驾马车从地平线上掠过或“相互作用”。

…那条曲线形成了天空中的金色秋千。

(Calasso 1993:41)

哈布 创造了一种节奏,通过相对于三个点的运动将太阳与一年结构性地联系起来:秋分和春分,发生在中间的同一“点”,冬至夏至, 转折点 点两边。

Consequently, it appears that the Maya charted the movement of the sun in relation to the horizon.因此,玛雅人似乎绘制了太阳相对于地平线的运动图。 This interaction between the sun and the horizon was emphasised through the use of three points or 'markers', such as groups of three stone structures, to link three (stone structures) to time through the movement of the sun and the temporal rhythm of the year.通过使用三个点或“标记”(例如由三个石头结构组成的组)来强调太阳与地平线之间的这种相互作用,以通过太阳的运动和太阳的时间节奏将三个(石头结构)与时间联系起来。年。 Such giant stone structures occur, for example, at Uaxactun (Early Classic Group E), Caracol (A-Group, Structure 6; a large这种巨大的石头结构出现在例如Uaxactun(E早期经典组),Caracol(A组,结构XNUMX;大型 AHAW stone altar was placed at the viewing point atop western Structure A2), Calakmul (see Folan et al. 1995:315, fig. 4) and Tikal (Structure 5C-54, the 'Lost World Pyramid').石坛放置在西部结构AXNUMX,卡拉克穆尔(参见Folan等人XNUMX:XNUMX,图XNUMX)和蒂卡尔(XNUMXC-XNUMX结构,“失落的世界金字塔”)上方的观察点上。 Time was seen to move the sun between these three points and its three-part structure.人们看到时间使太阳在这三个点及其三部分结构之间移动。

The triadicmovement of the sun in relation to the Maya solar year ties in with the politico-agricultural theme of maize running through the murals.太阳相对于Maya太阳年的三重运动与壁画中玉米的政治农业主题有关。 Since antiquity, the longest day of the year has been celebrated across the world in association with the beginning of harvest and the turning point of the year towards darkness, while the winter solstice represents the opposite, with descent ending and renewed reascent beginning, linked to chthonic themes, sowing and resting.自上古以来,世界上每年的最长一天与收获的开始和一年中朝向黑暗的转折点相关联,而冬至则相反,下降的结束和重新开始的重新开始与chthonic主题,播种和休息。 The solar rotation of ascension and degradation thus unites light and darkness.太阳的上升和退化的旋转因此将光明与黑暗结合在一起。 While the viewer moving between the Bonampak mural rooms now becomes comparable to the 'golden swing in the sky', moving like the sun between the seasons.现在,当观看者在Bonampak壁画室之间移动时,就变得可以与“空中的金色秋千”相提并论了,每个季节之间就像太阳一样移动。

Bonampak的三个神在装饰每个“房屋”的屋顶:

时间的玛雅众神

现在,我们来讨论装饰三个Bonampak房间中每个房间的穹顶的三位一体神。 如果我们接受这些房间中的每一个都构成一个微型“房子”,并且这些房子被用作世界的微型模型,那么我们可以推断出,其穹顶中所代表的众神位于天空中,以雨,雷声为主题和闪电似乎最合适。 我们建议他们代表三位一体的神灵,每个神灵都体现出时间圈的一个方面-出生,成长和死亡。

在玛雅宇宙学中,神三位一体的观念非常古老(Christenson 2007:71 [脚注65])。 古代世界的多种文化中也存在着类似的宗教三合会概念。 我们认为,三位一体的概念(与宇宙炉缸相关)适用于所有中美洲文化,每种文化在形式上都表现出区域性差异,例如,特奥蒂瓦坎三位一体(参见Headrick 2007:104-11),帕伦克三合会(GI,GII,GIII)和三个雷电神 Popol Wuj.

Studying the animations hidden in ancient Maya artworks has led us to propose that this trinity of gods includes Chaahk (responsible for Sowing), Ux Yop Huun (for Life) and K'awiil (for Birth);通过研究玛雅古代艺术品中隐藏的动画,我们提出了三位一体的神灵:Chaahk(负责播种),Ux Yop Huun(负责生命)和K'awiil(负责出生)。 they are comparable to the Hindu Trimurti Shiva (considered the Destroyer), Vishnu (the Preserver) and Brajma (the Creator), creating a conceptual link between ancient Asia and the Americas.它们可与印度教徒Trimurti Shiva(被视为毁灭者),Vishnu(保存者)和Brajma(创造者)相媲美,从而在古代亚洲和美洲之间建立了概念上的联系。

Thunder and lightning gods in other ancient cultures were perceived as powerful and omnipotent beings that could cause either death and destruction, or fertility and new life, such as Thor, Zeus and Indra.在其他古代文化中,雷神和闪电神被认为是强大而无所不能的生物,它们可能导致死亡和毁灭,生育和新生命,例如托尔,宙斯和因陀罗。 The conceptual origin of thunderstorms causing destruction leading to fertility is deeply entrenched in our human experience of nature, where violent thunderstorms precede spring rains that reawaken the divine life forces (Wilhelm 1950:298).雷暴引起破坏并导致生育的概念性根源深深植根于人类对自然的体验中,在这里,猛烈的雷暴在春雨来临之前重新唤醒了神圣的生命力量(Wilhelm 1993:139)。 This is also true in Mesoamerica, where thunder is linked to sound, and lightning itself was seen as a manifestation of powerful fertilising energy, as, for example, recorded in the myth of the origin of maize when lightning split open the rock containing the hidden seed (Freidel et al. 140:281-XNUMX, XNUMX).在中美洲也是如此,雷声与声音联系在一起,闪电本身被视为强大的施肥能量的体现,例如,当闪电劈开包含隐藏物的岩石时,在玉米起源神话中就记载了这一点。种子(Freidel et al。XNUMX:XNUMX-XNUMX,XNUMX)。

[三]石炉膛散发出野生八角的浓烟,长笛的音乐带来了上帝的思想

(Asturias 2011:49,作者的括号)。

Sound and music go hand-in-hand with religious ceremonies conducted throughout the world, the noise evoking primal emotions.声音和音乐与在世界各地举行的宗教仪式齐头并进,噪音唤起了原始情感。 While the sound described by the Guatemalan Nobel Laureate Asturias brings thoughts of gods, we suggest that the three Maya Gods of Time were linked to the noise of thunder, and were related to the three 'Thunderbolt' deities listed in the虽然危地马拉诺贝尔奖获得者阿斯图里亚斯描述的声音带来了众神的思想,但我们建议时光的三个玛雅神灵与雷声有关,并且与列在其中的三个“霹雳”神灵有关。 Popol Wuj creation account (see Christenson 2007:70-73 and Tedlock 1996:63-66);创造账户(参见Christenson XNUMX:XNUMX-XNUMX和Tedlock XNUMX:XNUMX-XNUMX); these time gods were, moreover, associated with sound:而且,这些时候,神与声音联系在一起:

First is Thunderbolt Huracan, second is Youngest Thunderbolt, and third is Sudden Thunderbolt.第一个是Thunderbolt Huracan,第二个是Youngest Thunderbolt,第三个是Sudden Thunderbolt。 These three together are Heart of Sky.这三个是天空之心。 They came together with Sovereign and Quetzal Serpent.他们与君主和格查尔蛇一起来到了这里。 Together they conceived light and life他们在一起构想了光与生活

(在Christenson 2007:70中)。

与其他创建帐户不同,以上内容 Popol Wuj passage does not appear at first glance to make a clear reference to the three-stone setting of time.乍一看似乎并没有清楚地指出三段时间的设定。 However, closer inspection reveals the event encrypted within the text.但是,仔细检查会发现该事件在文本内已加密。 The choice of words used to describe the birth of life reinforces the idea that the genesis of three-part time formed the vital moment of creation.用来描述生命诞生的词语选择强化了这样一种观念,即三部分时间的起源是创造生命的关键时刻。 We propose that the concept of time (including sound and stone) is incorporated within the three 'Thunderbolt' god names listed in the passage.我们建议将时间(包括声音和石头)的概念纳入段落中列出的三个“雷电”神名中。

Similarly, we propose that 'Thunderbolt' forms a poetic reference to what separates and yet binds the two words;同样,我们建议“雷电”对分离但仍约束两个词形成诗意的参考。 that is, thunder-lightning, which expresses the broader concept of time.即雷电,代表了更广泛的时间概念。 As all the three Time Gods receive this title in the由于所有三个时间之神在 波波尔·乌,因此这三个必须与更广泛的时间概念相关,同时也暗示了遗传关系。

该作者 Popol Wuj text chose to construct the word 'thunder-bolt' by combining the elements of two separate events.文本选择通过组合两个单独事件的元素来构造“雷电”一词。 He juxtaposed the delayed sound of thunder rumbling with the flash of lightning.他将雷鸣般的延迟声与闪电声并列。 Consider how, when we see a flash of lightning, we instinctively begin to count.考虑一下,当我们看到闪电时,本能地开始计数。 This reflex represents an ingrained anthropological trait enabling us to identify the centre and relative direction of storms to ensure our safety.这种反射代表着根深蒂固的人类学特征,使我们能够确定风暴的中心和相对方向,以确保我们的安全。 Our suggestion is that the words chosen to form the 'Thunderbolt' title conceptualise the time elapsed between seeing a lightning bolt strike and hearing its delayed thunder, the clap.我们的建议是,选择构成“ Thunderbolt”头衔的词语会概念化表示从看到雷击到听到雷鸣声之间的时间间隔。 As explained above, this literary construct is called a merismus.如上所述,这种文学构架被称为“ merismus”。

……还有天上的心,据说这是上帝的名字。 Then came his word.然后他的话来了。 Heart of Sky arrived here with Sovereign and Quetzal Serpent.天空之心与君主和格查尔毒蛇一起来到了这里。 They talked together then.他们一起聊了起来。 They thought and they pondered.他们想了想。 They reached an accord, bringing together their words and their thoughts.他们达成了协议,将他们的言论和思想汇聚在一起。 Then they gave birth, heartening one another.然后他们生了孩子,彼此鼓舞。 Beneath the light, they gave birth to humanity.在光明之下,他们孕育了人类。 Then they arranged for the germination and creation of the trees and the bushes, the germination of all life and creation, in the darkness and in the night, by Heart of Sky, who is called Huracan然后,他们安排了被称为Huracan的天空之心在黑暗和夜晚中进行树木和灌木丛的发芽和创造,所有生命和创造的发芽。

(在Christenson 2007:70中)。

赫拉坎的名字克里斯滕森(2007:70 [脚注62])将天空之心解释为“飓风之眼,形成了神圣的轴心,时间和创造物围绕着这根神轴在无休止的重复性出生和破坏循环中旋转”。 这三个雷电神灵共同构成了天空之心,时光之ura,风,闪电和雷电的旋转轴心。 谐音词huracán可能指强旋风,而现代英语单词hurricane可能源自Taino版本的该词 乌拉坎 (Christenson 2007:70 [脚注62])。

我们与K'awiil关联的雷电神灵包含 朱拉干 以他的玛雅名字 朱拉干 翻译为“一条腿”, 拉q 可能是指闪电或长时间闪烁。 Christenson(2007:70 [脚注62])使得“单足神”卡维伊(帕伦克三合会的神II,经常被描绘成一只拟人化的脚而另一只腿被描绘成蛇)之间的联系又越来越多。 K'iche'可能会将“腿”用作计数有生命的事物的方式,就像计数牛时提到“头”一样,并且 拉q 至 测量 去除物体的长度或高度(Christenson 2007:70 [脚注62])。 这些联系提供了证据,证明凯维与时间计数和时间测量有关。

We can imagine how measuring out would have formed an important part of creating a Maya artwork;我们可以想象,测量出的尺寸将如何构成Maya艺术品的重要组成部分; whether on the curved surface of a ceramic, or a long mural wall, artists would have used cord and paper templates to create and space out the animations we have detected.无论是在陶瓷的弯曲表面上,还是在长壁画墙上,艺术家都将使用绳和纸模板来创建和隔开我们检测到的动画。 We know that the murals were measured out upon the template of a grid (Miller and Brittenham 2013:13-20), with the motional tempo of the murals superimposed onto this structured frame of time.我们知道壁画是在网格模板上进行测量的(Miller和Brittenham XNUMX:XNUMX-XNUMX),壁画的运动节奏叠加在这个结构化的时间框架上。 In this way, Maya artists mimicked the gods' design of the time-space of the world.通过这种方式,玛雅人的艺术家模仿了神对世界时空的设计。

A further element strengthening the association of the literary construct 'Thunderbolt' with 'time' may be found in the divination capacity of a Maya shaman.在Maya萨满巫师的占卜能力中,可以发现进一步加强文学构造“雷电”与“时间”的关联的元素。 Known to this day as迄今称为 aj q'ij,他们被认为是血液中的闪电(Christenson 2003:201),并被认为具有超越时间和距离限制的能力。 As music frequently accompanied acts of divination (Looper 2009:58), it is possible that music and sound were also related to future-time.音乐经常伴随着占卜行为(Looper XNUMX:XNUMX),所以音乐和声音也可能与未来有关。

在玛雅语中,“雷声”翻译为 基林巴尔山鹰 和闪电作为 莱莱姆查克 (Conde 2002:104和60)。 Furthermore, Mayan words for thunder and lightning bolt include references to the name of the deity Chaahk, here proposed as forming one of the three Time Gods.此外,玛雅语中的雷电击中还提到了查阿克(Chaahk)神的名字,这里被提议构成三位时代神之一。

We also propose that the deities' names and connection refer to the associated time between the flash of lightning and the sound of thunder.我们还建议神灵的名字和联系是指闪电和雷声之间的相关时间。 Completing this circle of association, it seems that the connection the Maya saw between stone (as time) and sound carried great cultural complexity and depth.完成这一交往圈后,玛雅人看到的石头(作为时间)与声音之间的联系似乎带有极大的文化复杂性和深度。 We found evidence of this association persisting to this day while travelling across the Yucatan peninsula at the end of the dry season.我们发现,在旱季结束时穿越尤卡坦半岛旅行时,这种联系一直持续到今天。 Staying in a small village near the archaeological site of Ek Balam, our meal was interrupted by the first great storm of the rainy season.住在Ek Balam考古遗址附近的一个小村庄,我们的用餐被雨季的第一次大风暴打断了。 Our Maya host began to count out aloud immediately after the first lightning flash, shouting 'Chaahk' as soon as she heard the thunder crack, all the while gesturing up to the sky.我们的玛雅人主持人在第一次闪电过后立即开始大声地数着,一听到雷声就喊着“ Chaahk”,一直到天空。 She was thus associating the count of time with sound and one of the Maya Gods of Time.因此,她将时间与声音和玛雅时间之神之一相关联。 The next morning revealed the destruction wrought by the storm, which would contrast with the future birth of crops ensured by its rain.第二天早晨揭示了暴风雨造成的破坏,这与雨水确保未来农作物的生长形成了鲜明对比。

在科尔特斯和阿兹台克皇帝穆克图祖玛之间进行的对话中,我们还发现了雷电的弯月面作为历史时间的参考:

It is true that I [Moctezuma] am a great king, and have inherited the riches of my ancestors, but the lies and non-sense you have heard of us are not true.我确实是一位伟大的国王,已经继承了我祖先的财富,但您听到的关于我们的谎言和胡说是不正确的。 You must take them as a joke, as I take the story of your thunders and lightnings [read times or histories]您必须以他们为笑话,就像我以您的雷电故事[阅读时间或历史]

(DíazdelCastillo 1963:224,作者的括号)。

Further evidence linking the Thunder-and-Lightning Gods to time may be found among the contemporary Maya.在当代玛雅人中可以找到将雷电之神与时间联系起来的进一步证据。 These Maya distinguish between vigorous and youthful lightning gods and gods of thunder, usually aged gods of the earth and mountains (Miller and Taube 1997:107).这些玛雅人将充满活力和年轻的闪电神和雷电神区分开,通常是大地和山区的古老神(Miller and Taube XNUMX:XNUMX)。 The same is true of the modern Huatec Maya of Northern Veracruz (ibid), which suggests a broadly established Mesoamerican perception of a temporal lapse existing between the flash of lightning (equated with youth) and thunder (as aged time).北韦拉克鲁斯州的现代瓦特玛雅人(同上)也是如此,这表明中美洲人对雷电(等同于青年)和雷声(随年龄增长)之间存在的时间流逝的认知已广为人知。

三个神灵中的每一个都包含在三个Bonampak房间的单独讨论中,以展示它们的壁画如何支持东方(与K'awiil有关),西方(与Chaahk有关)终结于西方的周期性起点的思想。与终生成长主题相关的最大,最中心的房间(与Ux Yop Huun相关):它们是三个时代之神。

三个时间神及其相关房间的出现顺序与它们在创世期间的出现顺序相对应,如 Popol Wuj and in other creation accounts (such as on the Vase of the Seven Gods and in the Santa Rita Murals; John 2918:188-195).以及其他创世记述(例如《七神之瓶》和《圣丽塔壁画》;约翰福音XNUMX:XNUMX-XNUMX)。 They represent the three steps initiating, and then supporting, the never-ending flow of time, by propelling the sun along its cyclical solar path, which involved its birth, ascent (or growth) and descent in relation to the world;它们代表着太阳沿着其周期性的太阳路径推进,然后支撑着无休止的时间流逝的三个步骤,这涉及到太阳的诞生,上升(或生长)和相对于世界的下降。 the three gods represent the gods of cyclical renewal, or more simply put, the Maya Gods of Time.这三个神代表了周期性更新的神,或更简单地说,就是玛雅时间神。

We have recently spent our time recreating the animations, presented below, ubiquitous in the Bonampak murals.最近,我们花费了很多时间来重新制作下面介绍的Bonampak壁画中无所不在的动画。 The following sections approach the murals with the worldview of cyclical time, a philosophy that would have been widespread and known by Maya elite and commoners alike.以下各节以周期时间的世界观来探讨壁画,这种哲学早已被玛雅精英和普通民众所广泛采用并广为人知。

东部房间:

黎明,开始和创造

东方厅1隐喻地表达了新的开始,出生和黎明的主题,由上方的穹顶中的K'awiil监督。 初始系列文本的大字形涂在隔开两个图形行的宽带中,确认此房间是“出生”的专用部分, 开始 of 次。 Miller and Brittenham write:米勒和布里顿纳姆写道:

…如果希望使用给定的“阅读顺序”…,那么几乎可以肯定从1号房间开始,其中包含冗长的《首创系列》文字,这是一种书写风格,预示着碑石,门lin和其他雕刻纪念碑上的铭文的开始……如果在彩绘的圆柱花瓶上,则从左到右的顺序可以是圆形的,但是它永远不会无止境; that is, it starts and stops, just as it does here也就是说,它开始和停止,就像在这里一样

(Miller and Brittenham 2013:64)

A new perspective on the conceptual association of the Initial Series text and its surrounding imagery requires the recognition of the use of metaphor in Maya art.有关“初始系列”文本及其周围图像在概念上的关联的新观点,要求人们认识到玛雅艺术中隐喻的使用。 The start of the Initial Series text and the literal初始系列文本和文字的开头 数 of time is accompanied by the music of a band depicted on the east wall below, whose animated beat keeps time with the progression of the text;时间的流逝伴随着下方东墙上描绘的一支乐队的音乐,其动感的节拍使时间随着文字的进行而保持同步; in fact, the image pairing forms an excellent example of the conceptual association the Maya placed between time and sound.实际上,图像配对是Maya在时间和声音之间放置的概念关联的一个很好的例子。 Simply put, the beat of music created by the band depicted forms a visual metaphor for the count of time.简而言之,乐队所描绘的音乐节拍形成了时间计数的视觉隐喻。

A2。 Bonampak East Room 1壁画细节。 2013(HF 113-212-51)。

A3。 游行音乐家颤抖的动画。 HF 60和61在附带的字形标题中描述为 卡约姆 或“歌手”(Miller和Brittenham 2013:81,图146),可能表示“他们开始唱歌”。 Bonampak East Room 1壁画细节(HFs 57-61)。

New importance is therefore injected into the measured 'tempo' with which the parading figures are spaced, the lower painted register of this eastern room now comparable to the steady beat of a drum, or the rhythmic shake of a rattle;因此,新的重要性被注入到间隔着游行人物的被测量的“节奏”中,这个东方房间的较低的彩绘现在相当于鼓的稳定拍子或拨浪鼓的有节奏的颤动。 at this 'beginning', time seemingly moves in a measured and predictable way.在这个“开始”阶段,时间似乎以可衡量且可预测的方式移动。 Furthermore, the temporal placing of the east and west wall figures conforms to an imperfect oppositional balance, a chiasmic composition (Miller and Brittenham 2013:68);此外,东墙和西墙人物在时间上的摆放符合不完美的对立平衡,即一种奇异的构图(Miller and Brittenham 72:56); consider how HF 2013 (west) and HF 72 (east) simultaneously turn their bodies against the flow of the parade to indicate a change in speed experienced by the viewer as a pausing or halting.考虑一下HF XNUMX(西侧)和HF XNUMX(东侧)如何同时将他们的身体逆着游行队伍的方向转动,以指示观看者由于暂停或暂停而经历的速度变化。 Likewise, Miller and Brittenham (XNUMX:XNUMX) note how the parasols stretching up from the lower tier frame the Initial Series text on either side 'like colourful quotation marks'.同样,Miller和Brittenham(XNUMX:XNUMX)指出,遮阳伞如何从较低层向上延伸,使“初始系列”文本的两侧“像彩色引号”。 We propose that the shape and colour of the large fans represents a visual metaphor for the sun and its movement, over time, from east to west.我们建议大型风扇的形状和颜色代表太阳及其从东到西随时间的运动的视觉隐喻。 The two eastern fan bearers are obscured from view, unlike their contralateral counterparts, who are animated to waft their fans up and down.与对侧同行者不同,这两个东部球迷持票人被遮蔽了,后者生气勃勃地上下挥动他们的球迷。 Consequently, the animation that is 'seen' is balanced by what is 'unseen', fulfilling the duality of time discussed above.因此,“可见”的动画与“看不见”的动画保持平衡,从而实现了上述时间的二重性。 The breeze generated by the fans both starts and terminates the Initial Series text, thus forming a further reference to the association of wind and time.风扇产生的微风既可以启动也可以终止“初始系列”文本,因此可以进一步参考风和时间的关系。

A4。 大风扇冷却的贵宾们的动作观看了皇家舞,并为宣布时间开始的“初始系列”文本定了帧。 风扇从橙色变为黄色。 在对侧墙上从黄色变为橙色。 Bonampak East Room 1详情(HFs 73-74)。

壁画中的视觉反射或奇异结构类似于壁画中的文学“反射”。 Popol Wuj 创建帐户(Christenson 2007:46-52)。 符号 reflection in Maya art, like its literary equivalent, is inverted and imperfect, comparable, for example, to the way reflections in water are distorted.就像其文学上的对等物一样,玛雅艺术中的倒影也是颠倒而又不完美的,例如,与水中倒影的扭曲方式相当。 The deity Unen K'awiil, God of Birth and Dawn, is frequently marked with a mirror on his forehead to underscore his 'creative reflection' (John 2018:171-187).出生和黎明之神神恩恩·卡维伊(Unen K'awiil)经常在额头上刻有镜子,以强调他的``创造性思考''(约翰XNUMX:XNUMX-XNUMX)。

“开始”主题还为“初始系列”文本的内容赋予了新的含义,建议该词提及日期为公元790年的Bonampak统治者加入事件,并记录在公元1年的Stela 776上在Yaxchilan的国王Shield Jaguar的监督下(Miller and Brittenham 2013:64)。 加入计划与当时玛雅地区可见的日全食相吻合(公元790年XNUMX月;同上)。

The Initial Series text also describes the erection of a god effigy associated with the east, the colour red forming part of its unusually-long Lunar Series text, and a house-dedication ceremony involving 'fire-entering', all timed after a solar eclipse (Miller and Brittenham 2013:71-72).初始系列文字还描述了与东方相关的神像的竖立,红色是其异常长的农历系列文字的一部分,以及涉及“进火”的房屋奉献仪式,都在日食过后计时(Miller and Brittenham XNUMX:XNUMX-XNUMX)。 Consequently, in addition to announcing the beginning of the count of time, the content of the Initial Series text also echoes themes surrounding new beginnings in the east: the erection or setting up of a deity linked to the east, the colour red, associated with the east, an accession, likely considered a form of being 'born' to the throne and the responsibilities this entailed, and the entering or starting of a new fire in a house-dedication ceremony – all timed with a total solar eclipse that was likely seen as a cyclically-returning rebirth of the sun.因此,除了宣布时间的开始之外,“初始系列”文本的内容还呼应围绕东方新起点的主题:竖立或建立与东方有关的神灵,红色与在东部,可能是被视为“出生”于王位的形式及其所承担的责任,以及在房屋奉献仪式中新火的发生或起火,所有这些都与日全食有关。被视为太阳的周期性重生。 The text thus supports the idea that the eastern room was considered a 'house of dawn', overseen by K'awiil, the God of Dawn and Birth, whose forehead flare symbolised the fire or new light (lightning strike) entering the 'house'.因此,案文支持以下观点:东部房间被认为是“黎明之屋”,由黎明和出生之神卡维伊(K'awiil)监督,其前额耀斑象征着火或新光(雷击)进入“房屋”。 。

Unlike the Initial Series text that moves from left to right – from the east to the south to the west walls – the parading figure rows beneath converge from the east and west walls on the south wall and the first scene encountered on entering the room [F3].与从左到右-从东到南再到西墙的“初始系列”文字不同,下方的游行人物行从南墙的东墙和西墙汇聚,进入房间时遇到的第一个场景[FXNUMX ]。 Here,这里, 三 年轻的贵族, 乔克斯, literally meaning 'sprouts' (Houston 2009), are depicted dancing centre stage.在舞蹈的中心舞台上刻画了“豆芽”的字面意思(休斯顿,XNUMX年)。 Even though the three young dancers have been defaced, they originally undoubtedly formed an animation.即使这三个年轻的舞者都被污损了,他们最初无疑也形成了动画。 The artists cleared ample space surrounding their performance, where the viewer may imagine their swirling steps accompanied by loud music.艺术家们在表演周围留出了足够的空间,观众可以想象他们的旋涡步伐伴随着响亮的音乐。 Each每 ' 1号房中描绘的钻石还佩戴着K'awiil头上的玉冠和与珠宝相媲美的玉器,在K'inich Janaab Pakal国王在帕伦克的坟墓中发现过(Miller和Brittenham 2013:3)。 K'awiil王冠强调了与舞者表演相关的生育主题,而他们的翡翠首饰被认为有助于重生,因此经常被包括在墓葬中。

F3。 Bonampak东厅1,南墙壁画细节(HFs 26-27-28)。

关于1号房中的象征意义的建议与出生,更新和新起点的主题有关 新 maize throughout.整个玉米。 For example, on the north wall the例如,在北墙上 年轻 Maize God is painted sitting atop a turtle shell on the cylindrically shaped headdress of HF 42, who blows what is probably a whistle while shaking a rattle (see Miller and Brittenham 2013:118, fig. 224).玉米神被涂在HF XNUMX的圆柱形头饰上的海龟壳顶上,后者摇晃拨浪鼓的同时吹哨子(参见Miller and Brittenham XNUMX:XNUMX,图XNUMX)。 Beside him, two trumpet players – also named在他旁边,还有两个小号手-也叫 ' 在它们旁边绘制的字形中(Miller和Brittenham 2013:79)–动画化了当他们移动时 开始 发挥。

A5。 小号手移开手的位置开始演奏。 Bonampak Eastern Room 1壁画细节。 动画摘自Miller和Brittenham 2013:79,图。 137(HFs 43-44)。

爪子的敲击声和拍击声使乐队的音乐更加充实,这是HF 49所穿的巨型甲壳类动物服装的一部分–各种贝类主要在 开始 (Miller and Brittenham 2013:118-121)。 To the crustacean's right, a further beast, HF 50, holds a possible drum and large beating stick or hollow wind instrument.在甲壳动物的右边,另一只野兽HF 45可以容纳一个鼓和大型的打击棒或空心管乐器。 The seemingly haphazard arrangement of these fantastical beasts, HFs 50-XNUMX, is unique in its depiction in the three mural rooms, the beasts' masks indicating that they represent people performing a poignant moment within a play.这些奇幻的野兽,HFs XNUMX-XNUMX,看似随意的排列,在三个壁画房间中是独一无二的,这些野兽的面具表明它们代表了人们在戏剧中表现出凄美的时刻。 At the centre of the scene, the Wind God can be seen handing a green maize cob to在场景的中心,可以看到风神将绿色玉米芯交给 乌恩 卡维(新生Thunderbolt).霹雳)。 The exchanging of的交换 年轻 green maize by the two deities – comparable to passing a relay baton – signals the moment when seed is gifted;这两个神所发出的绿色玉米(相当于传递接力棒)标志着有天赋的时刻。 it represents the instant of germination and reiterates the birth theme running throughout the eastern murals.它代表了发芽的瞬间,并重申了贯穿整个东部壁画的出生主题。 A glyphic caption between the two deities reads两个神之间的字形标题为 巴兹扎姆 or 'head throne' (Houston 2008), possibly referring to the Maya's frequent equation of corn cobs with the head of the Maize God forming the fertile seed for future crops.或“头座”(休斯顿,XNUMX年),可能指的是玛雅人玉米穗轴的频繁方程式,其中玉米神的头形成了未来农作物的肥沃种子。 Here, the moment of creation occurs at the spatial point where two opposing flows converge, as the meeting of opposites, where the two gods face each other, like night meeting day.在这里,创造的时刻发生在两个对立的流汇合的空间点,作为对立的汇合,两个神在彼此对立的地方,就像夜晚的聚会日。 The scene probably occurs before the 'beginning', signalled by the Initial Series text, as a kind of cacophonous prelude announcing dawn.场景可能发生在“开始”之前,由“初始系列”文字表示,是一种发出黎明的刺耳的前奏。

F4。 Bonampak East Room 1壁画细节(HFs 45-46)。

A6。 动画化人类可能转变为鳄鱼兽的行为,以纪念神模拟者交换玉米(紧接其上,HF 45-46)标志着创造的时刻,这代表了未来重生的种子。 第一个人类演员的特征(HF 47)延续到野兽(HF 48)的特征中暗示了可能的转变,包括鳄鱼鳞片所重复的球茎绿领边缘,从其头饰生长的睡莲和鳄鱼。 动画摘自并改编自Miller和Brittenham 2013:79,图。 137(HFs 48-49)。

A7。 一位优雅的朝臣转身跟他身后的朝臣说话的动画,后者放低了双手。 Bonampak东厅1,北墙,西侧动画。 动画摘自并改编自Miller和Brittenham 2013:80,图。 142(HFs 75-76-77)。

正如Miller和Brittenham(2013:53)所述,房间1的舞者和音乐家后面的蓝色背景是闪闪发光的蓝色,它是由玛雅蓝色颜料的涂层和闪闪发光的青铜石层成的。 东墙的蓝色与深色的蓝色形成对比,深色的蓝色用作在3号房(和2号房)中绘制人物的背景。 通过在闪闪发光的矿物上覆盖颜色而获得的特定东部蓝色,是为了在白天暖色到来之前捕获黎明的明亮蓝光。 同样的蓝色也用作圣塔丽塔壁画东部黎明部分人物画的背景,并支持了卡维伊在东部黎明之神的角色中的表现(约翰2018:298,图5.1; F5)。 圣丽塔(Santa Rita)专门使用明亮和闪闪发光的蓝色来表示曙光,这表明颜色在概念上的使用具有悠久的历史,可追溯到后经典时代。 在圣丽塔(Santa Rita)以及邦纳帕克(Bonampak),随着黎明的进行,光线质量发生变化,分别在其东,南和西壁以及在其东,中和西室内反射。

F5。后经典的圣丽塔壁画重建。 The numbering (1-10) follows the general 'rhythm' of the two figure processions moving from the east and west towards the central door of the north wall编号(XNUMX-XNUMX)遵循从东和西朝北墙中央门移动的两个图形游行的一般“节奏”. 这些数字以东部闪闪发光的蓝色和西部闪闪发光的红色为后盾。

与其他壁画室相比,Bonampak 1号室的艺术家还使用较清晰的书法线条勾勒出人物的轮廓,并使用较厚的颜料填充其形状,从而使人物的形状更加明亮清晰(请参见Miller和Brittenham 2013:56)。 在每个房间中对人物的绘画处理上的差异,是为了表达黎明的光线,使之从黑暗的夜晚中再次充满东方的房间1和整个世界,呈现出明亮的新形状和新颜色。

Further evidence associating Room 1 symbolism with themes of beginnings is painted above the north wall actors performing the germination scene, where an important individual is shown three times to animate his robing.在进行发芽场景的北墙演员上方绘制了进一步的证据,将XNUMX号房间的象征意义与开始的主题相关联,在那里,三名重要人物被展示三次,以制作抢劫的动画。 Dressing was considered a symbolic敷料被认为是象征性的 开始 point in life, ritual and myth, representing a period when initial 'nakedness' was covered up (Miller and Brittenham 2013:127).生活,仪式和神话中的观点,代表了最初的“裸露”被掩盖的时期(Miller and Brittenham 9:XNUMX)。 The dressing scene is, therefore, easily comparable to the beginning of daily routines, the start of the day and the nudity accompanying birth.因此,穿衣现场很容易与日常的开始,一天的开始和出生时的裸体相媲美。 Placed immediately above the tier supporting the north wall actors, we are encouraged to also imagine the lord's dressing as a performance, his undressing comparable to the husking of the maize cob exchanged by the two deities below and his own person thus becoming the seed enabling future growth and rebirth.紧靠着支持北墙演员的阶层,我们被鼓励将幻想想象成主人的服装,他的脱衣服可媲美下面两个神灵交换的玉米芯剥皮,而他自己的人成为未来的种子生长和重生。 The two scenes are linked by a narrower tier containing attendants seeing to the lord's robbing needs and, in particular, by a green 'umbilical' cord [see FXNUMX] that is presented by a seated attendant to another holding up a large mirror that reflects the image of the cord up into the downcast vision line of the fully dressed lord.这两个场景之间由狭窄的层级联系在一起,其中包含服务员,以查看主的抢劫需求,尤其是通过绿色的“脐带” [参见FXNUMX],坐着的服务员将其呈现给另一个举起的大镜子,该镜子反映了绳索的图像一直到穿着整齐的主人的垂头丧气的视线中。

A8。 主修整的动画分为三个步骤。 Bonampak东厅1,北壁壁画细节。 Miller and Brittenham 2013:78,图。 133(HF 23-25-27)。

East Room壁画主题突出显示起点的另一个示例可以在几个球友的描绘中找到,他们被描述为等待比赛开始,而其他人则站在旁边等待表演(Miller and Brittenham 2013:121) 。 Amongst these figures, HF 71 has, furthermore, just在这些数字中,HF XNUMX仅具有 开始 从仍然完好无损的长度上可以明显看出来抽雪茄(参见Miller and Brittenham 2013:122,图232)。

A9。 球运动员在等待比赛开始时转动的动画。 Bonampak东厅1号,南墙和东墙壁画细节。 Miller和Brittenham 2013:80,图。 142(HF 65-66)。

此外, 婴儿 (HF 16)出现在贵族对面的南墙上, 萨哈尔 担任地区长官(Miller and Brittenham 2013:121-122),而在东墙上的信使则由他们的字形标题(例如: yebeet chak ha'ajaw,“他是红色或大水之王的使者”; Miller and Brittenham 2013:77,无花果。 130-131),以特定手势为他们的新消息传递动画; 他们示意宣布新信息的到来,从而带来新的开始。 的 萨哈尔 all wear spondylus shells suspended in 'three' about their necks.所有佩带的脊椎贝壳都悬挂在脖子上的“三个”中。 Shells were considered skeletal flowers of the dead and symbolised the nocturnal aspect of the sun;贝壳被认为是死者的骨骼花,象征着太阳的夜间活动。 the diurnal sun was symbolised by a blooming白天的太阳象征着盛开 亲属' 花(见约翰2019:234-241)。 的 sajals' 精心的安排揭示了隐藏的动画,这些动画使我们可以一窥古代的上流社会手势,它们的执行与它们戴在脖子上的三个贝壳有关。 最后,反映壁画的辐射布置进一步暗示了东方壁画室的诞生主题。 萨哈尔 就像它的两个中心人物(HF 8和9)的镜像一样,他们相互背对背,以吸引从两侧汇聚在他们身上的人物流。

A10。 Messenger手势的动画。 Bonampak东厅1,东墙壁画细节。 动画摘自Miller和Brittenham 2013:113,图。 212(HF 1-2-3)。

A11-12。 信使和上流社会手势的动画。 Bonampak东厅1,东墙壁画细节。 动画摘自Miller和Brittenham 2013:113,图。 212(HF 4-5和6-7 [从左到右])。

A13-14。 Bonampak东厅1号,南壁壁画细节。 2013(HF 113-212和10-11 [从左到右])。

F6。 Bonampak东厅1,南壁壁画细节。

A15。 Bonampak东厅1,下南墙壁画细节。 2013(HFs 113-212-67)。

西房间:

天涯和播种

3号会议室致力于牺牲和死亡(Miller和Brittenham,1:3),这被视为构成了使未来重生的扁圆的“种子”,也代表了秩序的恢复。 The preoccupation of Room 2013 with death and sacrifice is contrasted with the theme of agricultural renewal represented by以死亡和牺牲为中心的第143房间与以代表的农业更新主题形成对比 年轻 (绿色)玉米在东部的1号室壁画中。 Miller和Brittenham(2013:141)写道,第1室提出的对农业更新的预期被认为是第3室的牺牲和自我牺牲带来的,这两个房间是季节性并置的。

On entering the westerly room, ducking under Lintel 3 and looking up, we are reminded of the captive's death, speared by Yajaw Chan Muwaan's father [see A1].进入西风室时,躲在3号门下面并抬头仰望,我们想起了俘虏的死亡,这是由Yajaw Chan Muwaan的父亲所刺矛的[见A2013]。 A strong death theme continues into the interior of Room 34, which displays an opulent dance centred on a human sacrifice involving heart extraction (Miller and Brittenham 135:264, XNUMX, fig. XNUMX).一个强烈的死亡主题一直延续到XNUMX号房的内部,其中以围绕着提取心脏的人类牺牲为中心展示了华丽的舞蹈(Miller和Brittenham XNUMX:XNUMX,XNUMX,图XNUMX)。 Straight ahead, the culmination of the dance is given centre stage on the south wall, where two attendants swing a body they hold by its arms and legs high into the air to form an arch – possibly straight after the removal of his heart, indicated by an attendant holding a small serpent-headed knife and the heart in its encasing white pericardium kneeling on the steps immediately above.一直向前,舞蹈的高潮在南墙的中央舞台上出现,在那里,两名服务员将他们举起的胳膊和双腿高举的身体摆向空中,形成一个拱形-可能是在移开他的心之后直截了当地,表示为一位服务员拿着一把小蛇形刀,心脏在包裹着的白色心包中跪在上面的台阶上。

The blue tone of the sky painted behind the Room 3 figures standing atop the temple comes from a layering of blue pigment with both the minerals malachite and azurite, resulting in a darker sky than that used for Room 1 (Miller and Brittenham 2013:53).站在殿堂顶上的3号房间后面的天空的蓝色调来自一层蓝色颜料与矿物质孔雀石和青铜矿的叠加,导致比56号房间使用的天空更暗(Miller和Brittenham XNUMX:XNUMX) 。 In contrast to the other two mural rooms, artists have also executed Room XNUMX figures using thinner, more watered-down pigments and little black paint to outline their shape, which emphasises their colour and the heaviness of their human form (ibid:XNUMX).与其他两个壁画室不同,艺术家还使用更薄,更淡化的颜料和少量黑色涂料勾勒出他们的形状,从而突出了它们的颜色和人类形态的沉重(同上:XNUMX),从而执行了XNUMX号室的人物造型。 The visual effect matches the fading colours our sight experiences at the end of the day.视觉效果与一天结束时我们视觉体验的褪色相匹配。 The great care taken in employing different artistic techniques to create visual effects, including the use of colour, form and substance, shows the importance the Maya placed on distinguishing, not just via symbolism, but also stylistically, between scenes expressing dawn in the east and evening in west.采取各种艺术技巧来创造视觉效果(包括使用颜色,形式和物质)时,我们格外谨慎,这表明了玛雅人不仅要通过象征主义而且要通过风格在区分东方和西方黎明的场景之间进行区分,这一重要性很重要。西部的傍晚。

Further sacrifice is represented in Room 3 on its upper eastern wall by a group of royal ladies who let their own blood about a spiked bowl containing bark paper (see Miller and Brittenham 2013:141, fig. 279).一群皇室贵妇在其上东墙的XNUMX号房中表示了进一步的牺牲,他们让自己的鲜血围绕着盛满了树皮纸的尖刺碗(见Miller和Brittenham XNUMX:XNUMX,图XNUMX)。 The ladies sit on a large throne letting blood from their mouths.女士们坐在大宝座上,让他们的嘴里流血。 The mural scene composition surrounding the women expresses a circular motion accentuated by the green edges of their white女人周围的壁画场景表现出圆周运动,白色女人的绿色边缘突显出这种感觉。 huipil dresses and necklaces, which combine to resemble a rope binding the motion of their performance.礼服和项链,就像绑住表演运动的绳索一样。 The viewer's eye is initially drawn to the woman sitting on the floor before the throne, holding a small child in her lap.最初,观看者的眼睛吸引了坐在宝座前地板上的女人,她的膝盖上抱着一个小孩。 She faces away from an attendant kneeling opposite, who proffers bloodletting paraphernalia to the group.她背对着服务员跪着的膝盖,后者向小组提供放血用具。 The woman turns to look up at a young girl sitting on the edge of the throne, who bends to rest her head on the back of a portly woman seated directly in front of her, herself intimately engaged with a smaller female she faces, who twists away from the last woman shown immersed in pulling the rope through her lips.女人转身抬头看着坐在宝座边缘的年轻女孩,她弯腰将头靠在一个正坐在她面前的胖女人的背上,她自己与面对的一个较小的女性密密麻麻地订婚了,她弯腰远离显示的最后一个女人,她沉浸在通过嘴唇拉动绳索上。 All three women adopt the same hand gesture, binding their actions to the progression of time, further visualised by the three children seemingly growing from the infant held in the first lady's lap, to young girl, to adolescent receiving initiation into the bloodletting rite.这三名妇女都采用相同的手势,将他们的行动与时间的进程联系在一起,这三个孩子似乎从从第一夫人膝上抱起的婴儿,到年轻女孩,一直到放血仪式的青春期进一步显现。

The scene is similar to that of the enthroned lord shown seated high in the upper western wall section of Room 1, who, although not directly shown letting blood, sits on a throne beneath an oversized obsidian blade pointing down at him from the pincered jaws of an oversized deity head depicted in the vault above (see Miller and Brittenham 2013:125, fig. 235).场景类似于坐在XNUMX号房间西壁上段的位宝座的领主,虽然没有直接放血,但坐在宝座上,宝座位于一块巨大的黑曜石叶片下方,从其钳口下颚指向他。上方金库中描绘的超大神头(请参见Miller和Brittenham XNUMX:XNUMX,图XNUMX)。 The lord's implied blood sacrifice balances the presentation of the new child depicted on the south wall of the same room.主人隐含的献血与在同一个房间的南墙上描绘的新孩子的表现保持了平衡。 The lord sits surrounded by three women and an attendant standing to the left of the throne.主人坐在三位妇女的包围下,侍从站在宝座的左边。 Once again, a green 'rope' binds the scene to express temporal cyclicity leading to rebirth, flowing from the pictorial centre of the scene and the king's neck and jade earrings and bracelets down to describing the edge of the throne, the women's再一次,绿色的“绳子”将场景束缚起来,以表达导致重生的时间周期,从场景的画象中心以及国王的脖子和玉耳环和手镯一直流到描绘宝座边缘(女性的 惠皮尔斯 edges and the edge of theattendant's long skirt.边缘和话务员长裙的边缘。 As in the female blood-letting scene described in Room 3 (see above), the three women surrounding the lord in Room 1 appear of varying ages, possibly suggesting the lord's same female family members.就像在1号房中所述的女性放血场景中一样(见上文),围绕1号房主的三名妇女的年龄各不相同,这可能暗示了该主妇的女性家庭成员相同。 Indeed, some of their features, including hairstyles, match: the older woman sitting behind the lord in Room 1 partners the older woman seated on the throne at the far left;确实,它们的某些功能(包括发型)是匹配的:坐在3号房主的后面的老妇与伴侣坐在最左边宝座上; the younger female on the throne in front of the lord in Room XNUMX corresponds to the enthroned female sitting opposite (third from left);在XNUMX号房主面前的宝座上的年轻女性对应于坐在位的女性对面(左起第三位); while the youngest female seated on the floor by the throne in Room XNUMX shows similarities to the youngest child depicted pressing her forehead against the enthroned woman's back in Room XNUMX. Once again, the choice in representing而第XNUMX室坐在宝座旁的最小的年轻女性则与第XNUMX室中描绘的最小的孩子将前额靠在被神仙的女人的背部上有相似之处。 三 不同年龄的女性可以推断出时间驱动的衰老固有的生命周期。

1号和3号厅中的两个宝座场景都缺乏动画效果。 Their omission is likely due to the rituals performed by the lord and ladies being culturally well-known to the Maya viewers, immediately aware of the content of movements conducted.他们的遗漏很可能是由于领主和女士的仪式是玛雅观众在文化上众所周知的,他们立即意识到所进行的动作的内容。 The way they trigger knowledge of a conventionalised custom might be comparable to the modern representation of a traditional baptism, only requiring the presentation of an infant in a long dress beside a baptismal font to remind the modern viewer of the motions involved in the rite performed;他们触发常规习俗知识的方式可能与传统洗礼的现代表现不相上下,只要求在洗礼字体旁边穿着长裙摆出婴儿,以提醒现代观众观看仪式中涉及的动作; that is, the priest wetting the child's head with holy water.就是说,牧师用圣水把孩子的头弄湿了。

在整个东部房间壁画中都重复使用绿色“绳子”约束两个王座场景的表现,以指代时间驱动重生的周期性:例如,它也使呈现婴儿的人的长裙和腰带边缘出现在南墙上,并通过镜子隆重地呈现,由服务员在主人的着装和“怪异”的演员表演场景之间以及紧靠通向1号房间的北墙门上方的地方描绘(请参见F10)。

回到第3室,我们从死亡的象征中回想起舞者的后排架子上出现的骨骼cent,这是有毒和肉食性的助记符 蒺藜,在热带雨林中很常见,它们的觅食习性会加速分解,导致更新更快(Miller and Brittenham 2013:140-141)。 The depiction of dry (harvest) maize throughout the westerly murals also relates to sacrifice and offerings, the husks forming the seed for the在整个西风壁画中,干燥(收获)玉米的描述也与牺牲和奉献有关,果壳构成了种子的种子。 播种, 是下一季发芽和随后玉米生长所必需的(同上:141)。

The dance depicted in Room 3 is performed by ten individuals, elaborately dressed in high quetzal-feather headdresses that support supernatural heads and 'wings' extending either side of their belts.第2013会议室中描绘的舞蹈是由十个人表演的,这些人精心打扮成披着高个格调的羽毛头饰,支撑着超自然的头部和“翅膀”,延伸至皮带的两侧。 The dancers' elaborate quetzal feather headdresses would have cost the lives of many of these prized birds, who only produce two of these long tail feathers.舞者精心制作的格查尔羽毛头饰会使许多这种珍贵的鸟类丧命,而这些鸟类只生产其中的两条长尾羽。 The vast number of quetzal feathers serves as a metaphor for their great blood price.大量的格查尔羽毛代表了其高昂的血液价格。 They also speak of the vast wealth of the court (Miller and Brittenham 140:2013).他们还谈到了法院的巨大财富(Miller and Brittenham 142:XNUMX)。 The dance unfolds across the nine temple steps surrounding the victim.舞蹈在受害者周围的九个庙宇台阶上展开。 It is restrained, the dancers encumbered by the elaborate costumes they wear.这是克制的,舞者被他们穿着的精美服装所困扰。 Many of the dancers also hold axes, reminiscent of Chaahk's loud thunder, and fans, forming a mnemonic to wind.许多舞者还握着斧头,使人联想起Chaahk的雷声,还有粉丝,形成了助记符。 One dancer also wields a femur bone (Miller and Brittenham XNUMX:XNUMX).一位舞者还挥舞着股骨(Miller and Brittenham XNUMX:XNUMX)。

Chaahk被认为是雨与闪电之神(同上); however, he might better be seen as a god of rain and thunder, often shown wielding the deity K'awiil like an axe, who, in turn, embodies lightning (John 1992:17-2018).然而,他最好被视为雨与雷之神,经常表现得像斧头一样挥舞着神灵卡维伊(K'awiil),反过来又体现了闪电(约翰155:183-XNUMX)。 Creative acts and beginnings were possibly likened to lightning or the striking of fire, while thunder might have been equated with endings, metaphorically imagined as the sound of a flint axe splitting the sky.创造性的举动和开端可能被比喻为闪电或烈火,而雷声可能等同于结局,隐喻地被想象成a石斧劈开天空的声音。 Such thunder axes, akin to Thor's Norse Hammer or Damocles' sword, were considered inevitable and final.类似于雷神的《北欧之锤》或达摩克斯的剑,这种雷斧被认为是不可避免的,也是最终的。

A16。 皇家舞者的步骤的动画。 Bonampak West 3号房,西墙壁画细节。 动画摘自Miller和Brittenham 2013:129,图。 241(HFs 27-28)。

The winged loin cloth extensions of the dancers have been suggested as relating to auto-sacrificial bloodletting performed by their wearers, who also display sun attributes in their regalia (three of the dancers exhibit jaguar ears and pelts), all aimed at feeding the earth and Jaguar Sun of the Underworld, depicted high above in the north and south wall vaults (Miller and Brittenham 2013:136-141 and catalogue figs., pp. 216-225).舞者的有翼腰布延伸被认为与佩戴者进行的自动牺牲放血有关,佩戴者还在其服装中表现出阳光属性(其中三个舞者表现出美洲虎的耳朵和兽皮),目的都是为了喂养大地和《黑道的太阳》(Jaguar Sun),描绘在南北两面的穹顶上方(Miller and Brittenham 2013:141-1377和目录图,第9152-XNUMX页)。 The large sun heads in the vaults are mirrored across a red sky band to express the sun dyeing the sea red at sunset, evoking sacrifice.穹顶上巨大的太阳头映照在红色的天空带上,以表达太阳在日落时将海染成红色,引起牺牲。 Furthermore, two jawless deities are belched from large serpent maws emerging either side of the large Night Sun heads;此外,两个巨大的蛇爪ws出了两个无颌神Night,它们出现在大型夜阳头的两侧。 they are identified as the Patrons of Pax (Miller and Brittenham XNUMX:XNUMX), frequently also paired in ceramic scenes, where they receive sacrifices or hunt supernatural creatures (eg KXNUMX, KXNUMX).它们被确定为Pax的赞助人(Miller和Brittenham XNUMX:XNUMX),经常在陶瓷场景中配对,在那里他们接受牺牲或狩猎超自然生物(例如KXNUMX,KXNUMX)。

A17。 皇家舞者的步骤的动画。 Bonampak西3室,南壁上部壁画细节。 动画摘自Miller和Brittenham 2013:129,图。 241(HF 16和21)。

A18。 皇家舞者脚步的动画,看似像鸟一样下车。 Bonampak西3室,南墙下部壁画细节。 动画摘自Miller和Brittenham 2013:129,图。 241(HFs 26-25)。

“有翼的”舞者伴有两个乐队,一个由面部变形的人组成–建议戴上具有奥尔梅克特征的面具,以将壁画与时间联系起来(Miller and Brittenham 2013:142)–摇摇晃晃并敲打鼓,在西墙上方描绘,在舞者对面的北墙较低层代表一个,四个喇叭和一个拨浪鼓演奏者。 “矮人”乐队的音乐家人数众多,而且紧密地分组在一起,使他们的音乐更加强烈或仓促,响亮。 We can imagine the sound communicated by the mural imagery as music augmented by the stomping rhythm resounding from the dancers' feet.我们可以想象壁画图像所传达的声音,随着舞者脚上响起的踩踏节奏而增添音乐。 Small ovals attached to ankle and calf bands suggest possible bells tinkling with every step taken.附在脚踝和小腿带上的小椭圆形表明,每走一步,铃铛都会叮叮当当。 In addition, the long quetzal feathers of the dancers' headdresses and large 'wings' would have swished through the air, along with their fans, as they performed their cumbersome dance.此外,舞者的头饰和大型“翅膀”的格查尔长羽毛在舞动繁琐的过程中,也会与歌迷一起飞舞。

A19。 吹他的长角的音乐家的动画。 Bonampak西3室,北壁下部壁画细节。 动画摘自Miller和Brittenham 2013:136,图。 266(HFs 46-47-49)。

A20。 一对人物的动画在向前迈步时伸出警棍或五线谱,与另一对人物的动画相映成趣。 出现韵律时,动画形成了“排行榜”,排成一排的七个年轻人 ' 舞者在3号房间的东西墙之间的圣殿的较低台阶上进行表演。Bonampak West 3号房间分别是东墙和西墙的壁画细节。 动画摘自Miller和Brittenham 2013:129,图。 241(HF 11-12和HF 44-43)。

2号房间的噪音变化反映出白天即将结束,死亡和夜晚的寂静。 It seems as if sound is winding down, slowing its pace toward a more civilised order, fully re-established in easterly Room 3 and its preoccupation with rebirth.似乎声音渐渐减弱,朝着更加文明的秩序放慢了步伐,在东风1号房间完全重新建立,并重生。

As was the case in the most easterly room, in Room 3 a row of nobles stands watching the dance, this time from beneath the Jaguar Sun Head peering down on them from the north vault.与最东面的房间一样,在55号房间中,一排贵族站在观看舞蹈的地方,这次是从美洲虎太阳头下面从北穹顶向下凝视着他们。 Once again, their arrangement forms a visual chiasm reflected about two central figures, HFs 56 and 1. Either side, these figures' combined hand movements complete what probably form high-societal Maya gestures suited to the festive occasion.它们的排列再次形成了围绕两个中心人物HF XNUMX和XNUMX的视觉混乱。在任何一侧,这些人物的组合手势完成了可能形成适合节日场合的上流社会的Maya手势。 However, unlike in Room XNUMX, the two figures forming the central reflection of the chiasm face each other, moving towards each other, comparable to the sun entering the sea in the west, as opposed to the sun leaving the sea at dawn in the east.但是,与第XNUMX室不同,构成正畸中心反射的两个图形彼此面对,彼此相对移动,相当于太阳从西方进入大海,而不是太阳在东方黎明离开大海。

A21-22。 站立的政要们的动画在伴随动画演讲的手势中抬起和放下他们的手。 手势动画相对于 三 脊柱贝壳 三 “时间”石头,形成玛雅壁炉和创作的助记符。 Bonampak西3室,上北墙细节。 2013(HF 143-282和57-58 [从左至右])。

A23。 Animation of动画 Bonampak西3室,上北墙细节。 2013(HF 143-282-52)。

F7。 These Bonampak figures' hand gestures move about这些Bonampak人物的手势在移动 三 Bonampak West 3号房,北壁壁画细节。

中央房间:

生活是一场战斗的隐喻

最大 and most central of the three Bonampak rooms, Room 2, depicts an elaborate battle across three of its walls (east, south and west; Room 2 also boasts the tallest bench [higher by 10 cm; Miller 1998:241-242]).在Bonampak三个房间的最中央,房间XNUMX描绘了横跨其三个墙壁(东,南和西;房间XNUMX还拥有最高的长椅[高XNUMX厘米; Miller XNUMX:XNUMX-XNUMX])的精心战斗。 The mural symbolism expresses the Maya belief that for one ruler to thrive, another must die.壁画象征主义表达了玛雅人的信念,即一个统治者要壮成长,另一个必须死。 The room is overseen by Ux Yop Huun, the Maya Time God responsible for life's ascent, growth and fattening;这个房间由玛雅时代的上帝Ux Yop Huun负责,负责生命的上升,生长和发胖。 with the broad theme of the room communicating political ascent.会议室的主题广泛,传达了政治上的提升。

The sky above the battle scene on the south wall is a darker blue than that in the other rooms.南墙战斗场景上方的天空比其他房间的天空更暗。 The colour was achieved by the artists placing a thin layer of hematite red over a layer of Maya blue, creating a 'visceral sense of time and place' (Miller and Brittenham 2013:53).这些颜色是由艺术家将一层赤铁矿红色涂在玛雅蓝色之上,从而创造出一种“内在的时间和地点感”(Miller和Brittenham 2018:163)。 Indeed, the darker colour invokes thunderous clouds, and the hematite the red blood spilled in battle dyeing the atmosphere dark and ominous, while, simultaneously, feeding the earth and rain forest represented by a rich green backdrop behind the battling figures.的确,深色调唤起了雷鸣般的云朵,战斗中溅起的赤铁矿红血染成黑色和不祥的气氛,与此同时,为争斗人物身后的丰富绿色背景所代表的大地和雨林提供了营养。 The Maya frequently used red hematite to cover bodies and bones in burials (such as the Palenque Red Queen; see John 164:2014-2; Quintana et al. 2013);玛雅人经常使用红色赤铁矿覆盖墓葬中的身体和骨骼(例如帕伦克红皇后(Palenque Red Queen);参见约翰46:XNUMX-XNUMX;金塔纳等人XNUMX); its inclusion in the mural pallet thus fittingly highlights themes surrounding spilled blood and death.它包含在壁画托盘中,因此恰好突出了围绕溢血和死亡的主题。 In addition, Room XNUMX is the only mural room that revealed a subfloor crypt (Miller and Brittenham XNUMX:XNUMX), the hematite layer thus forming an elaborate funerary canopy covering the body.此外,第XNUMX室是唯一一个露出地下隐窝的壁画室(Miller和Brittenham XNUMX:XNUMX),赤铁矿层因此形成了覆盖人体的精致fun仪顶篷。

The chaotically arranged battle scene contrasts with the ordered presentation of figure rows placed in neat tiers on its north wall (Miller and Brittenham 2013:105), a regularity which also represents the usual presentation of figures in mural Rooms 1 and 3. The three battle-scene walls of Room 2 feel alive, sprung with movement bursting out of their very edges.混乱的战斗场景与在北壁整齐排列的人物行的有序呈现形成对比(Miller and Brittenham 2013:101),这种规律性也代表壁画房间102和XNUMX中人物的通常表现。 -房间XNUMX的场景墙活灵活现,运动从其边缘突然爆发。 The chaos of the hand-to-hand combat conveys simultaneity and disorder, which Miller and Brittenham (XNUMX:XNUMX-XNUMX) imagine as the least scripted and shortest part of Maya warfare – in contrast to regularised rituals marking the beginning and end of battles, such as music, banners and the eventual binding and stripping of captives.肉搏战的混乱传达了同时性和混乱性,米勒和布里顿纳姆(Miller and Brittenham,XNUMX:XNUMX-XNUMX)认为这是玛雅战争中最少的文字和最短的部分–与标志着战斗开始和结束的常规仪式相反,例如音乐,横幅以及最终的绑架和剥夺俘虏的行为。 Writhing figures within the battle imagery convey the brutality and noise of war: battle cries seemingly swirl about the room like the driving gale of a hurricane.战斗影像中的扭曲人物传达了战争的残酷和喧闹:战斗的哭声似乎像飓风的狂风般在房间里旋转。 Many more figures are packed into the battle scene than appear in any other of the Bonampak murals.与其他Bonampak壁画相比,进入战斗场景的人数更多。 The increased head count suggests a loss of order, with figures overlapping, even blending together, ever-swelling towards a frenzied climax.人数的增加暗示着秩序的丧失,人物重叠,甚至融合在一起,不断涌向疯狂的高潮。 The feverish motion pivots wildly around a point at the centre of the south wall:发烧的动作绕着南墙中心的一个点疯狂地旋转:

尽管总体效果是混乱的,但是这种混乱是经过精心计划的:战士们拿着长矛,并且在战斗的任何给定部分中,长矛似乎都是朝着随机的方向瞄准的,但是尽管如此,它们还是会聚在中心右侧。最低级别,好像将注意力集中在HF 51和52上

(Miller and Brittenham 2013:21)。

The animations we have detected add urgency to the battle movements and their sound and further draw attention to important moments taking place within the mêlée.我们检测到的动画增加了战斗动作和声音的紧迫性,并进一步引起人们关注大剧院内发生的重要时刻。 For example, a musician, or possibly a military trumpeter, spills across the south-east corner in a great arc to sound his trumpet.例如,一个音乐家,或者可能是一个军号手,以极大的弧度溢出东南角,以吹响他的号角。 The long instrument is painted with crossed bones and eyeballs, while disembodied heads swing from about the trumpet player's neck [A24].长长的乐器涂有交叉的骨头和眼球,而无形的头部则从小号演奏者的脖子上摆动[A25]。 Diagonally opposite, in the lower south-west corner, a warrior is shown collapsing to the floor and into the very centre ground of the south wall mural mentioned above [AXNUMX].斜对面,在西南下角,一个战士被折叠倒在地板上,并塌陷到上述南壁画的正中央[AXNUMX]。

A24。 吹奏乐器的小号手的动画; 他的动作描绘了一条弧线,穿过2号房间的东西壁壁的角落,就像太阳在天空中升起然后下降一样(HF 7和35)。

A25。 战士以逐渐脱衣服的状态倒在地上的动画,以突出他的失败。 Bonampak中央厅2,南墙壁画细节(HFs 64-58-52a)。

Above the battle fray, a hieroglyphic caption records the lord Yajaw Chan Muwaan capturing a warrior;在战斗边缘上方,有一个象形文字的字幕,记录了Yajaw Chan Muwaan阁下俘虏的一名勇士; the text represents the longest and widest caption found in all three mural rooms (Miller and Brittenham 2013:68, 75), fitting with the overall 'fat' theme exhibited by Room 2. The ruler-warrior is shown grasping an opponent he has overwhelmed by the hair, his power mirrored in his jaguar headdress swelling in size to reflect his increased might and political stature [A26].文字代表在所有三个壁画房间中找到的最长和最宽的字幕(Miller和Brittenham XNUMX:XNUMX,XNUMX),与房间XNUMX展示的整体“胖”主题相吻合。标尺-战士显示抓住了他不堪重负的对手从头发上看,他的力量反映在美洲虎头饰的大小上,以反映出他威武和政治地位的提高[AXNUMX]。 The artist has left an unusual amount of space around the ruler within the swirling mass of battling figures to allow the animation to play out and further draw attention to Yajaw Chan Muwaan's performance.艺术家在战斗人物的漩涡中留下了不寻常的空间,以使动画得以播放并进一步引起Yajaw Chan Muwaan表演的注意。

F8。 Yajaw Chan Muwaan的前进过程显示,他的长发抓住了被推翻的俘虏。 Bonampak西2室,南墙细节。

A26。 Bonampak Central Room 2,南壁壁画细节。 2013(HF 94-172)。

The battle scene is presented off centre;战斗场景不在中心。 as you view the south wall mural the focus is off to the lower right and represents the 'key and peak moment visually' (Miller and Brittenham 2013:85, 98).当您查看南壁壁画时,焦点会移到右下角,并在视觉上代表“关键时刻和高峰时刻”(Miller and Brittenham XNUMX:XNUMX,XNUMX)。 The imbalance lends a dynamism to the scene which we believe was done intentionally in emulation of the anatomy and placement of the human heart within our bodies, which is also asymmetrical.这种不平衡给场景带来了动感,我们认为这是在模仿人体心脏在人体中的解剖结构和放置的过程中有意进行的,这也是不对称的。 The slightly skewed layout of the scene forms a simile to the beating heart – which sits off centre in the left of the thorax – of the battle, or, that of the deity depicted in the vault above, thus rendering the mural rooms comparable to the body of a god.场景的稍微偏斜的布局形成了搏动之心的比喻,它位于战斗的中心,位于胸部左侧的中心,或者位于上方金库中的神灵,因此使壁画室与神的身体。 The body consists of身体由 三 parts: the head of the god is placed in the vault, the torso in the middle, where hand gestures dominate, and the legs in the lower registers, which show walking, dancing or the motion of battle.零件:神的头放在穹顶中,躯干在中间,手势占主导地位,腿在下半部,显示走路,跳舞或战斗动作。 Ever-pulsating, ever-turning around the beating 'heart', the battle scene does not represent a single snapshot of the occasion, but rather expresses the constantly oscillating fight between defeat and victory – to reflect any and every battle, including that of life and death.不断跳动,不断旋转的跳动的“心脏”,战斗场面并不能代表一时的景象,而是表达了失败与胜利之间不断摇摆的斗争-反映了包括生命在内的任何一场战斗和死亡。

The measured hand gestures of the ten dignitaries depicted on the upper south and north walls of Room 1 and 3, respectively, frame and contrast with the frenzied hand movements of the warriors depicted in the battle scene of Room 2;在XNUMX号和XNUMX号厅的南北壁上分别描绘了十位贵宾的手势,并与XNUMX号厅的战斗场景中描绘的勇士的疯狂动作形成了鲜明的对比。 the ten十 萨哈尔, organised in two pairs of five, become comparable with the number of fingers found on a human's hand, symbolic of counting and, by extension, time.分为两对,每对五个,可以与人的手的手指数量相媲美,这象征着计数以及时间的延伸。 Dismembered fingers have been found in Maya offerings (Chase and Chase 1998:308-309; Miller and Brittenham 2013:112), as are teeth, which change over the life span of a human;在Maya产品中发现了肢解的手指(Chase和Chase XNUMX:XNUMX-XNUMX; Miller和Brittenham XNUMX:XNUMX),以及在人类生命周期中变化的牙齿。 both fingers and teeth were likely linked to time.手指和牙齿都可能与时间有关。

Linear visual order seemingly returns to the central room on its north wall, comparable to a return to court from the field of battle, or the K'iche' farmer returning home from the heat of the day.线性视觉秩序看似回到了北壁的中央房间,相当于从战场上回到了法庭,或者是K'iche'的农民在白天热度中返回家园。 The king stands – like the sun risen high into the sky – atop the temple at the centre of his court and amongst displays of war spoils, 'fattening' gained from the battle depicted on the remaining three walls.国王站在法院中央的圣殿顶上,就像太阳升入天空一样,在战利品的展示中,从剩下的三堵墙上描绘的战斗中获得了“脂肪”。 The figures' arrangement appears more spaced and choreographed to suit the sombre occasion;人物的摆放看起来更加间隔和精心编排,以适应严峻的场合。 they do not walk, but stand to occasion, like a regimental guard.他们不走路,但像军团警卫一样站立。 Subtle animations build suspense as figures wait on the king's instructions.随着人物等待国王的指示,微妙的动画产生了悬念。 For example, to the king's left, figures 95-96 exhibit a slight shift in the position of their left-hand fingers;例如,在国王的左边,图92-93的左手手指位置略有偏移; to his right, figures 27-121 frame the motion of a torch or sceptre they lower [A122], while, above and below, figures 28-115 [A116], 29-111 [A112] and 89-90 change the positional grasp of hands on their spears, repeated also by figures 30-XNUMX [AXNUMX], to the king's right.在他的右边,图XNUMX-XNUMX描绘了他们降低的割炬或权杖的运动[AXNUMX],而图XNUMX-XNUMX [AXNUMX],XNUMX-XNUMX [AXNUMX]和XNUMX-XNUMX上方和下方改变了位置抓地力国王的右手同样以矛矛作图,也被图XNUMX-XNUMX [AXNUMX]重复。 The subtle movements hint at the anticipation, or 'nervous' fidgeting of the courtiers awaiting the king's inevitable decision, petitioned by a captive cowering at his feet supplicating for mercy.这种微妙的动作暗示着等待国王的必然决定的朝臣们的期待或“烦躁”烦躁,被俘虏的cow缩在他脚下cow缩恳求怜悯。

A27。 Bonampak Central Room 2,北壁壁画细节。 2013(HF 75-125)。

A28-30。 贵宾们的动画改变了他们的手握住矛的位置。 中央动画还表达了人物头饰尺寸的膨胀。 Bonampak Central Room 2,北壁壁画细节。 动画摘自Miller and Brittenham 2013:75,103,图。 125、190(HF 89-90、115-116和121-122 [从左到右])。

The north wall displays a swirl of sacrificial victims taken in the battle presented to Yajaw Chan Muwaan (Miller and Brittenham 2013:94-95).北墙展示了献给Yajaw Chan Muwaan的战斗中牺牲的牺牲者的漩涡(Miller和Brittenham XNUMX:XNUMX-XNUMX)。 The entire scene is topped with a wide band displaying star glyphs that, in combination with the imagery below, expresses a variation on the Mayan glyph整个场景的顶部都有一个宽幅显示的星型字形,结合下面的图像,表达了玛雅字形的变化 朱比 or 'is thrown down', consisting of a Venus star symbol placed above the conquered site – most likely intended to refer to Yajaw Chan Muwaan overwhelming his enemies (ibid:105);或“被扔下”,由被征服地点上方的金星符号组成–最有可能是指Yajaw Chan Muwaan压倒了他的敌人(同上:XNUMX); the star cartouche at the far right displays a turtle whose shell is marked with the最右边的星状漩涡装饰显示了一只乌龟,其外壳上标有 三 “时间之石”。 The enemy captives are displayed below the star band spirally ascending temple stairs stretching across three horizontal tiers.敌人的俘虏被显示在星带下方,螺旋形上升的神殿楼梯横跨三个水平层。 The lord stands centrally at the temple summit surrounded by royalty, also shown watching from the temple base below, while the middle rung, stretching immediately above the entrance to the room, consists of three steps supporting nine captives depicted in profile [F9].领主站在神殿的顶峰中央,神殿被皇室包围着,从下面的神殿底部也可以看到,中间的梯级正好延伸到房间入口的上方,由三个台阶组成,支撑着九只俘虏,轮廓[FXNUMX]。

F9。 1。

Traditionally, the Bonampak captive scene has been viewed as a depiction of nine separate figures.传统上,邦纳帕克(Bonampak)的俘虏场景被视为对九个独立人物的描绘。 However, we here suggest that it probably represents the animated sequence of one single individual shown approaching his own sacrifice in 'nine' steps;但是,我们在这里建议,它可能代表了一个人的动画序列,显示了他以“九”步接近自己的牺牲; a number, incidentally, which refers to the nine chthonic levels of their world, forming the victim's imminent destination.顺带一提,这个数字指的是他们世界的九个震级,构成了受害者的迫在眉睫的目的地。 What becomes important is to read what lies between, the unseen and overarching concept expressed by the figures depicted in this elaborate visual pun acting much like the merismi frequently used in Maya literature.重要的是阅读介于这间精致的双关语中的人物所表达的,看不见的,总体的概念之间的含义,这种行为就像玛雅文学中经常使用的梅里斯米一样。

要阅读场景并拍摄动画,观看者的眼睛必须沿着壁画壁移动。 直到现在,才有可能追随俘虏的故事,通过他的人在壁画中所处的2013个姿势来讲述,而且这些姿势在构图上分为三个部分,以通过“三个”来表达动画动作。 艺术家通过在故事中的三个重要时刻暂时“停止”叙事流程来建立悬念。 Miller和Brittenham(112:XNUMX)以现代人认为电影的方式描述了北墙上的图像排列。 时间向内盘旋,沿顺时针方向移动,直到到达中心并到达死点为止。

The story begins its rotation by animating the captives' triadic representation 'awaiting' torture to the right of the slain body [F9a].这个故事开始旋转时,将俘虏的三合一表示动画化为“等待”被杀者尸体的右边[F9a]。 It then moves to the left of the wall, where an attendant removes his captive's fingernails;然后它移到墙的左侧,服务员在这里移开俘虏的指甲。 pain is clearly captured in the facial grimace and tension of the right palm pressed rigidly against the floor [F9b].面部鬼脸明显感觉到疼痛,右手掌紧紧地压在地板上[F31b]。 Next, the cycle turns upwards and to the viewer's right, where a figure triad seated a step above animates a head-rocking motion conveying anguish [FXNUMXc and AXNUMX].接下来,脚踏车向上转动并向观看者的右边转动,坐在三脚架上方的人物三脚架为传送摇晃的痛苦的摇头动作动画[FXNUMXc和AXNUMX]。 Within this group the first representation of the captive throws his head back to the level of the horizontal step supporting the dignitaries above, oblivious to his suffering.在这个小组中,俘虏的第一个表示将他的头转回到支撑上述政要的水平台阶的位置,而忽略了他的痛苦。 The movement is continued by the victim's second depiction, tilting his head back down to stare straight ahead, the horror frozen on his face, while his third representation, eyes downcast and wide with terror, observes his bleeding hands.受害者的第二次描绘继续了这一动作,他的头向后倾斜以直视前方,恐惧被冻结在他的脸上,而他的第三次描绘则低垂而恐怖地睁着眼睛,观察着他流血的手。 All the while the victim progressively lifts his hands up from his lap, blood animated to drip from his wounded fingertips.受害人一直在逐步将手从膝上抬起,鲜血从受伤的指尖流下。

A31。 钉子被移走后,被俘虏的手指在痛苦中摇摆着的血液动画,这是一种折磨。Bonampak Central Room 2,北墙壁画细节。 从Miller和Brittenham 2013:103中提取和改编的线条图动画,图。 190(HF 102-103-104)。

Once again, the momentum halts, this time stopping at the temple summit, where the captive unsuccessfully petitions Yajaw Chan Muwaan for mercy [F9e].势头又一次停止了,这一次停在了圣殿山顶上,在那儿,俘虏未成功地向Yajaw Chan Muwaan求情[FXNUMXe]。 Sacrificial victims, considered spoils of war, were thus seen as a 'currency' 'fattening' Yajaw Chan Muwaan's victorious cause.因此,被视为战利品的牺牲受害者被视为“货币”“胖化” Yajaw Chan Muwaan的胜利事业。 Expansion, or growth in tribute, is conceptually shown by the prisoners' ascent of the three temple stairs, akin to the upward thrust demonstrated by flourishing plants or growing children.囚犯在三个庙阶上的上升从概念上显示了扩张或致敬的增长,这与茂盛的植物或成长中的孩子所表现出的向上推力相似。 Consequently, it appears that the ancient Maya symbolically equated political 'fattening' with victory, control and conquest.因此,看来古老的玛雅人象征性地将政治“陷于僵局”等同于胜利,控制和征服。

Finally, captive position nine highlights the inevitable moment of his preordained death;最后,俘虏位置九突出显示了他预定死亡的必然时刻。 he is shown slumped across the steps, larger than life, at the ruler's feet [F9e].如图所示,他俯伏在台阶上,比尺子还长寿[F2018e]。 In addition, the mural stresses that the victim's sacrifice forms a vital component in the circle of life by arranging his representations in a broad loop centred about the corpse of him slain.此外,壁画强调,受害人的牺牲是通过将被害人的尸体以被杀者的尸体为中心的大范围排列来构成生活圈中的重要组成部分。 The circular arrangement creates the impression of the motion of continuous spinning or turning, such as is required of the viewer to absorb the murals in the Bonampak rooms as they pivot about their own axis.圆形的布置给人以连续旋转或转弯运动的印象,这是观看者在Bonampak房间中围绕自己的轴旋转时吸收壁画所需要的。 Moreover, the limp right leg of the victim's body rests on a decapitated head, paradoxically placed in the upright-angled birth position associated with K'awiil (see John 176:XNUMX) and atop fresh green grass, thus expressing the death event leading to opposed, yet consubstantial, cyclical rebirth.此外,受害人身体的the行右腿靠在断头的头部上,这与K'awiil相关联(见约翰XNUMX:XNUMX),并在新鲜的绿草上呈直角分娩姿势,因此表现出导致死亡的事件反对但实质性的周期性重生。

Ux Yop Huun从上方的空中穹顶监督中央房间的政治景象。 他从战斗的混乱中重新建立秩序,反映出昼夜,死亡与生命之间的永恒斗争。 壁画象征意味生活中的机会,就像战斗的随机性一样。 就像在这个房间中记录的“日历回合日期”(每隔52年重复一次)一样,战斗本来会随着时间而重复,但每次战斗都是相同而又不同的。 因此,房间2的总体目的可能是表达将生命比喻为战斗的玛雅比喻:为了生存,必须死亡。 房间2,生命房间,与血统保持平衡。 Bonampak国王的崛起与对手的俘虏和灭亡是平衡的,类似于小号手在吹奏乐器时的上升和下降,就像天空中太阳的上升和下降一样。 观众走进房间时,经过尚未被俘虏的俘虏(头顶刻入门into 2号),他们发现自己紧贴在死去的壁画战士下方,无意间被表演吸引了(Miller和Brittenham 2013:105)。 壁画的全部目的也许是为了提醒我们自己的死亡。 生存的奋斗是我们所有人努力成长和成功所面临的挑战,就像树木在坚不可摧的森林中争夺光明; 然而,无论我们如何战斗,我们注定要失败,正如时间周期和生命周期所规定的那样。

结论