About the Project

Below we present our theory on how to read Maya art and how this has led on to new insights into Maya religion and philosophy.

Studying the animations hidden in ancient Maya artworks has led us to propose that these ancient people worshipped a trinity of gods (Chaahk [responsible for Death]), Ux Yop Huun [Growth and Life] and K’awiil [the God of Birth); they are comparable to the Hindu Trimurti (Shiva [the Destroyer], Vishnu [the Preserver] and Brajma [the Creator]), creating a conceptual link between Asia and the Americas.

The Unseen in Maya Art

In Maya thought time was a union, where the seen was bound by the unseen.

Consequently, in order to more fully understand Maya artworks and books (codices), we need to project the unseen onto them. Playing the ancient animation below, for example, we need to look at what is in-between a pair of figures painted on either side of a ceramic.

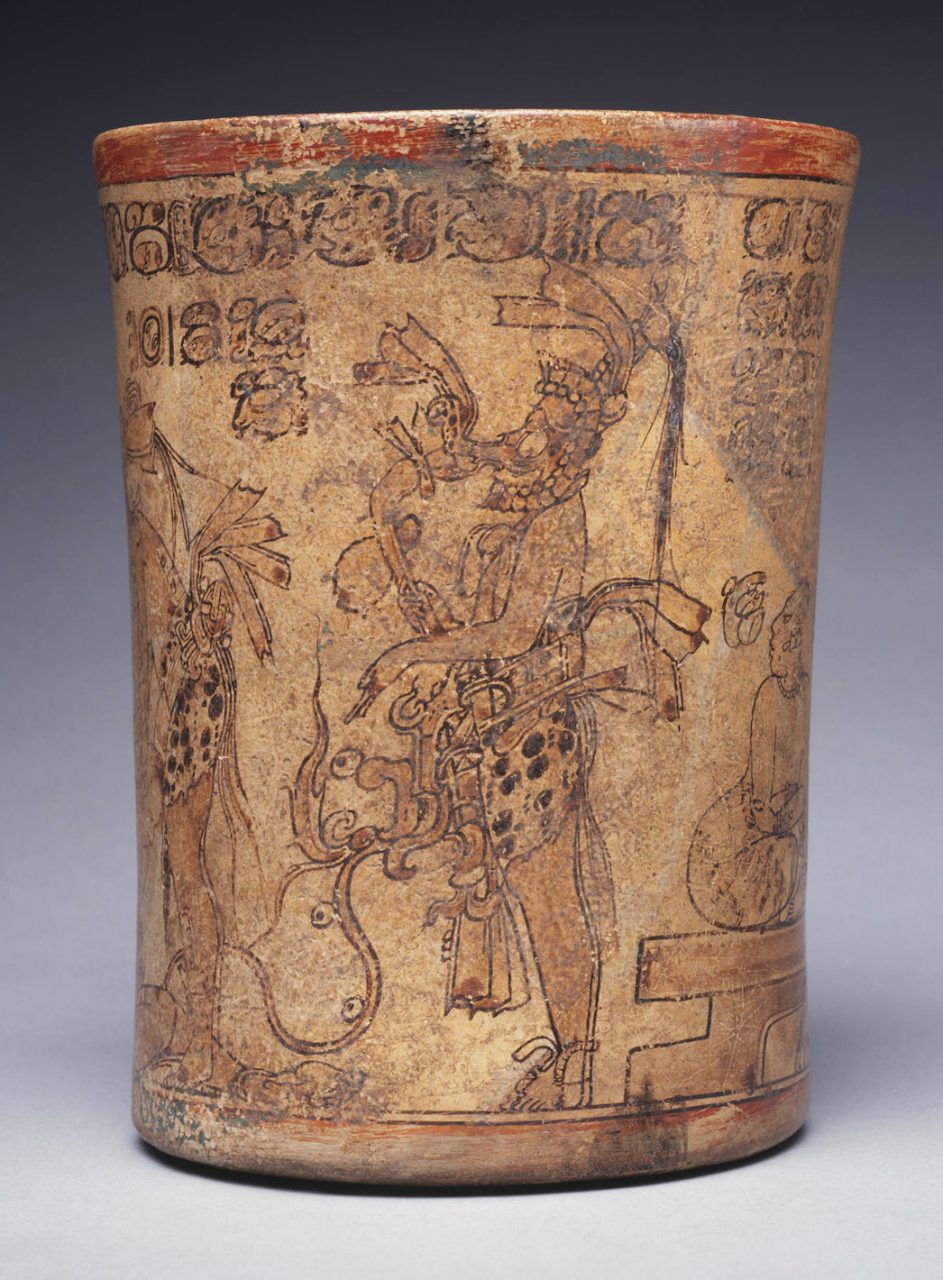

Animation extracted and adapted from vessel no. 1978.412.202. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Purchase, Nelson A. Rockefeller Gift, 1967.

Circular ceramics would have been held and turned by the ancient Maya; this process is frequently difficult to appreciate when the priceless artefacts are displayed in glass cases in modern museums, where parts of the ceramics remain obscured to the viewer. Here, photogrammetry based models of the artworks have a role to play.

Princeton Vase 1. Maya ceramics were intended by their creators to be turned in the viewer’s hands; the motion unlocks their image sequence and animates the figures displayed. This Late Classic example (see 3D model above and extracted animation below) animates a seated figure to lean forward in conversation while raising his hand.

Late Classic Maya Cylinder vessel depicting a seated noblemen on each side, A.D. 600-800. Ceramic with polychrome slip, h. 12.3 cm., diam. 10cm. (4 13/16 x 3 15/16 in.); gift of Gillet G. Griffin; y1969-101. Courtesy of Princeton University Art Museum.

Turning the 3D ceramic model makes clear how the space-time between the two seated figures creates an animation, as presented above in the seated lord raising his arms. Key is to see what is different between the figures and to ‘see’ the unseen, the in-between. Consequently, to advance our understanding of Maya ceramic art we have to move away from using the rollout photographic methods that have been so popular in the field in the last few decades; instead, we need to return to examining the 3D object, the ceramic, itself by using 3D models like the one above kindly prepared by Jeffrey Evans (Princeton University Art Museum). Students will then be able to appreciate the extra temporal dimension first hand.

This hidden ‘unseen’ dimension forms the visual equivalent to the phonetic and literary devices that the Maya used when composing written works like the Popul Wuj. These literary constructs allowed Maya poets to incorporate the ‘unseen’ into their works. One such device, a merismus, communicates a broad central concept by joining elements that express a narrower meaning. For example, ‘sky-earth’ represents creation as a whole, or ‘deer-birds’ refers to all wild animals in the Popol Wuj (Christenson 2007:48). The two words either side frame the ‘unseen’ concept which the reader has to imagine, and fill-in.

We recently detected a new merismus in the Popol Wuj: ‘Thunder-bolt’, where the ‘in between’ connected by the two words ‘thunder’ and ‘bolt’ encourages the reader to imagine the ‘count’ that results after seeing a lightning bolt strike and hearing its delayed rumble of thunder, the clap. In this way, ‘thunder-bolt’ forms a poetic reference to what separates and yet binds the concepts expressed by the two words; that is, the broader notion of time separating the lightning flash from the thunder. This same merismus, referring to historical time, is recorded as having been used by the Aztec Emperor Moctezuma during a conversation with Cortés.

‘It is true that I [Moctezuma] am a great king, and have inherited the riches of my ancestors, but the lies and non-sense you have heard of us are not true. You must take them as a joke, as I take the story of your thunders and lightnings [read times or histories]’

(Díaz del Castillo 1963:224, authors’ parentheses).

J_Yaxchilan 1. Details of Yaxchilan Lintels 13 and 14, from Structure 20, that animate the Lady Chak Chami tilting a bowl towards her brother, the sajal Chak Chami; the two lintels represent the visual equivalent of a merismus: two separate images connected by what is in the middle and unseen, that is the ‘third’ concept of movement and unseen, cyclical time.

Another literary device used by the Maya to structure their writing is called a chiasm. Concepts expressed are inversely reflected across a central component, in that events are described and then redescribed in reverse order. Consequently, the prose brings two halves together via an unseen centre, often referring to water and its properties of imperfect reflection. The text is therefore imperfectly reflected across its murky centre. For example, the Popul Wuj section below reflects the text lines imperfectly about the central line (‘Come from across sea’).

Because there is not now

(in Christenson 2007:14).

Means of seeing of Popul Vuh

Means of seeing clearly

Come from across sea,

Its account our obscurity,

Means of seeing light life, as it is said.

There is original book anciently written also,

Merely hidden his face

The unknown Maya poet used this literary device to draw the reader’s attention to what is unseen between the complementary lines. The verse centres on a reference to the sea and, indirectly, its reflective surface at dawn in the east. It represents a poetic frame to describe the state of the primordial sea during creation.

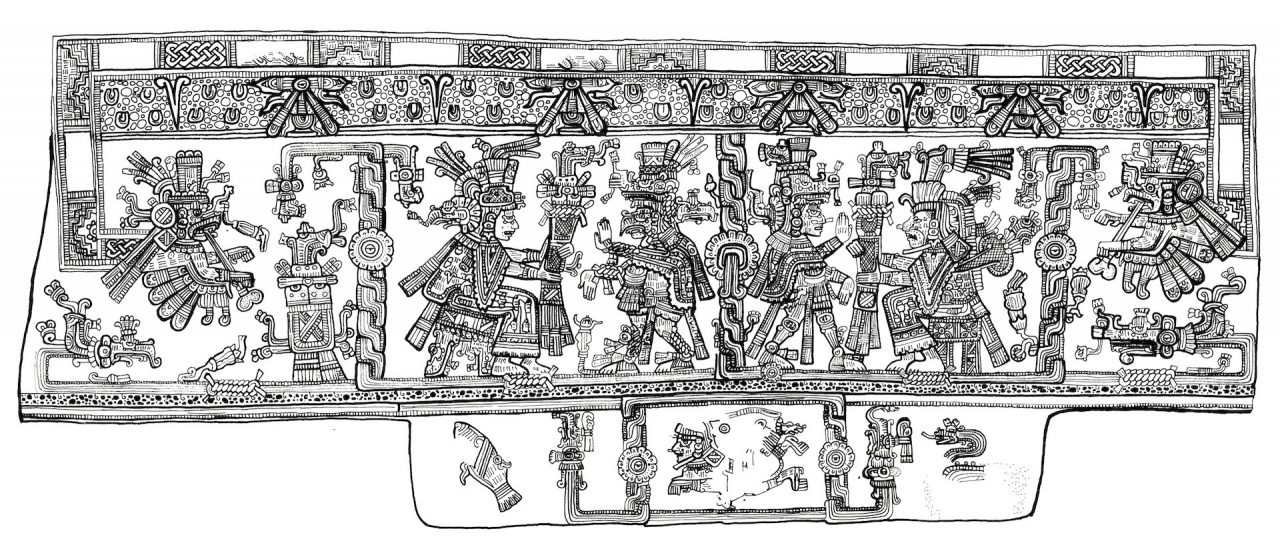

[1] Late Postclassic Tulum Structure 5, interior east wall, Mural 1. The entire scene is ‘reflected’ with imperfect symmetry, like a mirror, referring to creation and new beginnings overseen by K’awiil (the God of Birth). After Miller 1982: plate 28.

We believe that the ancient Maya saw the act of creation taking place at the centre of two imperfect halves forming a larger whole. Acts of genesis – beginnings – happen all around us, involving different parts being brought together to create something new, such as soil, water, sun and seed in combination producing maize. In the same manner, man and woman (two imperfect halves) join to bear life, and water, earth and fire are all necessary in making ceramics.

Making art was balanced by its destruction and its cyclical renewal; creation was offset by endings. Ceramics were made, then smashed and buried, such as at Lamanai in the Postclassic. In the reading of Lamanai funerary ceramics it became necessary to understand that the ritual ‘death’ of the ceramic completed its artistic performance.

J_Naranjo 2. Inverted details of a Classic period Maya vase revealing the inter-becoming the Maya saw in all things; in this instance, the flower becomes then bird and vice versa, they are one. As the vase is turned in the viewer’s hands, triadic bird-flower fusions are animated to ‘fly up’ and across the surface of the vase; similar bird-flowers occur on polychrome vessels also elsewhere. Animation extracted and adapted from Reents-Budet 1994:159, fig. 4.50.

The philosophy we touch upon is one of inter-becoming. The Maya understood how time connects us and therefore, rather than seeing the force of time simply as the agent of decay, the Maya celebrated time as the enabler of action, inter-becoming and oneness; because without time, there would be no being or self. Consequently, the Maya worshipped the transformative power of time, allowing all things to be formed – that is come into being to live – before unravelling according to the perpetual, unseen order of transformation.

This becoming is all around us. It occurs within a growing tree, the gathering of a wood bundle, the burning of a fire and the carrying of a fire. It is present in the making of a ceramic, the breaking of a ceramic, the weaving of cloth and rope and their undoing and wear. It is present in the feeding of an animal, or a jaguar eating, and thus becoming, a deer. And it is found in a flower opening and closing with the rhythm of the day. Our life’s performance is similarly connected to time and the world.

The source of inter-becoming lay in the driving force of the Gods of Time, whose performance Maya artists strove to imitate, recycling in their art this philosophy on life in metaphors reused in constantly changing ways, each occasion different and yet the same.

This unseen subtext is fundamental to understanding Maya artistic performances. Visual equivalents to the literary devices described above (merismus and chiasms) are incorporated into Maya artworks to reveal hidden depth. Our work reveals that Maya artists, sculptors, scribes and architects deliberately incorporated the ‘unseen’ into their creations. Consequently, seeing the unseen activates ancient Maya animations and expresses what lay at the core of their ancient philosophy; with the motion by which art works were viewed forming the key to their animation. Like Einstein, the Maya understood that space and time were related, an insight they utilised to create ‘moving pictures’ (see Maya Gods of Time).

[2] Classic period Maya architecture displaying chiasmic visual structuring centred around its entrance; the ‘Arch’ at Labna , Yucatan, Mexico. See also Copan Str. 2, displayed in the Museo de la Escultura Maya, Copan.

Chiasmic structuring in Maya mural programmes has been previously uncovered at Bonampak (see Miller and Brittenham 2013:68). We have also detected its use in the long mural sequence from Santa Rita (in Northern Belize) and at Tulum (Structue 5, East wall [3]), and in paired (lip-to-lip) ceramics. All these artistic compositions form a visual juxtaposition (like the literary devices described above) relating to the interaction of the sun with the reflective sea; this dualistic thinking allowed two different, yet complementary, halves to come together to ‘create’ a greater whole.

J_Palenque 2. Classic period Throne Tablet, west side, from Palenque Temple XIX, displaying the eighth century ruler Ahkal Mo’ Nahb III and an individual named Sajal-B’olon (‘Nine-Military Lord’) conducting a political ceremony in AD 731. Between the figure on the left and the right (the unseen), we can detect motion; his head tilts back, his right hand drops from his shoulder and his left palm moves down to press upon his knee. Simultaneously, his Ux Yop Huun headdress grows and he lifts the spotted, soft handle of a rectangular pouch or basket trimmed with feather tassels with his right hand up to his left shoulder. Displayed in the Museo de Sitio de Palenque, Alberto Ruz Lhuillier.

The animated details highlight the movement of an attendant performing a gesture of reverence towards Ahkal Mo’ Nahb III.

All cultures choose to embed their philosophy in their art. As soon as an artist is aware that he or she is ‘making art’, they are unable to separate their conscious or subconscious cultural circumstances from their creations. For example, Islamic art incorporates deliberate errors into its artworks, as their makers believed that only Allah could make perfect works; and Australian Aboriginal art deeply connects with a philosophy centred upon their land and ancestry. To the Maya, the unseen in their artworks related to a philosophy based on time. Time was perceived as an unseen force that connected what was visible in the world.

Our work reveals that the Maya also used other unseen elements, such as wind and sound, as metaphors to express the concept of time. Architecture incorporated the ‘unseen’ by defining air through giant stone ‘Ik’ (wind) symbols, defining vacant spaces within them, such as rooms and courtyards, and also the space between them. The spaces simultaneously connected to the unseen by acting as sonic spaces; the Maya used stones like acoustic shields to create whispering phenomena, echoes and amplify sound within these spaces. Like time, sound was also unseen, with time’s count likened to the beat and rhythm of sound.

The concepts touched upon elevate Maya art and architecture, revealing a previously undetected dimension of philosophical vitality. Travelling across Mesoamerica, this new perspective – the rediscovery of an ancient philosophical outlook – will transform visitors’ experience and understanding of this ancient culture.

While our book, The Maya Gods of Time, explores the ‘unseen’ idea behind ancient Maya animations, this website aims to showcase the moving animations we have discovered in a way our static book could not; and in this way act as a platform for future discussions and explorations.

Time as Three

This brings us to the questions:

Why did the ancient Maya build their temples, and group their artworks, in three? Why was the old Mexican flag decorated with three stars? In effect, what was the symbolic significance of ‘three’?

We know that three-stone places were sacred to the Mesoamerican people, who frequently built their cities at the centre of ‘three’ mountains and in groups of ‘three’. The repetitive way in which ancient Mesoamerican towns were planned relates to the great ritual importance they attached to this triadic structure. It explains, for example, why Santiago Atitlan was chosen to be located in the shadows of the three Guatemalan volcanoes San Pedro, Atitlan and Toiliman.

Likewise, Mexico City (covering the location of the ancient Aztec city of Tenochtitlan) is built at the centre of a great mountain range, whose three highest peaks were likely symbolically significant. Teotihuacan was also built at the centre of three great mountains, with the city itself replicating these mountains at its centre with its three largest temples, and also within its smaller three-temple complexes, whose alignment connected to the calendar counts and therefore time (Headrick 2007:104).

We know that the Maya also organised other cities according to this structure (e.g. Chichen Itza) and even grouped towns in threes, such as Naranjo, Yaxha and Nakum, or Tintal, Wakna and Nakbe. Christenson (2001:76, 2007:67) notes how in mountainous areas nature provided these elevated ‘stones’, whereas in flatter areas, like the Maya Lowlands, they had to be built as three-turreted structures, or three great stone temples.

Previous research has linked these architectural ‘stones’ to the three hearth stones and the stones of creation (e.g. Milbrath 1999:266-268; Rice 2007:147; Taube 1998:434-443; Tedlock 1996:236). We believe that we have solved the ancient Mesoamerican mystery surrounding the number three; and that all triadic arrangements presented refer to three-part time. As a result, we propose that the three stones set in place during creation relate to the three-part structure ordering time and that concepts of time are tied to the sacred Mesoamerican three-stoned hearth, ballgame and even profane daily uses, such as grinding maize with a mano et metate and weaving on a loom.

Beyond the grouping of structures, sites and stones, this thought drove us to question why the Mesoamerican people chose to support their ceramics with three feet? Why they repeatedly painted three figures on ceramic exteriors? And why stone artworks (stelae, panels and lintels) frequently display visual sequences grouped in three?

[2] Princeton 3D Vase 2. When turned in the viewer’s hands, Maya ceramics reveal their animation. Above, a seated figure is animated, in ‘three’, to raise his hand in an instructive gesture (see also Animated Themes / Hand Gestures).

Late Classic Cylinder vase, A.D. 600-800; reddish brown ceramic, buff slip exterior, decoration in brown slip-paint exterior burnished except for centre of base; h. 15.2 cm., diam. 20.4 cm. (6 x 8 1/16 in.); gift of Leonard H. Bernheim Jr., Class of 1959; y1979-65. Courtesy of Princeton University Art Museum.

The Duality of Time

We found a clue to why the Maya structured their artwork in three in their association between stone and time, evident in the contemporary use of the ancient word of pre-Proto-Mayan origin, tuun, translating both as ‘stone’ and ‘year’ (of the 360 days in the Maya Long Count calendar), which we suggest may be read as ‘time’. The link of stone with time also occurs in the inclusion of the word tun in terms used to define specific time periods, for example, a k’atun, baktun, piktun, kalabtun or kinchiltun (Stuart 1996, 2010:289).

It turns out that the dualistic meaning of the word tuun refers to the oppositional structure the Maya saw embedded in time. Understanding this forms a key to approaching Maya cultural works structured in three.

The Maya perceived time as being ‘heavy’ and possessing a weight or mass comparable to stone, evident in hieroglyphic texts, which show individuals crippled under the burden of ‘time’ they carry on their backs (see Pharo 2014:119-126). This heavy mass of stone and time was counterbalanced by its unseen motion, which was likened to wind and sound. As previously mentioned, stone temples were balanced by unseen space and unseen sound.

Our suggestion is that stone represents more than simply time per se; rather, it was associated through its mass with the elliptical movement of time, and that the three stones of time were perceived as providing structural support for this cyclical motion. The association of a solid and permanent substance such as stone with an entity as fleeting and intangible as time ties in with the deep-held Central American tradition of dualistic thinking; clearly both distinct from, and advanced in relation to, European thinking of the time.

Expanding upon this duality, we find the tangible (known) defined by the intangible (unknown); certainty balanced by chance; the seen (stone time) defined by the unseen (motional time); and stability being opposed by complementary change.

Stability and ‘Three’

The Maya conceived the three-part foundation of time stabilising the ‘moment’ (the now) and also the ‘perpetual’ (infinite) transformative power of time. Accordingly, the Maya believed that cyclical change provided stability to their world and that a central point was offset by spinning motion. This means that ancient Maya meditations on time balanced ephemeral constructs with art and architecture built to endure.

Think about how we ‘stand atop’ time, how each of our moments, our experiences, rest on top of time. All our choices and actions that connect to the present are framed either side by the past and the future, thus, in effect, resting upon three-part time. The Maya recognised this three-part structure as governing time and, long ago, took its philosophy to underpin their life’s journey and artistic works.

J_Bonampak 1. Details of Classic period Bonampak Lintels 1 to 3, carved and painted on their underside and supporting the three doorways leading into Structure 1 shown in the image above (left to right). To absorb the sum of the artwork the viewer must walk between the three lintels. Pieced together, the sequence animates the spearing of a captive grasped by his hair.

It is possible, indeed probable, that the idea behind the Maya philosophy of ‘three’ linked to time, support and stability arose from a simple yet powerful observation, comparable in importance to the story of Newton, who, through questioning as to why an apple drops to the ground from a tree, led to the theory of gravity. Newton’s physical laws relate force to motion, and subsequently birthed the deterministic philosophy that would dominate scientific thinking for centuries to come. It is possible that the Maya similarly observed that three stones placed around a fire was the number required to securely support a cooking pot. But the real answer to this is lost and we must accept that we will probably never know how these concepts became entrenched in the Mesoamerican numerical system, the calendar, the ballgame, food preparation, artworks and books.

Notably, the three feet of ceramics connects them to the three stones placed around fires. Engineering laws prescribe a minimum of three ‘feet’, constructed in a triangular form, to stabilise a platform; for example, a stool with two supports only becomes stable through the addition of a third leg.

The concept of ‘three’ conferring stability from below is mirrored by objects suspended by something above. An object hanging in space by a single support, like a weight attached to a thread spun on a cotton whorl, dangles and is unstable – it spins and turns. When an object is hung by two strings it becomes more stable; it can still move, but only in one plane. It is only when three strings are attached to an object that it achieves true stability in space. Using three points to stabilise objects has many practical applications: at Kingston harbour on Norfolk Island, boats and other large objects are lifted and lowered to the surface of the sea via three points of fixation. Symbolic evidence that the Maya also recognised this phenomenon may be found in the carved stone lintels they frequently suspended above their structure doorways in triptychs; the motion of a weaving shuttle passing through its frame supported by the latter’s three supports; and the action of ball games having been played out about three stone markers placed in ball courts.

In relation to Maya temples and artworks, the viewer needs to accept that their alignment and imagery were connected to time by the ‘unseen’. Immediately, previously static temple and art groupings, connected by paths of ‘unseen’ human motion, spring to life. Walking the Avenue of the Dead links the three famous temples at Teotihuacan; circular walking joins the three temples of the Palenque Temple of the Cross Group; while at Dzibilchaltun and Chichen Itza, sacbe (ancient walking paths) connect structures grouped in three. Similarly, walking between the three towns of the Ixil triangle in the Guatemala Highlands connects their group to three-part time. Elsewhere in the Americas, ancient Inca mountain trails connected shrines visited at prescribed ritual dates to Machu Picchu, where walking celebrated the motion seen in the cyclical progression of time.

Question: What is to be said

When a man is seen on the road?Answer: Time

(Maya riddle; in Edmonson 1986:50, 121)

Similarly, the massive translated to the minute and mundane. A woman’s circular movements, grinding maize with a mano on a metate, was stabilised by its three stone feet. The motion of a shuttle passing through the weaving loom was supported by the three parts of its frame. Similarly, the motion of carrying stones to build and renew temples related to the duality present in time.

Maya Number System and ‘Three’

It has long been understood that the Maya were great mathematicians, famously using the concept of zero long before Arabian mathematicians did so, and closely following the cyclical motion of planets, the moon and stars. Unsurprisingly, the Maya developed a great love for numerology (when numbers or counts are merged with concepts), the numbers themselves, at some point, having acquired mystical properties.

This love is evident in the association of the Maya number three (ox) with time becoming integral to the construction of their entire numerical system; and, moreover, the composition of their structure of time. Ox is represented as a numeral by three dots or stones.

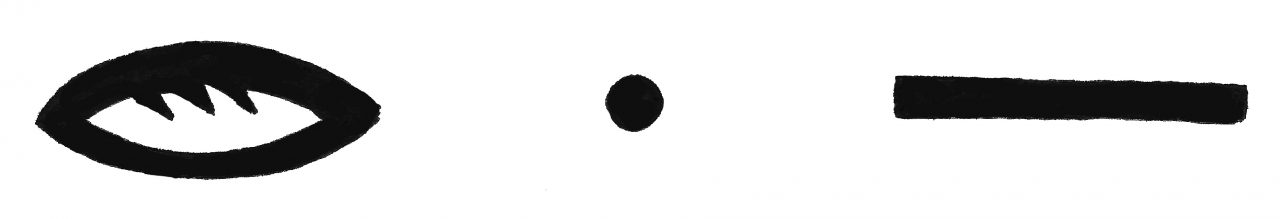

Smaller numbers (excluding those for larger periods) were entirely composed from three symbols (numerals): the cross-section of a shell (zero), a solid horizontal bar (five) and a dot (one), which were combined to build all numbers.

The way the Maya built numbers from three parts reflected the way in which they saw time to be built in three parts. The Maya numerical system is very old, as early examples of this system are also found among the Olmec and Zapotec cultures.

[3] Three dots in the Maya numerical system designate the number three, ox or ux.

[4] The three symbols making up the basic Maya numerical system: 0, 1 and 5 (left to right). Maya numbers are built from these three symbols.

Incorporated into Maya epigraphy, the three dots of the number ‘three’ form the supports of Maya day-sign cartouches (ahaw), the most elementary unit by which time was counted.

Three (time) was therefore seen to support the day.

Maya Calendar System and ‘Three’

The ‘day’ glyph ahaw is supported in a similar way that the three feet of tripod ceramics support their bowls and dishes displaying animations. Other Maya time units exhibiting three visual supports that mimic the number ‘three’ include the central (interchangeable) patron of the month glyph of the Classic Maya calendar, the Long Count Initial Series Introducing Glyph (ISIG). The ISIG marks the beginning of recorded time periods and may therefore be associated with the beginning of time units and time.

The visual form of the number ‘three’ both resembles and embodies the three sacred stones, which are repeatedly described as having been central to Maya creation accounts. We believe that the three stones of creation are in fact a representation of three-part time. Moreover, the creation of three-part time representing the pivotal moment of creation. Before the creation of time, there existed a static limbo in which past, present and future had no order. Time and space were not yet organised.

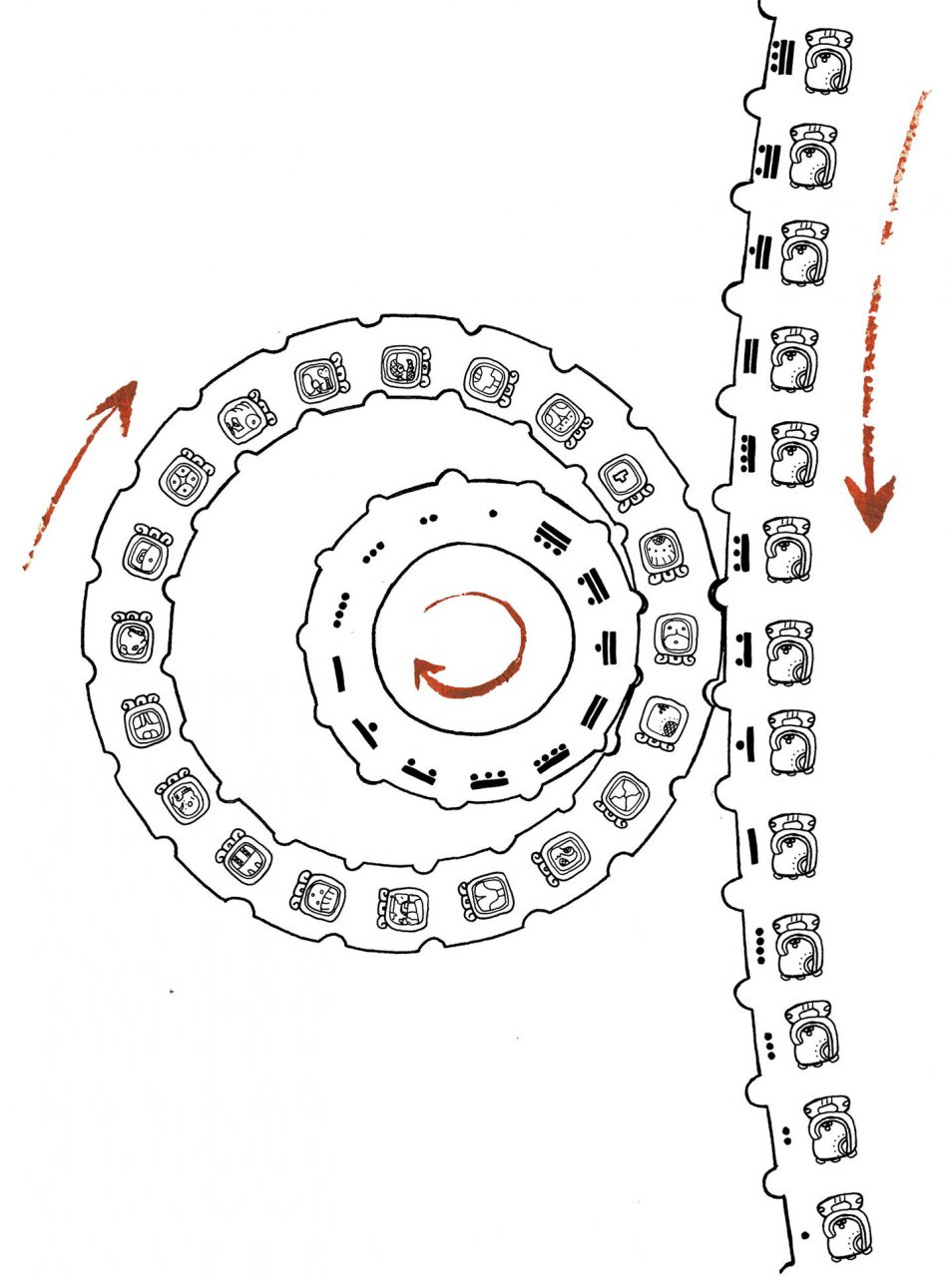

While other counts existed, the ancient Maya mainly relied on three calendar forms to track time; two were cyclical, the ritual Tzolk’in and the agricultural Haab, which contrasted with a linear Long Count, comparable to our Georgian Count. The Maya Long Count marked the count of time since the Maya creation date of 4 Ahaw 8 Kumk’u.

In addition, the two cyclical calendar systems, the Tzolk’in and Haab, came together, interlocking to chart the turning of time using three imaginary wheels. The main 260-day Tzolk’in calendar was composed of two wheels – a 13-day numbers cog placed within the larger 20-day names wheel – which ensured the timing of ceremonies cyclically repeated each 260-day ‘year’. Conversely, the 365-day Haab round consisted of 18 months, containing the complete agricultural cycle and forming an approximation of the solar year. Together these calendars conceptually created a 52-year calendar.

Three (time) was therefore seen to support the count of time (the calendars).

The Maya also marked the passage of the solar year in relation to the horizon in ‘three’; for example, structures at Uaxactun, Caracol and Calakmul were positioned to mark the three equinox points.

Three (time) therefore was seen to support the passage of the sun with the solar year.

The Metaphor of the Day, Historical Reoccurrence and ‘Three’

The examples mentioned all connect with the Maya metaphor linking people’s lives to the ‘day’. In Highland Guatemala, K’iche’ men walking from their home to the field and back again, returning to the cool of the house at noon, were tied to a three-part motional rhythm (Earle 2000:80-81); the men’s agricultural chores, furthermore, changed throughout the year to match the seasons, in that they corresponded with, or were joined to, the changing motion of the sun in its relation to the horizon.

| Dawn | Field | Noon | Field | Dusk |

| House | Motion | House | Motion | House |

The same ‘solar’ journey – connecting people to the rhythm of the day – may be found in the act of walking between triptych temples, lintels and on entering the ‘houses’ perched atop temples grouped in threes, for example, when ascending and descending the Palenque Cross Group Temples (see Archaeological Sites / Palenque, Bonampak). The motion of walking between the temples becomes balanced by a stationary moment within the house.

This sacred Maya duality – movement juxtaposed with momentary inertia – also connected to the mundane, such as the daily routine of men walking to the milpa to tend their crops, or women processing corn to make tortillas. All actions formed complementary halves of a whole that was bound together by the rhythm of time.

Similarly, the duality of time connected three-stone complexes to the motion of the ballgame. While each game had the same beginning, its performance and outcome would never be identical. Like the day, each game was similar and yet always somewhat different.

With this insight, we can surely suggest that the ancient Maya recognised the concept of historical reoccurrence (e.g. see Archaeological Sites / Palenque and Bonampak).

As Mark Twain is famously reputed to have said: ‘History never repeats, but it often rhymes.’ Interestingly, sound resounds like history itself. It is possible that the Maya perceived time as a repeating echo. So, while there is a broad structure to life, in Central America this ‘frame’ was paradoxically balanced by the idea of uniqueness; no two types of love are the same, no two ballgames are played in exactly the same way, no two trees in a forest grow identically, and no two fires are ever set up to burn in the same way.

J_Yaxchilan 2. Yaxchilan Lintel 53 and 54 details animating subtle movement between a lord with a K’awiil sceptre and royal female holding a tied bundle. Even though the royals displayed might represent different individuals, their involvement in near-identical ceremonies highlight the Maya notion of historical reoccurrence, played out by the elite over time in repeated rituals. Animation extracted and adapted from Graham 1979: plates on pp. 27-30.

The Gods of Time

In our book, The Maya Gods of Time, we lay out detailed evidence showing how each of the three stones of creation was tethered to a different god, which were in turn related to an aspect of cyclical time.

To understand how the ancient Maya perceived time as having ‘parts’, placed within a turning cycle, it is helpful to look at the work of the great Mayanist Tatiana Proskouriakoff, who in 1960 published her landmark paper ‘Historical Implications of a Pattern of Dates at Piedras Negras’. Her research showed the frequent repetition of the three ‘life event’ verbs she translated as ‘birth’, ‘accession’ and ‘death’.

These three major event verbs prompted us to consider that the Maya perceived cyclical time as being structured. The triadic pattern is repeated throughout Maya epigraphy and art. In fact, it was the frequent repetition and cyclical recurrence of these three verbs, carved into the stone faces of Piedras Negras stelae, that enabled Tatiana Proskouriakoff to decipher their meaning.

We propose that the three gods relate to cyclical time and that their ‘three-part’ cycle of change formed a stabilising structure that was placed within a dualistic framework. Furthermore, we suggest that these three gods mimicked how the structure of time perpetually forms and deforms all things; each deity was assigned a particular role within the process of cyclical decay and renewal, which we believe to include a God of Creative Destruction bringing death, a God of Birth ensuring renewed dawn, and a God of Life sustaining growth.

Consequently, a sacred trinity was worshipped in Mesoamerica long before the Christian arrival of God the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost, which possibly explains the merging of iconographic and spiritual elements in artworks and structures built by indigenous labourers.

For example, churches, frequently constructed using stone recycled from indigenous temples, were built with three towers incorporated into their façades, thus mimicking ancient three-stone complexes. The indigenous labourers were possibly integrating clandestine Maya symbolism, hoping to keep their supressed religion alive, such as ‘three’ and the ‘cross’ (similar to their World Tree); we hope to study this in greater detail in the future.

Whatever the nature of the symbolic assimilation, over time, the Gods of Time slowly became transformed, to merge with the Christian Trinity of Gods, until they were wholly forgotten. The ancient Maya Gods of Life, Birth, and Death became God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost.

Evidence supporting this deity trinity permeates Maya symbolism, pre-conquest Maya codices, Postclassic Maya books and appears in sixteenth century Spanish accounts reporting on their early contact with the indigenous population in Central America.

Our breakthrough and new perspective came from studying the animations that we present in this website.

Time God Trinity in the Popul Wuj

The Postclassic Maya trinity of Time Gods is repeatedly named in the Popul Wuj:

First, Thunderbolt Huracan (as death, seen as a type of sowing),

Second, Youngest Thunderbolt (as birth),

Third, Sudden Thunderbolt (as the moment of life and growth).

In Maya Gods of Time, we show how the Popul Wuj text always refers to these three Thunderbolt deities within a broader theme related to cyclical time. Their title, ‘Thunder-bolt’, forms a merismus, a literary device, that highlights what binds the two words ‘thunder’ and lightning’; that is ‘time’, to refer to their shared roles. We also explain in Maya Gods of Time how the three Thunderbolt deities are related to their Classic predecessors Chaahk, K’awiil and Ux Yop Huun (more commonly known as the Jester God).

Even though separated into three individual entities, the different roles or forces of the three Classic period Time Gods ultimately interlink in a hermeneutic cycle describing the circle of life and time. The three gods look very similar, evidence of their relation; moreover, their close inter-being is symbolically expressed by their tight iconographic associations. As such, the Time Gods are frequently represented as three near-identical stone heads with long and upturned noses covering temple façades, where they occupy prominent positions.

God of Life (God the Father): UX Yop Huun (‘Three Time?’)

The God of Life or Growth was linked to the biggest, most central Maya temples, such as the Temple of the Sun at Teotihuacan, the Castillo at Chichen Itza, the Temple of the Cross at Palenque, or the largest, central Bonampak mural room. The largeness relates to this deity’s role as the God of Life and Growth, as the ‘Provider’ and ‘Sustainer’ (as he is described in the Popol Vuh), he was tied to life’s moment and the instant in which we live and grow.

Maya animations show this deity being ‘lifted’ up, usually in relation to rulers ascending to the throne, that is ‘growing’ in their role to take on new responsibilities (see Time God Ux Yop Huun in Animated Themes and J_Palenque 3 and J_Bonampak 6 in the Archaeological Sites sections). The process of lifting (or ascending) relates to the concept of vertical growth, via time.

Linda Schele daubed this deity the ‘Jester God’ due to three protruding elements ending in baubles projecting from his hat, which resembles that worn by Medieval Court Jesters. On closer inspection, the projections are animated to lift and grow in size; for example, on the Vase of the Seven Gods, in the Yaxchilan Lintels 1-3 Triptych (see Maya Gods of Time, figs. on frontispiece, i and ii) and on Lamanai Stela 9 (see ibid: fig. 3.20).

Notably, the biggest and ‘fattest’ jade (stone) ever found in the Maya world, excavated by Dr. David Pendergast at Altun Ha, was carved as an effigy of this deity.

The God of Growth was tied to the three-stone hearth burning at the centre of every Maya household, where he ensured provision and growth. It has been noted that a similar deity symbolically existed at Teotihuacan and in the Olmec region, known as the Fat God, who has also been linked to the three-stone complex through his association with the hearth as the food preparatory locale of a house, with his image, moreover, often found decorating stones.

The God of Growth was worn by royalty like a crown attached to a paper headband. The deity’s position on the very top of the ruler’s head further supports his association with upward growth. This deity has previously been described as a symbol of kingship and royalty, associated with accession to the throne (Freidel 1990; Miller and Martin 2004:68, Schele and Miller 1986:53); that is, ‘stepping up’ or ‘growing towards’ lordly responsibility.

[10] Late Classic Ux Yop Huun headband diadem from Aguateca, Peten. Displayed in the Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología, Guatemala City.

In our book, we present detailed literary evidence further tying this deity to themes relating to growth. The first part of his name, Ux/Ox, moreover, clearly binds the deity of growth, Ux Yop Huun, to ‘three’ and time, the force driving ‘fattening’ during life. While Räxa, in the first part of his Postclassic Thunderbolt name, as recorded in the Popol Wuj, translates as ‘Sudden’, a moment of time, and the consciousness placed at the centre of Maya three-part time; this explains why the deity is usually worn as a headband-crown at the centre of royal foreheads, to signal their royal consciousness aiding the process overseen by Ux Yop Huun, of driving growth and life.

In summary, this deity relates to the process by which a child grows, a town is built, or a city expands. He is the god of political development and fattening and the force behind the growth of a tree and the growth of maize. As such, he controls the way our life develops. Walking up the steps of a soaring-high temple, we mimic this deity and the sun rising in the sky, to celebrate our lives ascending towards their prime. The God of Growth represents the ‘moment’ of life in which we live, ascending in growth and cradled either side by birth and death.

God of Beginnings and Birth (God the Son): K’awiil

The God of Birth is tied to eastern temples and the direction of the rising dawn sun; he is the god of new beginnings and creation and represents the ancient Maya insight that everything possesses a beginning. An echo of this concept might be found in modern ‘birthstones’, still relating birth to the concept of stone across the world.

Stones are associated with the birth of creation in Maya accounts (e.g., Popol Wuj) and are specifically referred to as being three times ‘born’ in the Book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel (Roys 2008 [1933]:63, 65), which ties the three stones to the three Time Gods.

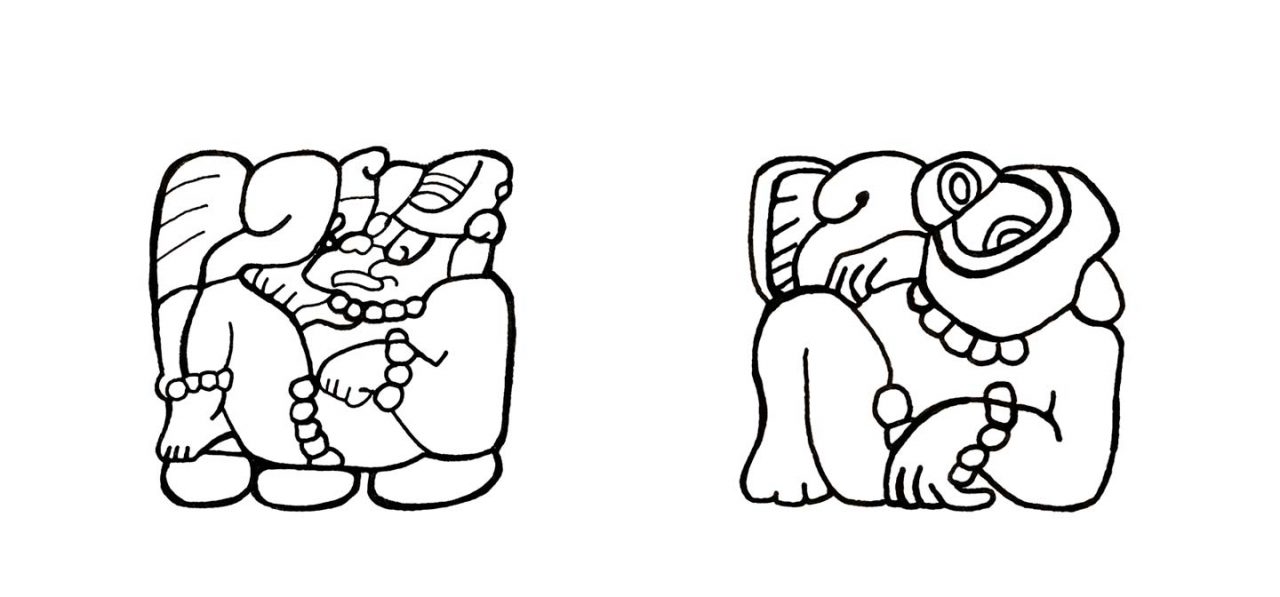

The Time God related to birth was bound to the Classic period deity K’awiil and his later Postclassic equivalent Youngest Thunderbolt, whose description as the ‘youngest’ forms a clear reference to birth. As the youngest of the three Time Gods, this deity is frequently depicted as a new born child; for example, in the figurative form of his name glyph and at Quirigua, where he is carried like an infant on the shoulder of a lord [13].

[12] K’awiil is carried like a child on the shoulder of the ruler depicted on Quirigua Stela H, south face.

K’awiil is associated with serpents in birthing scenes and is repeatedly shown tilting his head up and back in a ‘headfirst’ position, imitating the way a baby crowns when being born and the Mayan ‘birth’ glyph sihi; thus strengthening his association with birth and new beginnings.

The God of Birth is frequently positioned in the relative east and is therefore associated with the dawn of the sun. For example, K’awiil is painted on the ceiling of the most easterly mural room at Bonampak, and he appears in a mural painted on the eastern wall of Tulum Structure 5, perched on a cliff edge overlooking the eastern sea (see Tulum [Mexico] in Archaeology section); his ceramic effigy was placed at the eastern side of a Postclassic Lamanai burial (see Lamanai [Belize] in Archaeology section); and the eastern Palenque Cross Group Temple, the Temple of the Foliated Cross, was dedicated to this deity (Milbrath 1999:xx). K’awiil is thought to be the Maya equivalent of the Mexican God Quetzalcoatl, who reportedly came from the east, bound to the temple of that name at Teotihuacan.

As well as being bound to the east, our work reveals that K’awiil was also symbolically tied to reflection. His forehead is frequently marked with what has been suggested to form a mirror sign conveying brightness (Schele and Miller 1983:9, 1986:43); the sign has more recently been suggested to read lem, meaning ‘to shine’, ‘flash’ and also possibly signifying ‘lightning bolt’ (Stuart 2010:291-292).

In the Santa Rita murals K’awiil stands at the centre of a reflected animation juxtaposing the rising of the dawn sun with the setting of Venus. K’awiil also appears on a wall within the most eastern Bonampak mural room receiving a maize cob from the Wind God, thus he is shown being given the seed necessary for future germination and birth.

God of Creative Destruction (Holy Ghost): Chaahk

J_Chaahk 1. On rotation of this Classic period Maya vase, Chaahk is animated to swing an axe down onto the neck of a victim, who crouches at his feet, stripped of all his regalia and with his arms tied behind his back. Animation extracted and adapted from vessel no 32221. Courtesy of Princeton University Art Museum; museum purchase, gift of the Hans A. Widenmann, Class of 1918, and Dorothy Widenmann Foundation.

The God of Creative Destruction is associated with western temples and stones, descent, falling rain and death; as such he forms the opposite of Ux Yop Huun and the latter’s association with ascent and growth. The God of Creative Destruction’s Classic period equivalent is Chaahk, who dominates the upper vault of the western Bonampak mural room, he is tied to the symbolism displayed on the walls of the great western Ballcourt at Chichen Itza and celebrates the end of day in the western Temple of the Sun in the Palenque Cross Group.

The deity’s destructive role initially encourages an association with endings, such as gravestones and the setting sun. However, of all the Time Gods, he is the one who most clearly embodies the theme of dualistic time. He is tied to descent and decline leading to death yet is balanced by the hope of future rebirth. He is associated with sacrificial blood, but also the deliverance of water (Taube 1992:18-23). It seems that Chaahk embodied sacrifice and the creative ‘seed’ without which birth or growth would be impossible, and which embodies the philosophy that for something to live something must die. His name in the Popol Wuj, Thunderbolt Huracan, is still retained in our modern word hurricane, bringing vast destruction in a storm. He is the god of crumbling rust and destructive hail, he is ‘death’ that forces balancing ‘dawn’ and creation.

Until now, Chaahk has been predominantly considered a rain god (see Taube 1992; Stone and Zender 2011:40-41); however, we suggest in Maya Gods of Time that while this deity does relate to rain delivering growth in return for offerings, the central concept associated with him actually revolves around the notion of ‘something returned for something given’.

Our reconsideration of this deity’s central concept, however, is not wholly new, but fits with Eric Thompson’s earlier analysis of Chaahk:

The Chacs sent rain [see also Thompson 1990 [1950]:251],

(Thompson 1990 [1950]:10-11, authors’ brackets).

but they also sent hail and long periods of damp,

which produced rust on the ears of corn.

The Chac might therefore be shown as

a beneficial deity or as a death dealing power.

In the latter case he could be presented with a

skull replacing his head,

and with other insignia of death

Accordingly, while Chaahk is responsible for general acts of sacrifice and death, he is also linked to the ‘creation of newness’; ‘the strike of Chaahk’, as it is referred to in some Mayan languages, is a term used to imply ‘creative force’ (Stuart 2010:289). Chaahk’s creative role is also suggested in a text from the Palenque Temple XIX Platform, which describes his involvement in the destruction of the world, decapitating the earth caiman and causing a flood that destroyed the old to make room for the creation of the new world (Stuart 2005:68, 180, 2006:101; García 2006:7). Consequently, although Chaahk acts as the destroyer of the old world, his destructive role eventuates in newness and beginnings. Chaahk was associated with falling rain, the downward chop of his axe and the rust of maize returning to feed the earth.

Correspondingly, Maya art frequently shows Chaahk in animated acts of destruction that lead to creation. The Maya understood that for something to live, something must die. Chaahk’s Postclassic name in the Popul Wuj, Thunderbolt Huracan, in its first Thunderbolt part refers to the merismus ‘time’ (see The Unseen in Maya Art) and in the second, Huracan, the swirling force of destruction (Christenson 2007:70, footnote 62).

J_Chaahk 5. Chaahk representation conveying movement in the Postclassic Dresden Codex: Details of a Chaahk triplet animate the deity to gradually raise his axe above his head. Animation extracted and adapted from www.famsi.org/mayawriting/codices/dresden.html, p. 32.

Chaahk’s association with one of the Thuderbolt Gods, that is Huracan, is further supported in Professor Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariego’s recent publication, Art and Myth of the Ancient Maya (2017:188-189). Here, Mazariego retells a story in which the Popoluca maize hero, Homshuk, setting off to look for his dead parents, journeys on the back of a turtle across the sea to the Land of Thunders, ‘where Hurricane was’ (Leandro Pérez’s version in George M. Foster 1945:193). Once arrived, he made music, which annoyed the Thunders, who summoned him. Homshuk was unsuccessful in convincing the Thunders (read Time Gods) to ‘turn back time’ and bring his father back to life; however, he eventually beat the Thunders in a series of contests, letting them live providing that they would sprinkle him with water when he got thirsty; that is, let it rain. In addition, Nahua stories surrounding rain making identify the Thunders as the ‘owners of water’; these promised to make water for the maize hero after he sacrificed a crocodile or caiman by cutting off its tongue to then make lightning with it (Mazariego 2017:189). The references to the rain-making abilities of the Thunders link Thunderbolt Huracan to the deity Chaahk, the rain maker, and the Thunders in general to time and sound (music).

Thunder-Lightning Merismus

The ‘Thunder-(lightning) bolt’ titles of the three Time Gods described in the Popul Wuj use a literary merismus expressing ‘time’. If the God of Birth is tied to lightning and the God of Death to thunder, then the God of Life and time remain in the middle, unseen.

Notably, ancient structures built in the flat Maya Lowlands are often hit by lightning; for example, in 1978, hitting and killing the unfortunate archaeologist Dennis Puleston, who was watching a thunder storm from atop the Castillo at Chichen Itza. It is possible that the Maya intended the great height of the temples to attract the energy of storms and act as lightning conductors, thus harnessing the creative energy embodied by the Time Gods.

Accordingly, the structures were conceptually and physically tied to the Maya thunder-lightening ‘time’ merismus. This means that the unseen space between the temples was just as important as the visible stone structures it separated; once again, connecting the metaphor of the day to the structure of three-part time and life.

| Moving from Temple of Birth to Temple of Life | unseen | ascent | ascending sun |

| Moving from Temple of Life to Temple of Death | unseen | demise | setting sun |

| Moving from Temple of Death to Temple of Birth | unseen | rebirth | dawn |